Representative image. BCCL

Authored by: Akshita SharmaIndia’s growing economy has witnessed an ever-declining female labour force participation (FLFP) for the past two decades. Only

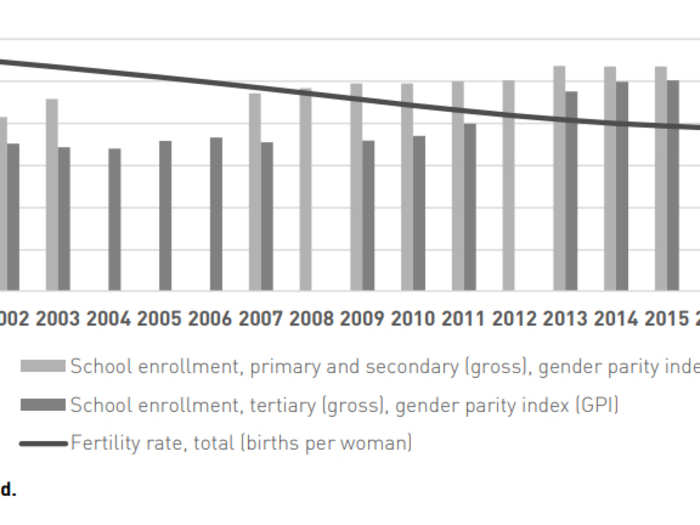

one-fifth of the female population was part of the workforce in 2019, which is one of the lowest globally. But at the same time, India has also witnessed improvements in gender parity in education, higher literacy rates and a downfall in fertility rates.

Thus, the following is puzzling: if the gender parity in education is as high as it has ever been, women are more literate, the fertility rates have fallen to the lowest in India’s history, then why are women still withdrawing from the workforce? There are, undoubtedly, other factors at play that are constraining women’s economic participation.

A ‘

Big Push’ policy strategy is needed to bring women into the workforce in large numbers. This will encourage employers to build a more gender-integrated workplace.

It must be noted that even though social norms only partially explain India’s low FLFP, challenging and mitigating them will be highly beneficial for women in the labour market. The transformation of norms will be an intergenerational process, requiring continuous strategic actions.

Paternity leaves must be at par with maternity leaves, and subsidised day-care services must be made available.

The World Bank

Despite much progress in education and awareness, traditional thought that puts the onus of child rearing on the woman dominates social spheres including workspaces. Absence of childcare facilities and proper creche facilities make it challenging for women to join the labour force when social norms mandate that it's their primary responsibility to look after children.

Meanwhile, the gender pay gap stood at 19% on average and has increased from 2017 when it was 15%. Instead of accepting low paying jobs despite being educated, women choose to remain out of the labour force altogether.

Shift gender norms that define what women’s work should be, through behaviour change communication and media campaigns in their families and communities.

Pixabay

A study found that about 50% of adults believed that a married woman should not be working outside the home if the husband earns a decent living. It is also interesting to note that such norms are “more binding” among wealthier and upper-caste households, explaining the low FLFP in urban India. Thus, it is not surprising that females spent 16.9% of their time on unpaid domestic services and only 4.2% on paid employment compared to men who spent 18.3% of their time on the latter.

Ensure women’s control over their own money and provide capital in-kind instead of cash transfers.

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation 2019

In India, payment of MGNREGA wages into female workers' bank accounts increased women’s participation in the programme.

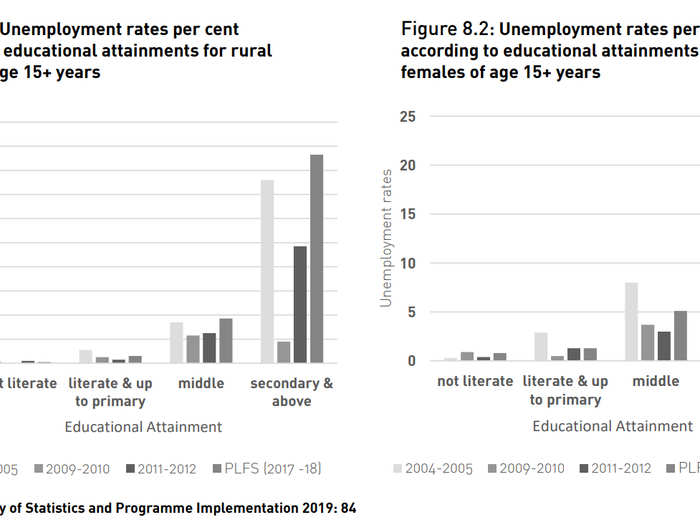

Despite improvements in educational attainment, the unemployment rates among rural and urban women for each level of education shot up post 2011-12. With household responsibilities inevitably falling on women, their employment is seen as a necessity only at times of financial stress in the household income.

As women’s household roles persist, their autonomy is restricted by way of limited access to bank accounts and phones. Only 53% of women have a bank account that they can use themselves, 40% of women hold knowledge of microcredit programmes, and

46% have a mobile phone. Most women depend on word-of-mouth in their families and communities for information on employment and

entrepreneurship opportunities. These norms also limit

women’s network size.

Ensure social security for female workers in the informal sector and women’s safety at work and while commuting.

BCCL

Women also suffer restrictions on mobility, driven by safety concerns. Only 41% of women are allowed to go to the market, health facility, and places outside the village or community, while 6% are not allowed to do any of the three. When curbing women’s freedom is a norm, their participation in the labour market becomes challenging.

Social security must be tied directly to workers, migrant women must be provided with safe and secure infrastructure, and workplaces must strictly adhere to the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act 2013.

Physical security of women

BCCL

Migrant women face safety concerns and the problem of inadequate accommodation, which disincentives them to migrate to cities for work. Unfortunately, due to rampant patriarchy, sexual harassment is also normalised.

The National Commission for Women (NCW) has seen an increase in sexual harassment complaints from workplaces.It’s not just a problem in low-paying jobs or the unorganised sector. A study by FICCI and EY found that 36% of Indian companies and 25% of MNCs were not compliant with the Sexual Harassment Act 2013.

Unfavourable labour laws

BCCL

Women are prohibited from working night shifts in specific factory processes, underground mines, and several other industrial operations, which indirectly set standards for what is considered women’s work. Since paternity leaves are not at par with maternity leaves, it might also reinforce social norms against working women.

Since small and medium businesses and start-ups might be unable to afford to pay maternity benefits or have an employee on leave for long, they might prefer not to hire females at all.

Organisations must diversify women’s jobs away from those that are extensions of domestic care work.

BCCL

Social norms must normalise women in these new roles, or it will inevitably lead to unemployment.

Most women are employed in agriculture and manufacturing, both of which have witnessed the slowest job growths, indicating that demand for female labour supply has taken a hit. Professions dominated by women such as teaching, nursing, domestic help, and so forth are extensions of the care work women undertake at home. Thus, the social norms that define household work as women’s primary responsibility also impact the kind of jobs they are offered.

Working women should be celebrated

BCCL

Educated women tend to marry more educated men who earn higher incomes. When the household income increases and the reliance on the women’s earnings falls, it incentivises women to drop out of the labour force and focus on their “status production”. Families and caste groups gain status by a woman’s seclusion from the labour market, except in cases of white-collar governmental jobs, which are considered highly respectful and thus, receive family support.

Men control women's lives under patriarchal institutions to a large extent, and women’s own internalised patriarchy influences the labour market decisions they make.

According to the National Family and Health Survey (2015-16), 16% of surveyed women do not participate in decisions regarding their own healthcare, household purchases, and visiting relatives. For 17% of women, their employment decisions are made by their husbands.

Akshita Sharma, the author, is a Research Associate at Social and Political Research Foundation (SPRF). Headquartered in New Delhi, SPRF is a policy think tank.