- Home

- slideshows

- indiainsider

- Anti fake news laws around the world

Anti fake news laws around the world

Singapore

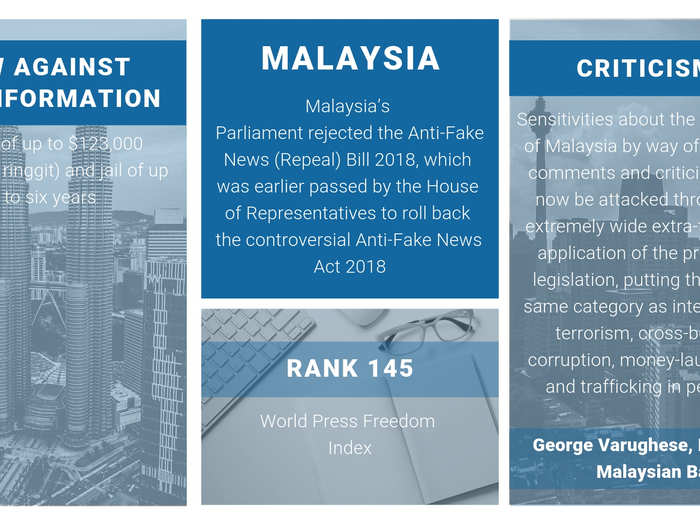

Malaysia

The law against fake news in Malaysia, a constitutional monarchy, was implemented ahead of its general election in 2014 under Najib Nazak, the country’s former prime minister. The controversial law was criticized for being repressive and Nazak was accused of using it to filter free speech when publications criticised his government of mismanagement.

Mahathir Mohamad, the current Malaysian prime minister, promised to scrap the law and while the Repeal Bill passed in the House of Representatives, the Senate rejected it in September last year.

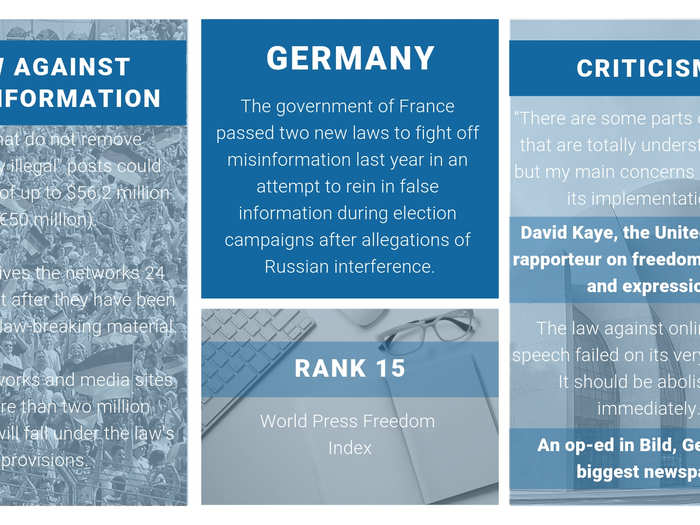

Germany

The German Parliament passed the Network Enforcement Act, commonly referred to as the NetzDG, in 2017. According to media reports, the German government is currently working on improving the law after criticism that too much online content is being blocked.

The effort of the German government was to ensure that Germany’s stand against hate speech, including pro-Nazi ideology, was enforced online. But, the Human Rights Watch (HRW) has said that the law isn’t the correct way to combat the spread of misinformation, criticizing it for setting "a dangerous precedent for other governments looking to restrict speech online by forcing companies to censor on the government’s behalf."

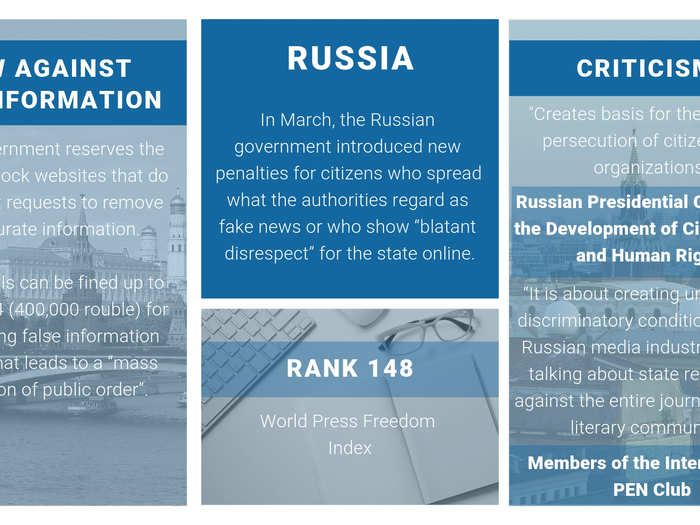

Russia

Russia’s new laws against fake news were signed off on by the country’s President, Vladimir Putin, in January earlier this year. Journalists, human rights activists and even the Kremlin’s own departments have heavily criticised the law for propagating fear.

The government has defended its stance stating the the laws "ensure protection against so-called web-based terrorists." Russia is also one of the worst countries for press freedom, and notorious for jailing even rock musicians who criticise the government.

France

As a liberal democracy, France’s anti-fake news law has a different story than the others. Rather than the primary criticism of the law being that its curbing freedom of speech, it seems to be the fact that its targeted at foreign publications, specifically the Russian press.

One of the publications, RT, claims that the French President, Emmanuel Macron, harbors a grudge against certain Russian media outlets. He allegedly referred to RT and Sputnik as ‘propaganda’ feeds and has kept Russian journalists from access to be working visits.

While putting laws in place might be a deterrent for the spread of misinformation, there’s still a lot that falls in the grey area and what amounts to censorship.

For instance, when reporting a fake news post on WhatsApp, does the person spreading the news face trouble or the creator? And, with end-to-end encryption that supposedly keeps messages from being read — even by the companies in charge — how does one track down the original sender?

Many tech giants, while conceding to government demands for more checks, have previously been staunchly against efforts to censor speech, especially in authoritarian countries like China. Google famously pulled out of China in 2010, citing censorship issues.

Then there’s the question of defining ‘fake news’ because, on the one hand, there’s actual misinformation and, on the other, there are legitimate news articles that are shared on social media channels that can be flagged as ‘anti-national’ posts or fake news, inviting potential punishment.

While the US has one of the most liberal laws against any form of government censorship, Donald Trump, the President of the United States, has often publicly labelled credible news outlets like CNN, the Washington Post and the New York Times as publishers of fake news, and declared that ‘the press the enemy of the people.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement