This January, noted blogger

This January, noted blogger

Sullivan initially set a revenue goal of $900,000 a year to maintain the standard of the blog. He specifically set out to reach his revenue goal without the help of any advertising revenue, saying “it provides a vital revenue stream for almost all media products. But we know from your emails how distracting and intrusive it can be; and how it often slows down the page painfully.”

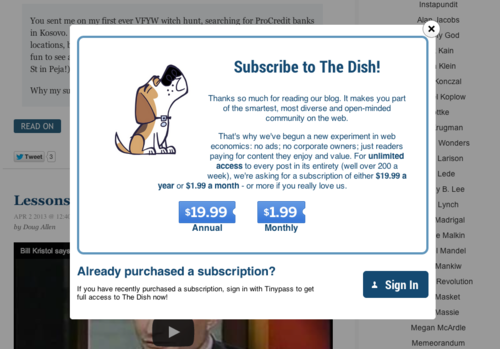

Sullivan also declined to take any venture capital. He threw himself entirely at the mercy of his loyal and sizable readership, outlining the core principle: “we want to create a place where readers – and readers alone – sustain the site.” He asked readers to sign up for annual subscription that costs a minimum of $19.99, and gave the readers the choice of paying more if they wanted.

The Dish’s financial performance is being closely watched, as is every high-profile effort to monetize digital content these days. Luckily, for those interested, Sullivan has made the performance of his paywall entirely transparent.

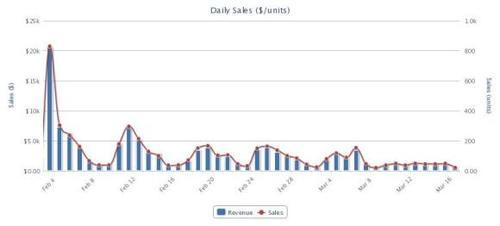

So, how’s he doing? Well, Sullivan got off to a booming start. He raised over $333,000 from 12,000 subscribers in the first 24 hours his new blog went live, leaving him “gobsmacked.”

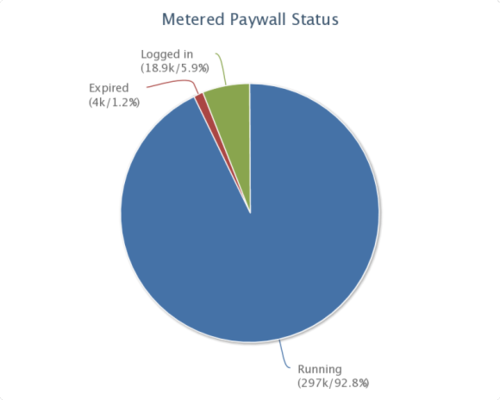

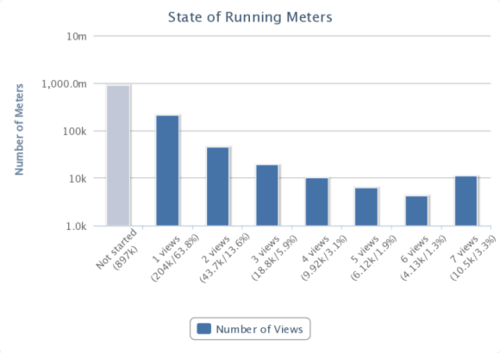

While subscriptions have continued to come in, the initial burst has gradually turned into a more consistent trickle (or as Sullivan puts it, they’ve “flat-lined.”) As of March 12th, The Dish had collected over $660,000 from nearly 25,000 subscribers. Sullivan has both tightened the meter and introduced a new monthly subscription option (a $1.99 “app-like fee”) in an effort to bump subscriptions in the last few weeks.

A few months in, it’s very clear that when it comes to the viability of Sullivan’s experiment, things are still very unclear. So, we decided to sit down with Sullivan to get his take on the performance of his model so far. We discussed how and why he launched the meter, analyzed what he’s learned since the launch, and talked about his future ambitions for the The Dish and digital journalism in general.

The full interview is below (all bolds are our own).

BI: You’ve been doing a lot of interviews like this recently, talking more about the business of your blog than the articles and opinions within it. Do you find yourself doing more of these than you’d like?

AS: “Yes [laughs]… but that’s really not been the main struggle. It’s been incredibly grueling because we had a quick period of time to completely transform what we were doing. We’re all journalists, not business people. We had to figure this all out ourselves in a space of a month. We had to figure out a meter, how to set up a company, how to set up an LLC. At the same time you’re writing every day and trying in a very competitive marketplace, and asking people for money, to put out the best editorial content you can.

When I was at other

BI: So, what was the impetus for leaving The Daily Beast?

AS: Well, the contract was up and we had to figure out what to do. And it’s interesting. Each time we’ve [entered into an agreement with a larger media company] over the last 13 years, the media landscape has changed completely. You make a deal for two years and the assumptions you made completely changed.

Editorially and organically it felt like it was itself. And the advertising and CPM-based model was clearly softening. The concept that you could support online journalism like you could print journalism with ads… began to disappear. So, the only revenue we had [at The Daily Beast], I thought, wasn’t going to go anywhere. I sure as hell wasn’t going to gamble with sponsored content. I couldn’t do that.

BI: How did the decision to take The Dish independent with a meter come about then?

AS: We had a blue-sky sit down dinner [and we asked ourselves]: “What are we trying to do with this? Where we asked what are we trying to get from this? What’s the value in it for us?” And then we went to a discussion of revenues.

What’s the most valuable thing we had to sell? It was the connection we’ve had with a readership that’s been with us for a long time. It’s an incredible bond. Most big websites are trying to trap the migrating flocks of Internet readers, and some are figuring out how to do that technologically better than others. But that was never going to work for us. That’s not what we were.

So, we thought of the subscription idea, the meter idea…. Because we had no clue whatsoever what the response would be, we decided to start and see if we can do it with that alone.

So, we thought of the subscription idea, the meter idea…. Because we had no clue whatsoever what the response would be, we decided to start and see if we can do it with that alone.

BI: How do you wrap your head around the meter concept?

AS: Back in the day I would go to the Harvard Square bookstore. When I was there in 1984, having left England, there was no way for me to know what was going on back home except in the British papers. I would go there and flip through the newspapers. At some point the dude had every right to say “Either buy the magazine or put it down.” That’s basically what the meter is. At some point, the store owner says to you “Thanks for coming in, but either buy something, or leave.”

BI: What were some of the other key decisions you made at launch?

There were a couple of eight-minute decisions. Literally the night before, I said “Why don’t we leave the $19.99 field blank so they can have an option of paying what they want?” That has earned us an extra $100,000 so far.

Another decision was to be totally transparent. Lets show our readership exactly how much we’ve got and continue. So if we have to make tweaks, like we just did, [they’ll understand why].

BI: How do you feel about your new job responsibilities, being responsible for both editorial and business considerations for the first time?

AS: I never wanted to be a businessman. I tried to avoid it. But, whether I liked it or not, it’s a business. Either someone else was going to get the profits, or I was. Also, the people working with me deserve a share in the profit, which is why two people [Executive Editors Patrick Appel and Chris Bodenner] with me now have equity. I wanted to incentivize that kind of work ethic.

BI: At launch, you indicated that you’d need $900,000 in annual revenue to keep The Dish afloat. That number, for better or worse, has become the barometer by which your experiment is to be deemed a success or a failure. So, I wanted to dig into that number a bit more. What exactly does it include?

AS: It’s a conservative estimate. In our first year plans, our budget, when we mapped out how much all of this would cost – suddenly providing health care for eight people, legal fees, server costs, do the Ask Andrew Anything videos, studio to rent – it all adds up. It is those costs – and then because there are three of us who do the lion share of work - aren’t on salary. We will live off of the profits if there are any.

The idea is not to get Andrew Sullivan to work for free. That’s what I’m doing right now. I’m working my guts out every day at a point in my career when I should be settled down, and I have no money coming in at all, except for my column in London. And I have to pay my rent here.

BI: Speaking of your move to New York, which you have documented in some detail, why did you decide to do it when you took The Dish independent?

I moved to New York to figure out how all this works… to discover that no one knows.

BI: Has your approach as a writer and editor changed as a result of your newfound business responsibilities?

AS: I think things have shifted a little bit. One likes to think one is above all this and say “I’m a writer, I only produce what comes from the purist of my intentions and none of this affects me.” And, it doesn’t really affect me. I’m not going to change my views on a subject because it’s more popular. I’m not going to stop writing about circumcision even though readers roll their eyes when I do. I’m not going to stop shitting on New York, simply because it's hilarious to do so. None of that will change.

But I found that there had previously been a subtle incentive to create pageviews…. Our incentive now is to get the guy or the woman who read it today to subscribe and get the guy or woman who subscribed yesterday to re-subscribe in a year's time. That’s what we need. We need to make the experience worth what they’re paying for it and worth renewing.

BI: And how do you go about figuring out how to do that – creating an experience worth paying for and worth renewing?

BI: And how do you go about figuring out how to do that – creating an experience worth paying for and worth renewing?

AS: What happens in this process, since the first post I put up, this medium kind of tells you where to go. You just need to listen to it. Stats help, so do reader letters…. You try things, if they work great, if not, you let it go.

Three years ago, when it wasn’t in our interest, we installed the “Read On” button and our pageviews were halved. We made a decision that the reader experience was more important than the

The surprise is being there first and establishing that consistency and building that audience that’s sticky, it works online. The thing is you have to deliver every day. If you do not give them their drugs, they’re going to fucking kill you. It’s addictive.

The horrible thing is – it’s as addictive for me to produce as it is for them to consume… My social life has collapsed. It’s my blog, my husband, and Breaking Bad at this point. And that’s not good for me.

BI: So, what is the most addictive stuff for The Dish subscribers? What’s the stuff they’re paying to read?

AS: Well, for example, we found the posts where people clicked on “Read On,” hit their limit and were most likely to say “OK, I’ll subscribe” turned out to be my long pieces. And that was a surprise.

That signaled to me part of what readers of The Dish want is more of my own writing - which is truly flattering and very intimidating. But I don’t think I’d have the audience for those pieces had I not generated the other content and features that were daily.

They have also voted consistently not to have a comments section. That tells me about our readership and what they want. They’ve been guiding me.

BI: Do you feel the need to enhance your product offering now that The Dish is a subscription product? Are there other things you’d like to do now that you are independent?

AS: Of course, only a few months in, there’s a bunch of ideas I'd like to develop. I’d love to commission long-form journalism. I want to reinvent the magazine online, to have it be both what you read at work as a distraction and for fun, but in the same community of thought, commission a long-form writer to nail a 10,000-word piece on a subject that’s within our area of discourse.

When you edit a long-form magazine, part of what you focus on is what Tina Brown calls “the mix.” You want some short pieces, some long ones, some funny ones, and some serious ones. You need the reader to enter it and enjoy it at any level of focus. You want to capture the full range of experience. What magazine editing is all about is letting readers trust editors to pick something worth reading. That’s what magazine writing is all about. If we do it, we have to make sure it’s done really well.

BI: Why do you think that’s the natural move for The Dish?

BI: Why do you think that’s the natural move for The Dish?

AS: What emerged out of what I did as a single blogger is a very clear voice in this space. From that, we developed little magazine features – quote of the day, etc. So other people can share that sensibility and mind meld with you. That is building out a magazine from a blog. The next natural stage is to commission the long-form journalism.

Let’s say in a fantasy world we got a Steve Brill. We’ll pay him $10,000 - we’re not going to go the slave labor route… At that point, why are we not a magazine? We got everything else. Now we have the cover story. Except you don’t get it once a week in one big package stapled together, you get it whenever you want, in any format you want, and people who don’t buy it can browse it.

BI: How does this talk to who your audience is and how they consume The Dish?

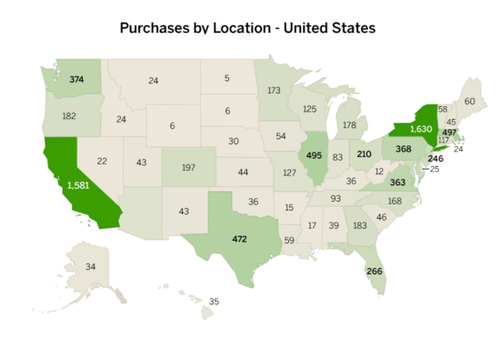

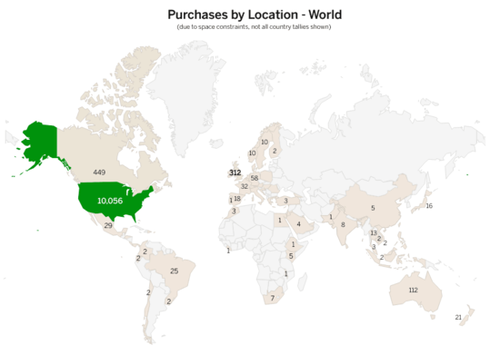

AS: We have not conquered the weekend. We are a workplace product. We exist for bored lawyers. We are the lunchtime break. The late afternoon goofy video guys. And we intuitively follow where our readers are. I post things I want to hit at peak usage hours.

But, as we’ve grown, the lunchtime peak has become much more a plateau. You have to start from where you are, figure out the virtues of where you are, and evolve accordingly. But it’s a constant evolution.

BI: Are there other things besides long-form journalism you’d like to try?

AS: We haven’t tried too much. We never really went into TV. I just didn’t think we can do it well, I thought it was crass. In general, TV is better on TV. If we do video at some point [besides the Ask Andrew Anything], along with long-form journalism, and podcasts, we have to do it really, really well.

My goal now is to make the experience of having subscribed feel good. So it also means writing more and more stuff that’s not available to anybody else, or giving them a free podcast where everyone else has to pay.

BI: What’s stopping you from doing any of this right now?

BI: What’s stopping you from doing any of this right now?

AS: Right now we don’t have the human power to do it. Putting out 50 posts a day and have them not be stupid when there’s so much else for people to look at is not easy. It’s much harder than it looks. Three of us have worked together every day for five years now [to get where we are]. We’re very lean.

We have a little motto, from a Shepard Fairey picture of Darwin, with the phrase “very gradual change you can believe in.” We are very committed to slow evolution. But we’re having a debate now. Do we go big now? Do we wait for a year until we stabilize? Or is that actually taking a risk? Do we go for long-form journalism now? Do I give more of my savings to make the reader experience better and make them more likely to renew as well as generating some more analytical science?

The trouble is you do need a real a magazine editor to do that for us. There are limits on the human mind and body. I’ve always said if someone ever dies from blogging, I’ll be the first one. It’s a hard time turning it off because consumers never turn it off.

BI: Back to the $900,000 number. There’s a lot you want to do and cash is tight right now. Advertising dollars could help with that. However, you've seemed pretty dead set on making this a pure subscription play. Is there a scenario where you would consider advertising, as you could control the who, what, and how of it?

In my first post after we launched, I said I could be open to it down the road. So, I don’t think I’ve boxed myself in at all.

I just think people personally value, increasingly online, a higher signal to noise ratio and they may pay for a premium, ad-free, disruption-free process, where they don’t even have to click for an unfolded post, and instead have an infinite scroll, that experience of a completely annoyance-free community. Gutting the normal webpage of comments and ads, that’s a gamble on a certain kind of model.

What we have to prove first is that we can do what already do within a budget we can afford.

BI: And what about venture capital?

AS: I’m a little nervous about venture capital. I’ve seen too many people aim big and fall flat on their faces. The only other thing about venture capital… The Dish exists to say things other people don’t want to say and doesn’t have to ask anybody’s permission.

Whether you like it or not, even if you have the best venture capitalists, if I say or stand for something they don’t like, they’ll always be more pressure on me. More pressure than even at The Atlantic or Daily Beast. There, in my contracts I had inviolate editorial independence, much to the internal excruciation of David Bradley. There’s nothing he could do about it, nor would he try to. But [with venture capitalists], you can see how the pressure to conform would creep in.

BI: Is there a red line you won't cross in your push to sustainability and profitability?

BI: Is there a red line you won't cross in your push to sustainability and profitability?

AS: Advertising and venture capital are perfectly possible if we have to. But, I like the idea of remaining as pure as possible. I understand at some point we’ll have to make a decision about that and our ambitions. Or, maybe not.

The line is I will not do sponsored content or native advertising. I will not blur what is advertising and what is editorial. I will always provide The Dish in an ad-free form for someone, for a core readership, at a certain price. That is forever.

I think the alternative is people seeking editing they can trust, and the only way they can trust it is because it's transparent as possible, it corrects itself prominently when wrong, holds itself accountable, airs dissent within it, and [optimally] it relies entirely upon its readership for its survival.

BI: It seems as if your experiment is also about demonstrating an ability to sustain what you consider to be old-school journalism in an increasingly digital world. Do you think the success you’ve had, and the lessons you've learned so far, are transferable to other journalists or blogs? If so, how?

AS: I absolutely think it’s transferable. Tinypass is a very easy thing to put on a site, and people can pay whatever they want. It may be that it’s not your day job, but it still adds up… At this point the role of the journalist has becomes less “I am absorbing all this information for you, then figuring it out all my self and then writing it up,” and more “This dude has the right thing, I’ve read it, here’s the key parts, check it out yourself, put it up in real time.” It’s more like a disc jockey remix of current events and opinions.

BI: How much would you pay for The Dish? How much do you think its worth? I ask because it's very conceivable that, at some point, you may need to raise subscription prices on existing subscribers to hit your desired revenue goal.

AS: [Laughs] I pay $50 to Talking Points Memo so that will tell you something… I think its worth it. I’d happily pay $50 a year and I can prove that I did. And I asked readers to do so.

I am too falsely modest to say how much I’d pay for The Dish and way too close to even understand the concept. It’s very hard for me to see The Dish as some option for me to read. I, generally speaking, hate everything I write and say its all crap. But, every now and then I go on vacation and I look at it and read it. And I go “that’s not bad, is it?” If I was a general reader and wanted to find out about the world, it’s pretty comprehensive and kind of fun.

BI: What happens if The Dish doesn't hit the $900,000 revenue number? Is there a conceivable way where it simply ceases to exist?

AS: We can still end up surviving as long as I don’t take a salary at all. We could survive if I don’t mind losing my savings. We’ll survive, we’ll figure it out by whatever means we do. We’re going to make this work. But we’re deliberately trying to put this pure model through the ringer so that we’re forced to do other things if we need to.

AS: We can still end up surviving as long as I don’t take a salary at all. We could survive if I don’t mind losing my savings. We’ll survive, we’ll figure it out by whatever means we do. We’re going to make this work. But we’re deliberately trying to put this pure model through the ringer so that we’re forced to do other things if we need to.

Chris and Patrick are living on no salary at all and they’re in their 20’s living in Brooklyn. They need to have something in their bank accounts, and they’re working incredibly hard. Their salaries come first.

I don’t mind taking a big pay cut for a while, but not indefinitely. I do this for a living. You’re not asking anyone else to do this for free.

BI: How would you like people to think of this experiment? What should the expectations be? What is a success?

I don’t see you why you can't see it as your neighborhood business, a Brooklyn artisanal shop that makes money but is never more than it is.

But, I've constantly underestimated this blog and what it will make me do.