- Home

- international

- news

- Famed photographer Dorothea Lange's images of Japanese internment during WWII was censored by the US government that also hired her to document it in the first place

Famed photographer Dorothea Lange's images of Japanese internment during WWII was censored by the US government that also hired her to document it in the first place

Isaiah Reynolds

- Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US instated relocation camps for all Americans of Japanese descent.

- Photographer Dorothea Lange was hired by the government to document the camps, but her archives were later impounded.

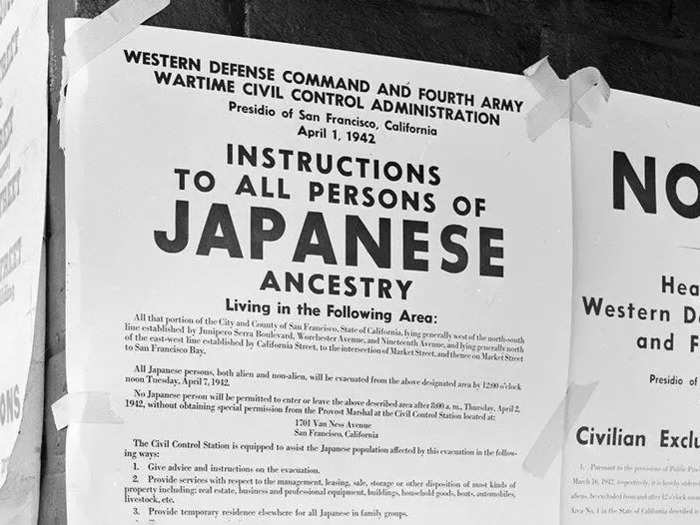

In February 1942, three months after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order authorizing "the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security," allowing Japanese Americans, citizens or not, to be moved to "relocation centers."

For the next three years, 120,000 Japanese Americans were placed in concentration camps in the American West. The newly-minted War Relocation Authority (WRA) was responsible for handling all matters of internment — even public relations.

Source: Vox

The WRA hired photographers, notably Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, to document the camps for the public.

Lange was well-known for her work during the Great Depression, most famously capturing the image titled "Migrant Mother."

Source: MoMA Learning

Lange's photographs, however, were withheld from the public for the duration of the war and not widely circulated like Adams' were. While in the camps, Lange was not allowed to "photograph the wire fences, the watchtowers with searchlights, the armed guards or any sign of resistance."

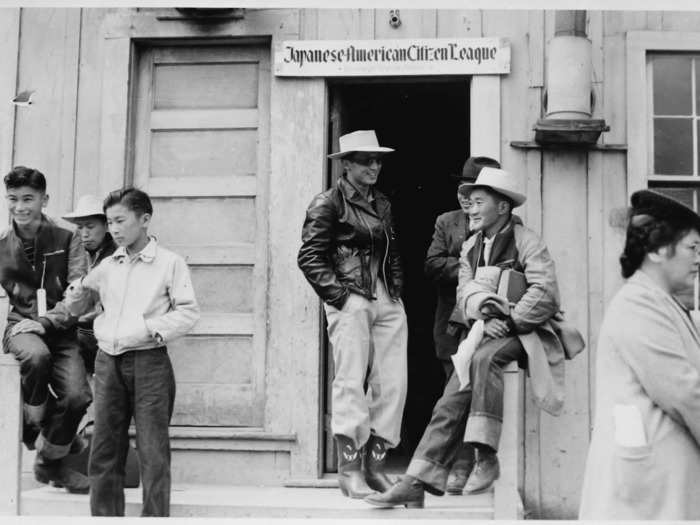

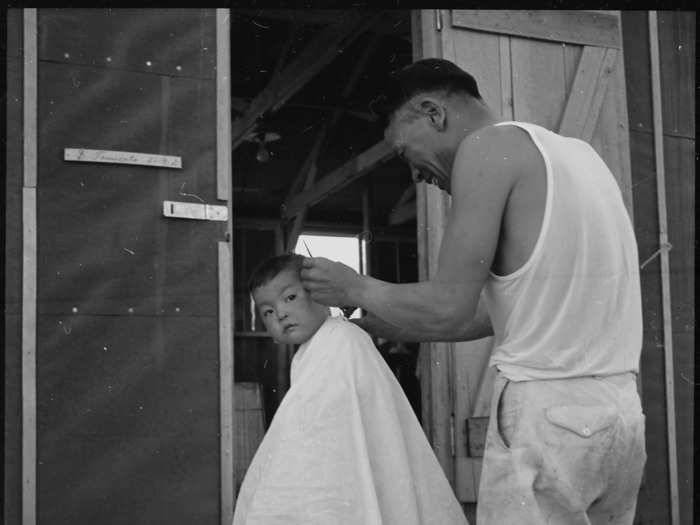

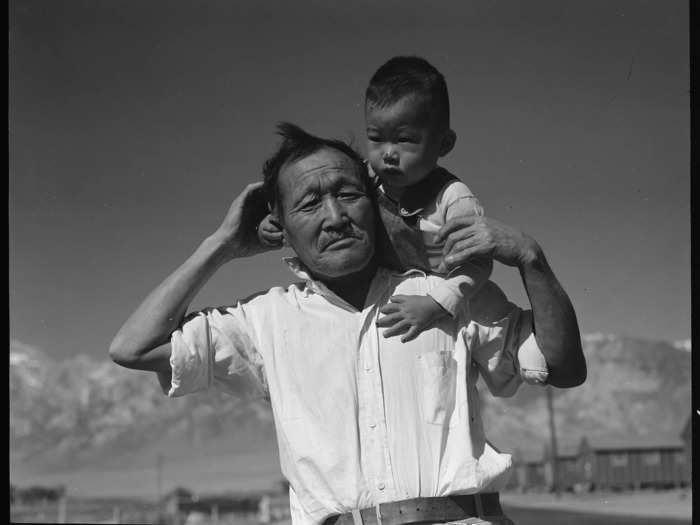

Despite limitations, Lange's documentary-style photography captured an otherwise unseen aspect of their forced incarceration.

Source: New York Times

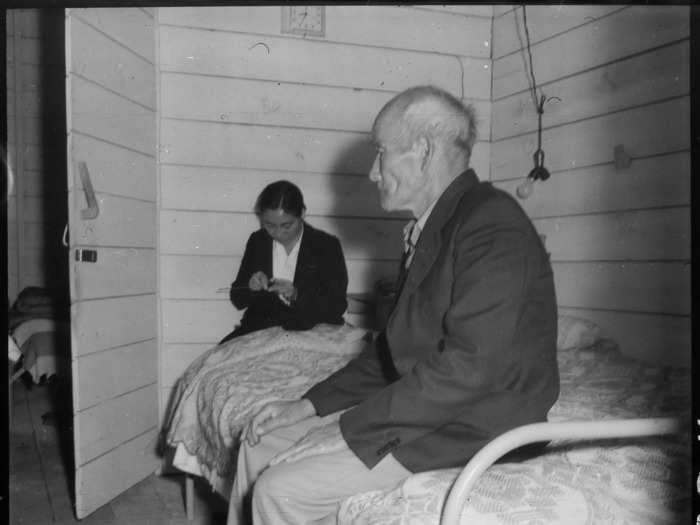

Contrasting Adams' imagery, Lange captured the stark reality of life in the internment camps — long lines for meals, inadequate resources for children's education, and questionable living standards in renovated horse stables.

Source: National Archives

Lange's images have been lauded for capturing the uncertainty and anxiety of the subjects in the lead-up to evacuation.

Source: Los Angeles Times

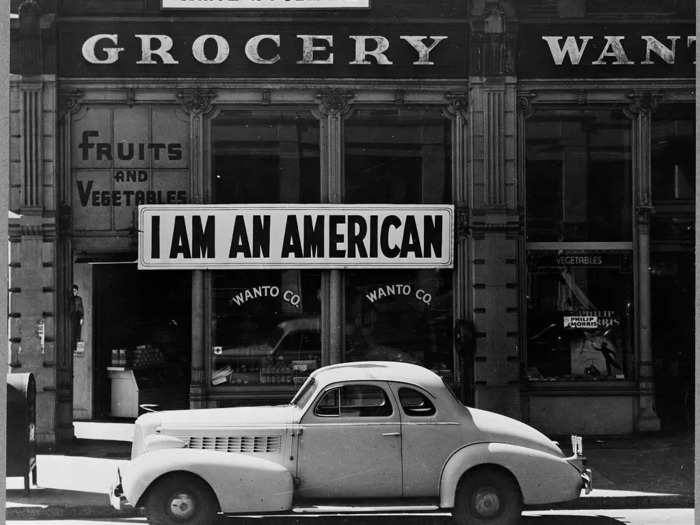

Hundreds of harrowing images show Japanese Americans removing their belongings from their homes, closing their family businesses, and preparing for a future of complete uncertainty.

During this time, nearly two-thirds of Japanese Americans forced into internment were American citizens.

However, some in the media argued their ties to Japan overpowered their American identity.

"A viper is a viper wherever the egg is hatched..." a column in the Los Angeles Times read in 1942. "So a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents… grows up to be a Japanese, not an American… and is himself a potential and menacing, if not an actual, danger to our country unless properly supervised."

Source: Los Angeles Times

Ultimately, Lange's images were impounded by the WRA for the duration of the war and were not widely accessible until the early 1970s, nearly 30 years after they were taken.

Source: Vox

The internment lasted another three years. In 1943, the government had even established a military combat unit for WWII comprised of Japanese internees in relocation camps.

Source: United States National Archives

After the war ended in 1945 and internment camps shuttered, many Japanese Americans were left scrambling. They had no homes to return to and were unfamiliar with the terrain surrounding the relocation camps.

Source: United States National Archives

The unearthed photographs from Lange's account were used for the movement demanding justice for Japanese Americans through the 1970s and 80s.

In 1988, then-President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, formally recognizing the injustice of internment and providing a $20,000 cash payment in reparations for every individual forcibly incarcerated.

Source: Vox, United States National Archives

In 2006, a book collection of Lange's wide portfolio of Japanese American internment was published under the title, "Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment."

Linda Gordon, a historian at New York University who edited the book, maintained that the temporary suppression of Lange's photography was not by happenstance.

"The photographs were impounded because they were unmistakably critical," she wrote in the Asia-Pacific Journal. "They unequivocally denounced, visually, an unjustified, unnecessary, and racist policy."

Source: Asia-Pacific Journal

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement