- Home

- international

- news

- How flash photography put a spotlight on New York's rampant poverty in the late 1800s, catalyzing the demolition of the city's biggest slums

How flash photography put a spotlight on New York's rampant poverty in the late 1800s, catalyzing the demolition of the city's biggest slums

James Pasley

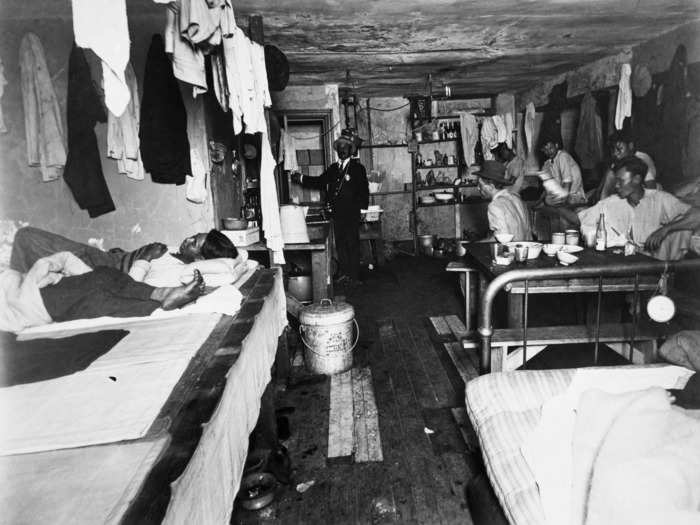

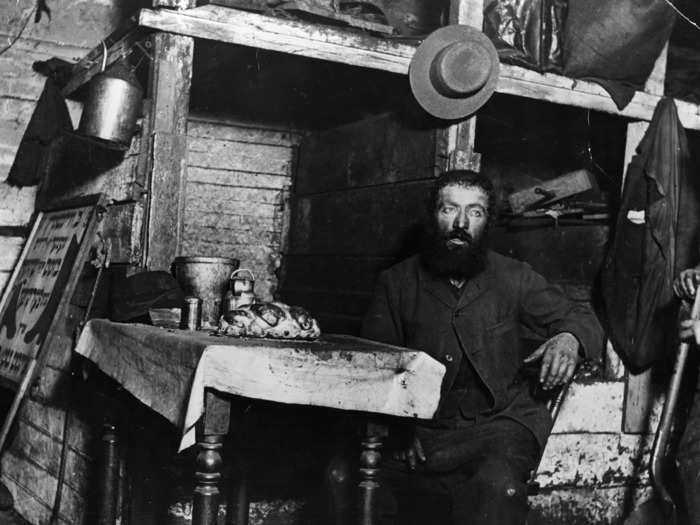

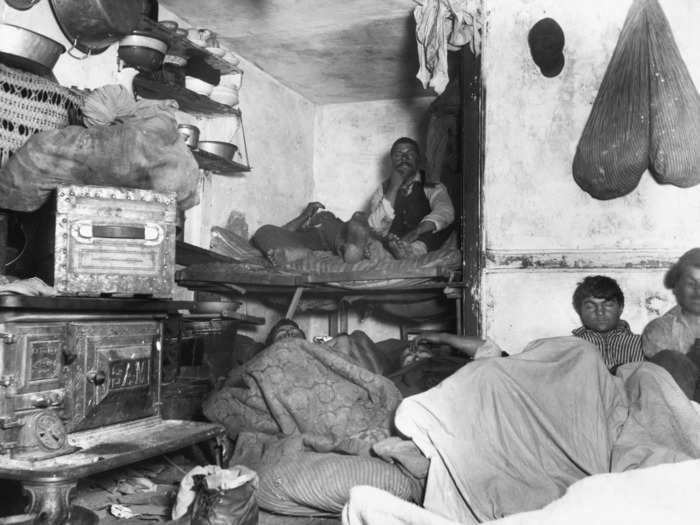

- Danish photographer Jacob Riis captured the inhumane conditions of New York's slums in his book, "How the Other Half Lives."

- He documented the poverty previously hidden in darkness using a magnesium powder to produce a flash.

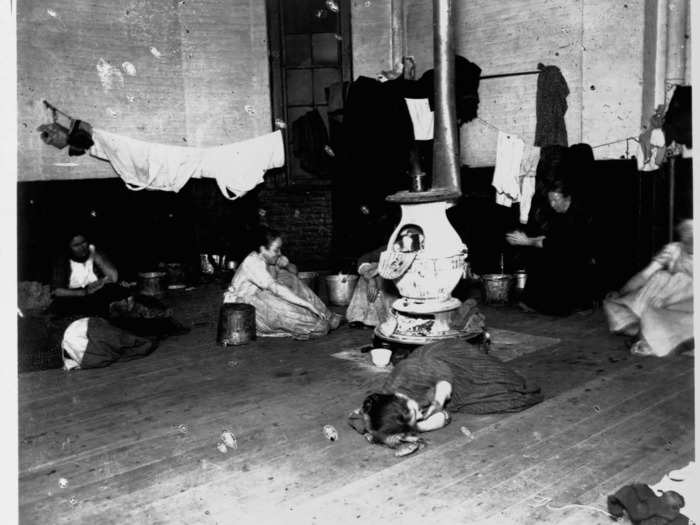

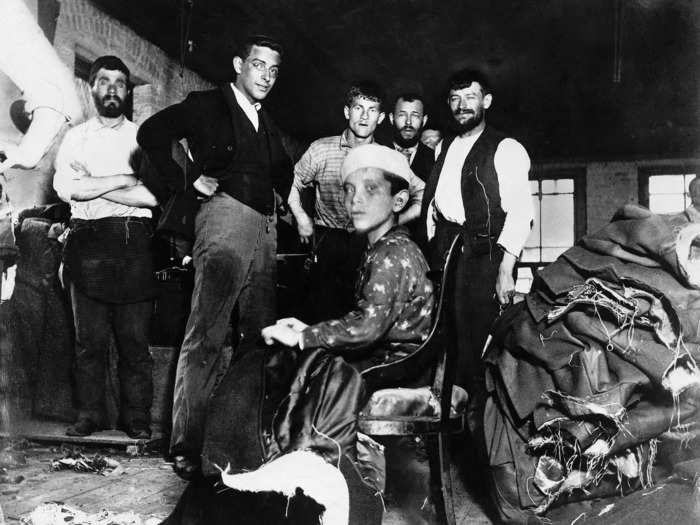

In the 19th century, New York City was filled with more than 1 million immigrants living in poverty.

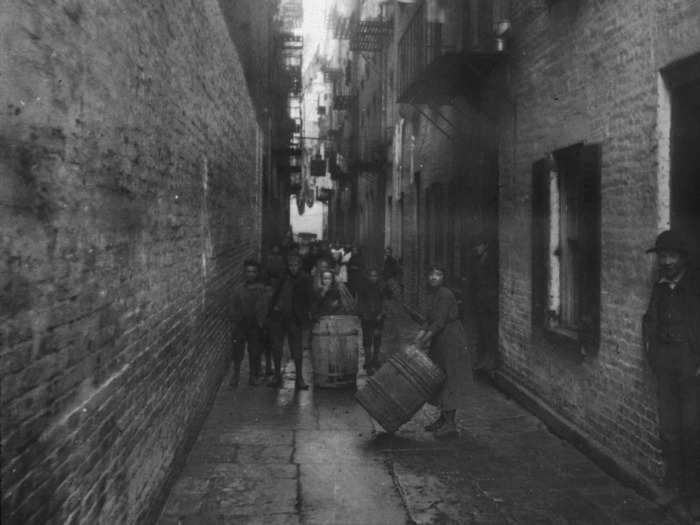

Despite the vast number, they were easy to ignore because they lived in windowless tenements and the underbelly committed crimes down dark alleys.

But the world caught on when Jacob August Riis, a Danish journalist and photographer, started documenting poverty using a recently invented flash magnesium powder. He later released a photojournalism book, "How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York." The book raised awareness about poverty in New York and prompted officials to take action.

Here are some of the photos that changed New York City — and America — forever.

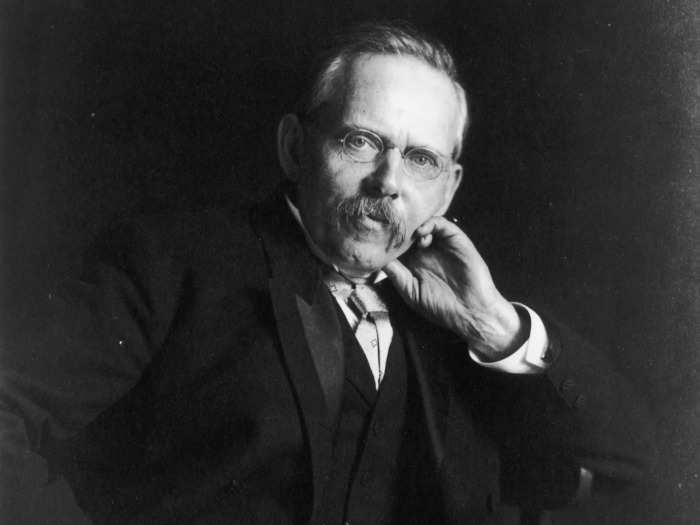

In 1870, Jacob August Riis, a 21-year-old man from Denmark, moved to New York City after a girl rejected his marriage proposal.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, NPR

Riis was the son of a school teacher and didn't come from money. When he arrived in New York, he had $40 to his name. He worked as a carpenter before losing his job and becoming unemployed in 1873.

Source: NPR

Riis experienced what it was like to have nowhere to live and no money to spend. This would prove crucial later on when he was documenting others because he understood what it was like.

Source: NPR

By 1877, Riis had a wife and a place to live in Brooklyn, and he'd landed a job at the New York Tribune as a police reporter. There, he wrote about the poor underbelly of New York City.

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, New York Times

He wanted everyone to know that while Fifth Avenue was lined with mansions and a select few lived in absolute wealth, more than 1 million people — three-quarters of the city as a whole — struggled to feed themselves and stay healthy in a city plagued with diseases.

Source: New York Times

But writing about the issue wasn't enough. He wanted to show the city what was going on. To do so, he began to take photographs. He took his first in 1888.

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, New York Times

On nightly rounds across the city accompanied by two assistants and a policeman, Riis took his camera and newly developed magnesium powder, which created a flash, often shocking people.

Though revolutionary, the flash also caused at least three fires.

Sources: NPR, Washington Post, New York Times

What happened next changed New York. Bonnie Yochelson, a former curator of the Museum of the City of New York who cowrote, "Rediscovering Jacob Riis," wrote that he had "captured what had never been before seen in a photograph."

Source: New York Times

Before, it was easy to avert the eyes because the city's poverty was hidden down dark alleys and in windowless tenements — but that changed with the flash.

Sources: New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine

At first, Riis solely showed his photographs in lectures and published in Scribner’s Magazine. Historian Daniel Czitrom, who co-wrote “Rediscovering Jacob Riis,” called Riis the first muckraker.

Source: NPR

In 1890, he published his most famous work, a photojournalism book titled, "How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York," a collection of his photos and writings about New York's poor.

He had ordered it by neighborhood and ethnic groups. He believed that ethnic groups were distinct. His writing in the book has been criticized for playing into stereotypes and for its racist undertones.

According to The New York Times, in the book, he is critical of Italians, Irish, Jews, and the Chinese.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, NPR, New York Times

Regardless, the book was a bestseller. Along with the photos, it included facts about the state of New York — like how 12 adults would sleep in tiny rooms less than 15 feet wide, or that the infant mortality rate was 10%.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, History.com

Riis harnessed contrast in framing his photos. Here, he portrayed the purity of childhood belief against the bleak space where it was practiced.

He documented opium dens and basements. This is a photo of an area of New York City called Bandits' Roost.

Source: New York Times

His photos captured crime, child labor, and terrible living conditions, including this man who lived in the trash beneath a dump. He wanted to shock people into action.

Source: New York Times

But Riis was far from perfect. Yochelson told The New York Times that he "was a state-of-the-art, media-savvy journalist, but in his sentimentality and in appealing to the Christian conscience, he was a creature of the Victorian, rather than the Progressive, era."

Source: New York Times

He believed a defective character led to being poor, and although he showed the world how they lived, he never gave them a chance to speak for themselves.

Source: New York Times

In 1894, his work prompted action from then-New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who said to him: "I have read your book, and I have come to help."

Sources: Theodore Roosevelt, The Citizen

Roosevelt ended up closing down some of the worst slums in New York and described Riis as the city's "most useful citizen."

Source: CBS News

Despite the monumental impact of his work Riis didn't stick with photography and stopped taking photos by 1892. In fact, he never even considered himself a photographer.

"I am no good at all as a photographer," he wrote in his autobiography published in 1901.

After his death in 1914, his negatives were left boxed up in an attic for 30 years. It wasn't until a photographer tracked them down in the 1940s that 415 negatives were found.

Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, New York Times

Czitrom told The New York Times that no one reads his work anymore, but his photos are still relevant to this day. They act as a harrowing reminder of how hard life was for the poor in New York City — and how far things have come.

Source: New York Times

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement