- Home

- international

- news

- Inside the Navajo Church Rock Nuclear Disaster, the largest radioactive disaster in US history that's somehow often forgotten

Inside the Navajo Church Rock Nuclear Disaster, the largest radioactive disaster in US history that's somehow often forgotten

James Pasley

- The 1979 Church Rock Nuclear Disaster is the largest radioactive accident in US history.

- 94 million gallons of radioactive water and 1,100 tons of uranium waste flooded out of a breached dam into the Rio Puerco.

In 1979, a dam holding millions of gallons of nuclear waste in Church Rock, New Mexico, collapsed.

In a matter of hours, 94 million gallons of radioactive water and 1,100 tons of uranium waste flooded into a nearby river.

The spill killed crops and cattle, and contaminated the surrounding land and the people who lived off it for decades to come.

It happened just four months after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. It was the largest accidental release of radioactivity in US history and third worst accident in history, after the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011.

Despite this, perhaps because it happened in a rural, low-income area, or perhaps because it was primarily people from the Navajo Nation who were impacted, it was largely ignored.

Here's what happened.

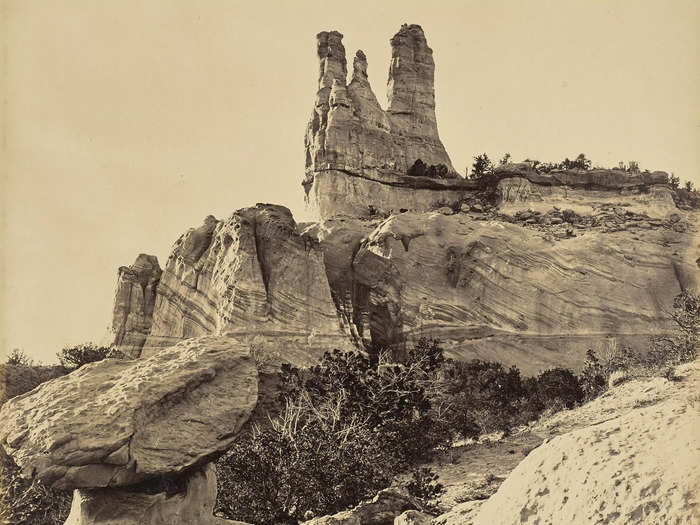

The Navajo Nation, which is the largest Native American territory, covers about 27,000 square miles across the boundaries of Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. Its people have lived in the region—known for its dusty, arid landscapes— for seven centuries.

Sources: Vice, Vox, Bureau of Land Management

Since the land was fairly inhospitable, the Navajo were mostly left alone in the 20th century. But that peace ended with the beginning of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race. Underneath the dry earth was one of the largest uranium deposits in the world.

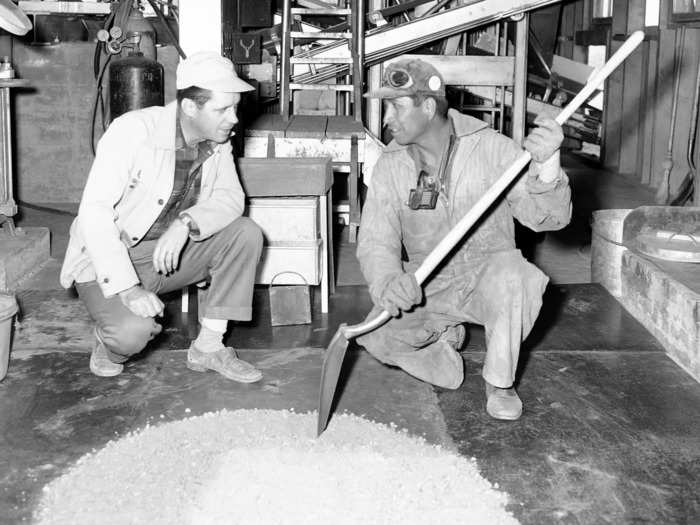

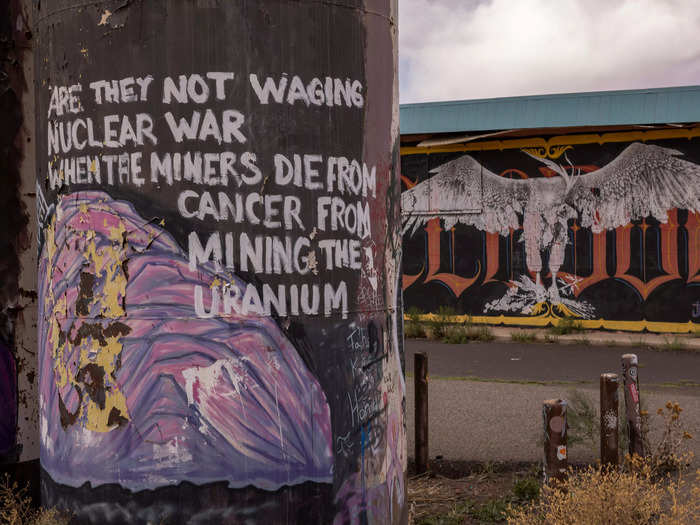

For about 40 years between 1944 and 1986, the federal government and private companies mined the area and often used Navajo people to do it.

Over that period, about 30 million tons of uranium were extracted.

Now, according to the EPA, there are about 500 abandoned waste piles, mines and mills across the region.

Sources: Environment and Society, Vox, VC Star, AJPH , Vice

Early on in this period, the government was happy to hire Navajo people to work in the mines, but it failed to warn them about the effects of radiation.

Sources: New York Times

Cattle drank from contaminated runoff, people built their homes out of lumber taken from uranium mines and children played in contaminated streams.

Sources: New York Times

That was bad enough, but in 1968 the United Nuclear Corporation (UNC) began extracting from the country's largest uranium mine, which was located in a small farming community called Church Rock.

Its extraction process required nuclear waste to be stored in dammed lakes called tailings ponds.

The dams were between 50-75 feet high and made of earth.

In 1977, two years before the accident, UNC already knew about large cracks in its dam.

But even though the officials were aware of them, they continued to overfill the tailing ponds.

A report later released by the Army Corps of Engineers found UNC made three key failures—it failed to use recommended materials during construction, it failed to report the cracks to regulators and it ignored advice from consulting engineers that could have stopped the disaster.

Sources: Environment and Society, Vox, VC Star, AJPH , Vice

It's not like nuclear accidents hadn't happened before. On March 28, 1979, a nuclear reactor on Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania had a partial meltdown that exposed 2 million people to nuclear radiation.

No one died, but about 140,000 people had to be evacuated.

CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite called it the "first step in a nuclear nightmare."

Sources: Environment and Society, Business Insider

Four months later, on July 16, 1979, UNC's dam failed. Out of a 20-foot wide breach, 94 million gallons of radioactive water and 1,100 tons of uranium waste flooded into the Rio Puerco.

One local named Larry King told Vice, "I remember the terrible odor and the yellowish color of the water."

The spill contaminated a stretch of river about 80 miles long, passing the homes of about 1,700 people.

Because the area was so dry, locals relied on the river for drinking water as well as for their crops and livestock.

Sources: New York Times, Environment and Society, Vice, Vox, American Indian Law Review, Science History, AJPH

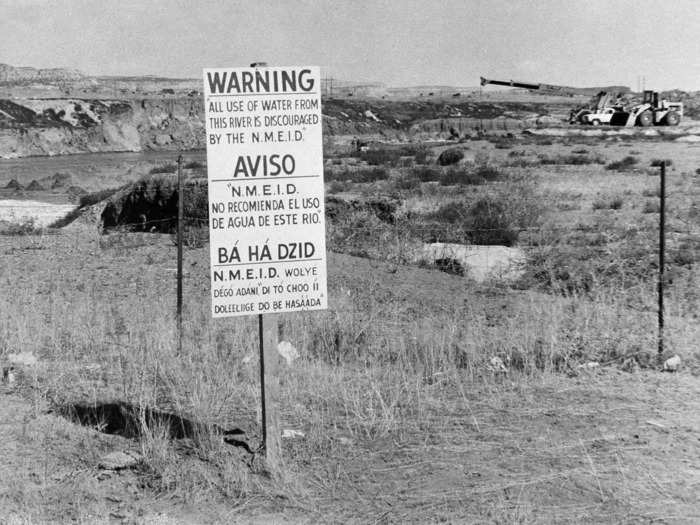

The spill caused crops to wither, contaminated sheep had to be killed and wells had to be closed off permanently. The water's radioactivity level near the dam reached 7,000 times the safe radiation limit for drinking water.

Blisters and sores reportedly appeared all over the feet of locals who walked in the water that day.

Sources: Vice, Vox, American Indian Law Review, VC Star, New Mexico History

The Church Rock spill was worse than Three Mile Island in terms of radiation. It released more than three times as much radiation. Yet while President Jimmy Carter visited Three Mile Island within days of the failure, Church Rock was basically ignored.

Newspapers described the region as "sparsely populated" and claimed there were no health hazards.

New Mexico's Governor Bruce King refused to declare that the region was a federal disaster area.

Sources: Vice, History.com, Science History, Vox, AJPH

Despite the local response, it was the third worst accidental release of nuclear radioactivity in the world, after the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986 and the Fukushima in 2011.

While UNC sent Navajo employees out after the spill to let people know the danger, it wasn't until a few days later that signs were erected and radio announcements made that warned locals not to drink from the river.

Sources: American Indian Law Review, AJPH

To make matters worse, after the spill no one was compensated, and the UNC only removed about 3,500 tons of sediment from the river—about 1% of the solid waste released in the spill.

Seven months later, a local newspaper reported that six Navajo locals who had been tested for radiation exposure had shown no acute effects.

By November 1979, the UNC had resumed operation at Church Rock. But instead of improving its practices, it discharged new waste into unlined ponds which led to intensive groundwater contamination.

In 1982, the UNC abandoned its Church Rock operation.

In 1983, due to the groundwater contamination, the operation was placed on the EPA's National Priorities List.

Yet that same year, federal and state authorities were still claiming the impacts the disaster had on people and the environment were minimal.

This wasn't the first time authorities had got it wrong about people dying from working in the domestic nuclear industry.

During the Cold War, hundreds of Native American miners died from cancer and lung diseases after working in the industry.

These deaths were scientifically linked to working with uranium, yet for years government agencies claimed no one had died or was harmed from working in the industry.

UNC also continued to dismiss claims of hardship from the Church Rock spill.

In 1983, despite locals noting their cattle kept dying after drinking from the water, Stanley Crout, a spokesperson for UNC, told the New York Times, "We just don't know of any substance to those claims."

Crout noted the reason the Navajos were concerned was because they didn't understand the effect of uranium.

Sources: New York Times, Vox, EPA, Science History, AJPH

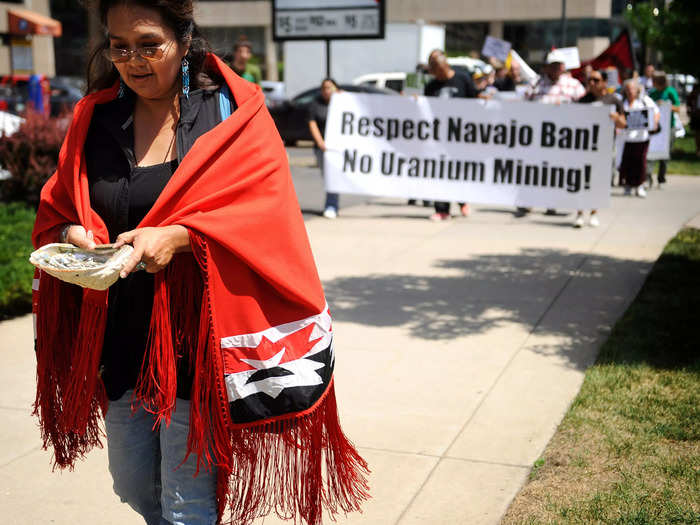

In 1990, the government officially apologized to the Navajo people. Two years later, UNC was ordered to invest $16 million to do a better clean up job, but instead the money was paid to its parent company.

Sources: New York Times

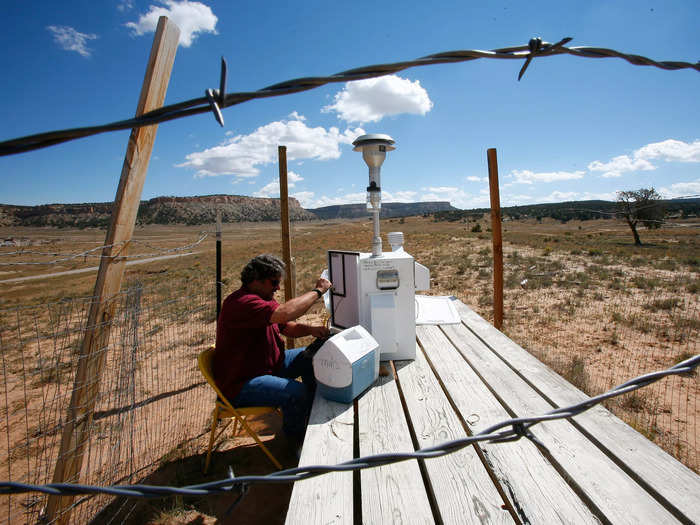

In 2007, 28 years after the accident, a local research group called Church Rock Uranium Mining Project found water sources were still contaminated from the spill.

Sources: Vice

Although a comprehensive study wasn't completed, a number of different studies noted people living in the Navajo nation nearby have had higher rates of birth defects, diseases and cancers.

Sources: Vox

From the 2000s on, the EPA slowly started cleaning up the area, including other mines and waste sites. By 2015, about $100 million was spent on the clean up—and about 200,000 tons of contamination were removed— but the pollution was far worse than the agencies first thought.

EPA Pacific Southwest regional administrator Jared Blumenfeld told the New York Times, "It is shocking — it's all over the reservation."

He said, "I think everyone, even the Navajos themselves, have been shocked about the number of mines that were both active and abandoned."

Sources: New York Times, Science History, AJPH

The repercussions of the spill and the mining are still felt today. As local resident Faith Baldwin told Vice in 2019, "Our generation is afraid of having children."

She said, "Cancer runs in our family but it shouldn't. Cancer, diabetes were non-existent in Navajo rez."

Sources: Vice

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement