Here's What Life Is Like On The Notorious Wind River Indian Reservation

The Wind River reservation in central Wyoming is surrounded by a landscape most people have never seen.

This craggy honeycombed grotto was unearthly enough to prompt a Hollywood director to film a popular '90s movie here.

And as the miles peel away and the reservation gets closer, it's hard to miss the railroad that's been steaming through here for over 100 years.

Antelope are everywhere ... until hunting season, at least, when locals say they all up and disappear.

Up along the reservation now, signs like this abound to memorialize a vicious event carried out by the Colorado territorial militia.

In 1864, a group of about 800 Northern Arapaho Dog Soldiers left their camp under a flag of truce to go make peace with U.S. troops. In their absence, U.S. Army Colonel John Chivington swept in and murdered the women and children left behind.

Covington and his men hunted down as many as 163 women, kids, and elderly tribes-people. This monument marks the location of the massacre in Colorado, but the reminders at Wind River are far more prominent.

Tribal art based on the massacre from the time are graphic and hang everywhere.

Indeed, the past out here sometimes speaks more loudly than the present.

Out 'here' is the 3,500 square miles where Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes share unforgiving land that neither tribe called home until the U.S. forced them to in 1868. Before being forced to share the same reservation, the two tribes were enemies.

The locals call Wind River the 'Rez' and it's not far from the town of Shoshoni.

Shoshoni is peppered with abandoned buildings stuffed full of the odd mix of tools needed for life here.

Wind River is so large that it surrounds a handful of towns on all sides. Strangely, this makes it feel even more remote than it is.

With all this space ...

... and hardly a neighbor for miles ...

... you might think Wind River was a peaceful place where native culture quietly carries on into the modern day.

But you'd be wrong.

Wind River is in fact a particularly deadly place to call home.

The locals refer to different streets by famously violent U.S. locations like "Compton" in southern Los Angeles.

The New York Times came out here last year after the brutal murder of a 13-year-old girl by her brother and a friend at this trailer.

The pictures are blurry, because when I raised the camera to take them, the school teacher who was showing me the reservation screamed that I was going to get us killed. She did not view this as an exaggeration. She seemed genuinely terrified.

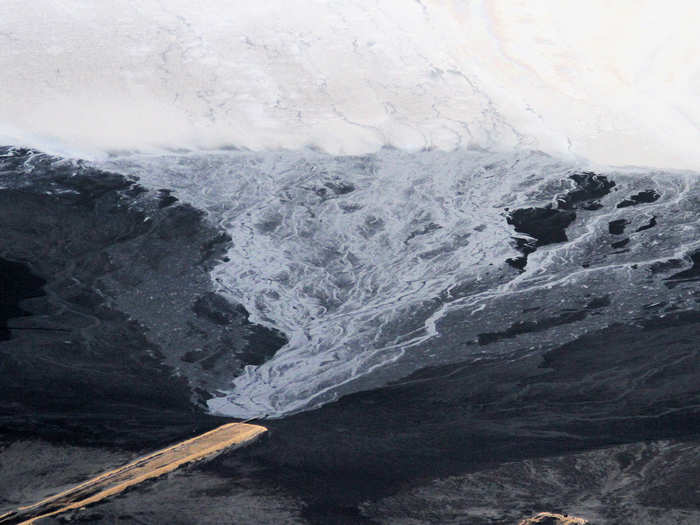

Wind River may also be one of the most actively polluted places in the US.

Last year, NPR revealed that oil companies operating on the reservation are using a legal loophole to justify allowing oil wastewater to flow freely into open pits on Wind River. (This is a picture from an oil mining operation in Canada, but you get the idea).

The toxins in the waste-water leech into water used by Wind River ranchers. It winds up in the steers (and, thereby, in the beef).

That beef is likely part of the wide selection of fresh meat here at a store in the center of the Rez. Interestingly, the grocery store sells no alcohol.

Neither do any of the reservation's four casinos.

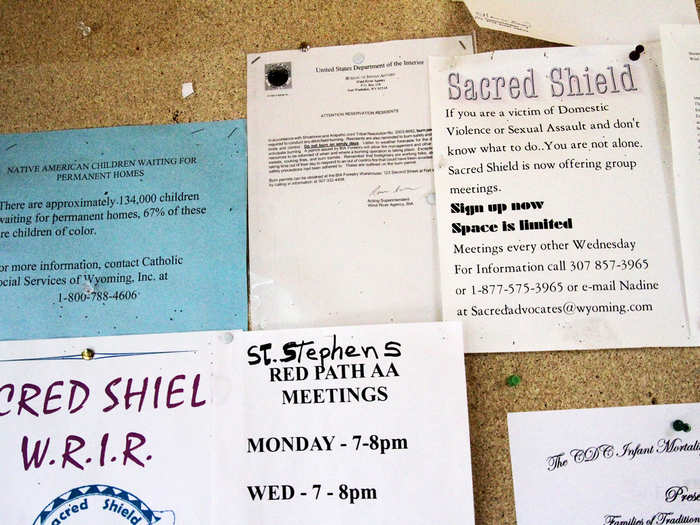

The dry Rez is an effort to keep alcoholism, and the domestic issues that follow it, at bay.

The closest place to get a drink is here, at a bar just off the reservation. Behind the steel door are a couple of pool tables in a room wallpapered with centerfolds and pages from porn magazines.

The "no alcohol" tactic hasn't worked particularly well. This Riverton, Wyoming park is another popular drinking spot among Wind River residents and can fill with people from the Rez.

They call themselves "Park Rangers."

The teacher I am with says her students sometimes have to come here looking for their parents.

A Christian revival was underway when I visited the park. Music filled the space and a preacher urged people to come forward and accept Jesus.

The school is not far and I walk over to look around. Its central architectural feature is a representation of a gigantic tom-tom. Life here is heavy on tradition that fights with the present.

Drug abuse is rampant — from school-kids "huffing" Axe body spray, to alcoholism, to crystal meth throughout the state.

For everything intense and sharp here there seems a counterpoint. If next door were a house that feared drive-by shootings — there is another home within sight that fixes traditional lunches and sells them to school staff.

My guide says everything is for sale on the Rez--in some way or another. Because there is so little law enforcement, crime is high, and law breakers can hide almost indefinitely from police. She had no explanation for why there are so many dogs wandering about.

But they're everywhere. In all sizes.

From animals to residents, those who call this place home must adapt to a clash of culture and unexpected tradition.

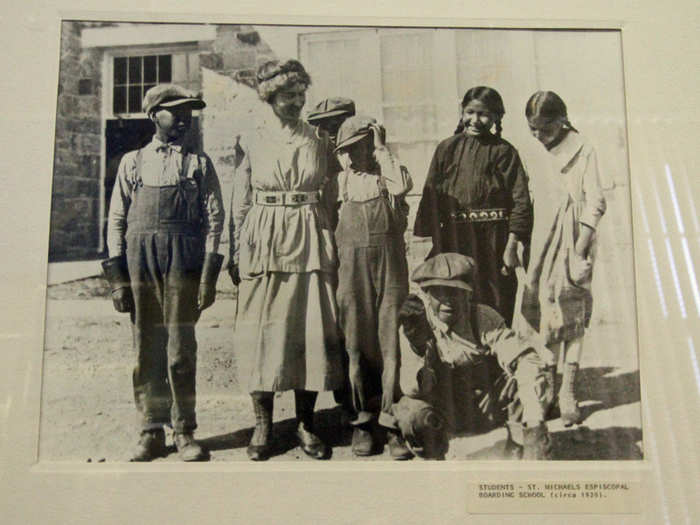

This traditional classroom once taught generations of natives. The likelihood a student on the reservation today will go on to complete college is slim. And anyone showing too much desire to leave is called an 'Apple' by classmates: red on the outside, but white within.

It's a label students try to avoid at all costs.

The most prominent European presence on the reservation is still the Catholic Church.

Like everything else here, Catholicism on the reservation is a blend of native belief and outside tradition.

Not far from the church is the reservation's community center and post office.

Inside are more reminders of Wind River's painful past, like this photo of native children at a boarding school where native dress, language, and belief was forbidden.

Today the cultural center forbids children from speaking English within its walls as it passes down the native dialect.

American influence may be resented, but federally-subsidized programs are close at hand.

As we pass the community health clinic, my guide says growing up here can foster a sense of entitlement.

Food is provided by this distribution center and all residents receive monthly checks from oil revenue.

That modern assistance comes amid constant reminders of the past.

There's a fatalism here that's hard to describe.

An unfocused anger.

And, before I leave, I am told not to come back alone.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement