Why Wall Street traders are obsessed with Jesse Livermore

Jesse Livermore was born in 1877 to a family of farmers and learned to read and write by the time he was 3 1/2.

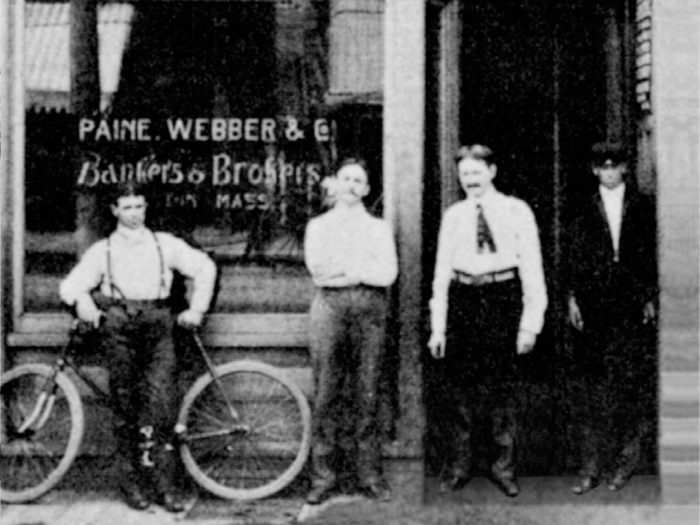

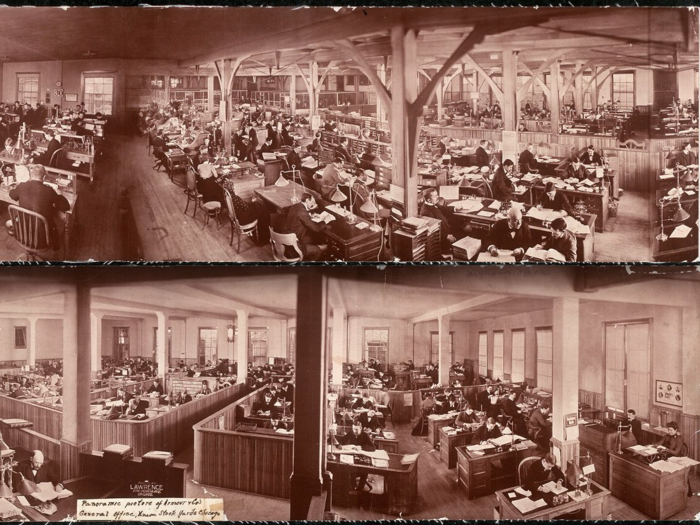

At 14, he charmed his way into a job as a board boy at banking company, Paine Webber.

Instead of going to the address set by his mother, young Jesse Livermore persuaded the driver to stop at Paine Webber, a Boston stockbroker.

He was enthralled.

At the time, Livermore appeared six years older than his age, and "people immediately trusted him and ... Jesse Livermore always repaid that trust," Rubython wrote.

He got a job as a Paine Webber board boy on $5 a week.

He bought his first share at 15 and got a profit of $3.12 from $5 after teaching himself about trends.

Livermore tracked the ticker numbers in his journal and realized there was nothing random about them.

Finally, at 15, Livermore decided to take a dip with a miniscule portion of the profits he had, and earned a profit of $3.12 by putting down $5 at a bucket shop. In a matter of weeks, Livermore's earnings at the bucket shops exceeded his earnings at Paine Webber.

He left the broker at 16 and started trading in Boston's bucket shops.

But Livermore always won ... and the bucket shops took notice. They kicked him out repeatedly. He put on a beard.

He would simply don disguises — a beard — to get under the radar.

Eventually he was permanently banned, though he carried home a small fortune — $10,000.

Livermore decided it was time to challenge his abilities in 1899. He went to New York and married a woman he had known for a few weeks.

In the same year he would meet his wife, Nettie Jordan. They would be married within a few weeks of meeting, and they would be separated within a few months of marriage.

He had lost everything by playing by the ticker's number, which lagged 30 to 40 minutes behind the real-time market numbers.

He had asked Nettie to pawn off some of the jewels he had gifted her to trade again, and she was incensed.

Defeated but confident, Livermore went back to basics. He started making money at St. Louis bucket shops.

That was before the owners recognized him as "Jesse Livermore." Since the shops no longer accepted him, he sent in someone to trade for him and dragged out $5,000 from the shops.

In 1901, Livermore made money almost effortlessly, before losing it all trading cotton.

Livermore had returned to Wall Street to a roaring bull market in 1901. Then 24, he would make $50,000 — and lose it trading cotton.

He would also continue to trade conservatively, too afraid of going too far.

"When I should have made $20,000, I made $2,000," he said. In the meantime, he would enjoy his life as an attractive, wealthy bachelor in the city.

At 28, Livermore had $100,000 to his name by 1906 — but he was losing confidence. So he went on vacation to Palm Beach, but not before he decided to short Union Pacific stock.

His conservatism combined with his inconsistent history of wins of the stock market made him question his long-term ability to trade stock. So he decided to take a break at Palm Beach — it turned out to be a turning point in his life.

Livermore had a "psychic surge" he'd never felt before and decided to short Union Pacific stock.

His friends all thought he was crazy, or had insider information. Union Pacific stock was going up the whole time.

He returned to the city, and then heard about San Francisco's earthquake — which caused Union Pacific's stock to go down. Suddenly Livermore had made $250,000 — though he rued his caution since the market continued to fall after he covered.

His friends all thought he was crazy or had insider information.

Livermore listened to a mentor and decided not to turn his position around — and later discovered shorting the stock cost him $40,000.

Not long after, Livermore tried to buy Union Pacific stock, seeing the proper conditions to buy in the numbers.

But an old friend, Ed Hutton, who had no investments in the company, went out of his way to call Livermore and warn him against the move. Hutton turned out to be completely wrong.

Livermore blamed himself for taking the tip.

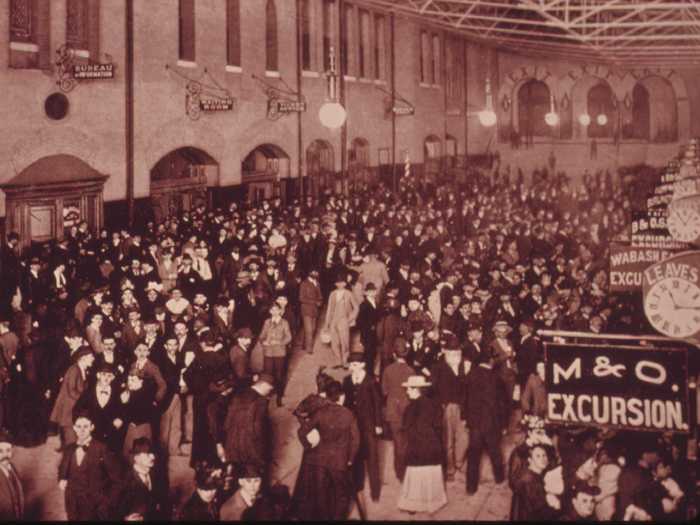

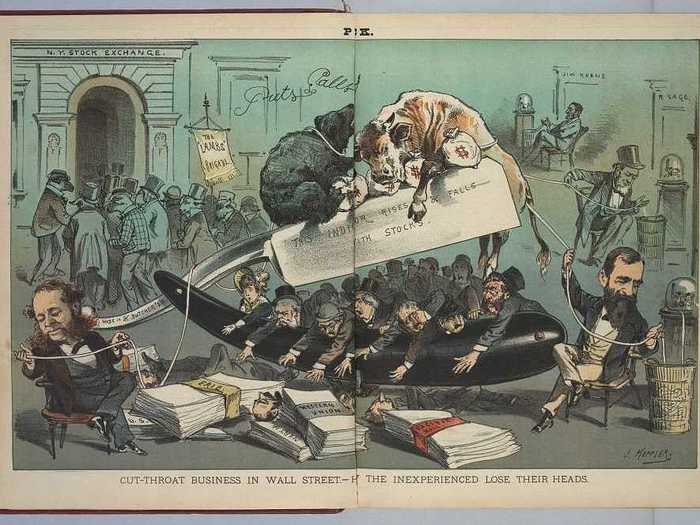

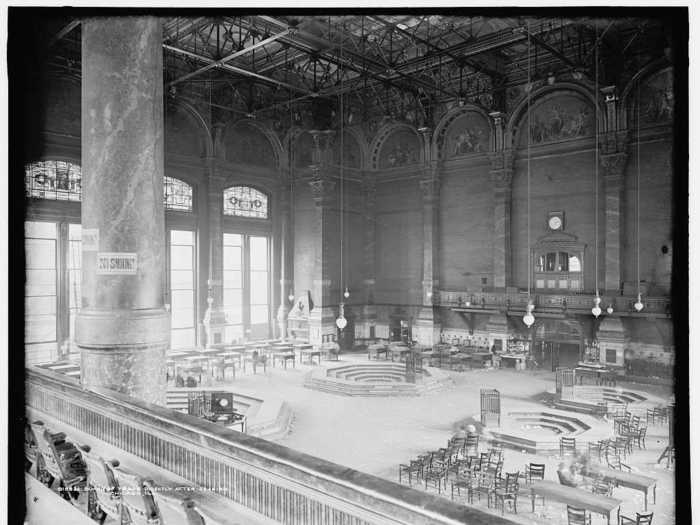

Livermore earned the reputation of a hero in the crash of 1907. As the stock market started plunging, he went short on a hunch.

Livermore earned his largest sum yet: $1 million in a single day.

But seeing the market in crisis, Livermore decided to do the right and wise thing. He started buying all that he could carry (in part at the behest of JP Morgan). His buying led many other Wall Streeters to do the same — and the market started to recover.

Livermore also gained hero status. By following his lead, many of his peers had become rich.

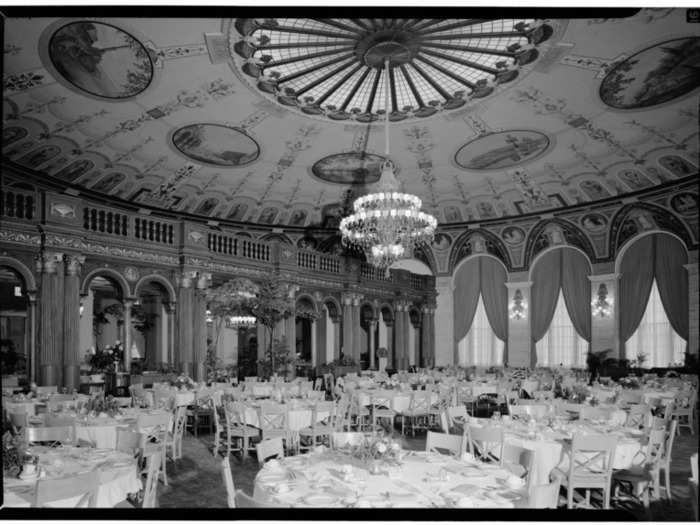

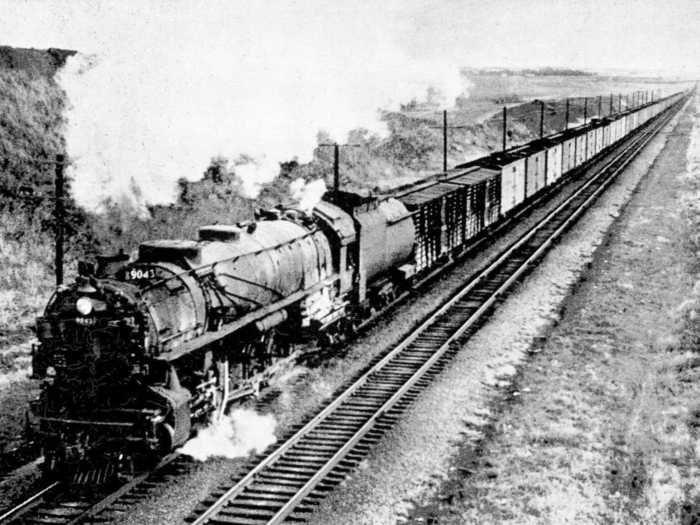

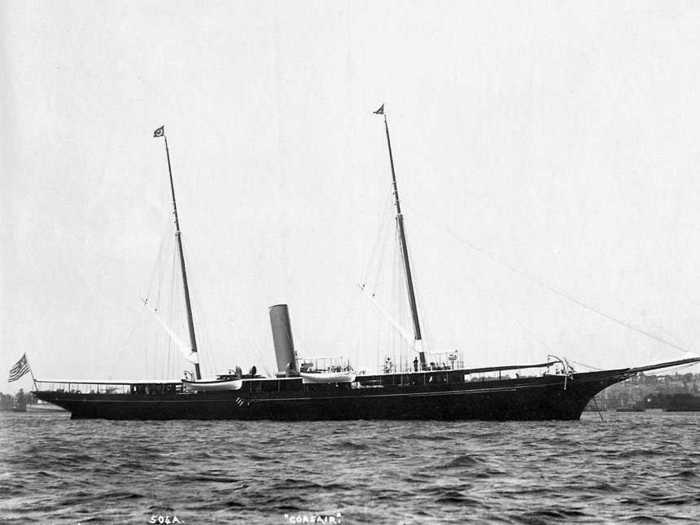

He bought a $200,000 yacht, a rail car, and an apartment on the Upper West Side. He joined the most exclusive clubs and had a stream of mistresses.

In a year, he went from zero to $3 million and entered a new class of wealth.

But the more he bought, the higher the cost of maintenance. Soon, Livermore returned to the stock market.

In 1908 Livermore was betrayed by a "friend" — and paid millions for it.

Livermore had $5 million to his name and earned his moniker "boy plunger" — before losing it all trading cotton in the Chicago commodities market.

He had listened to Teddy Price, a famed cotton trader — and he couldn't explain why he had listened since he knew the position was wrong. While Price told Livermore to continue buying, Price himself sold, along with the rest of the growers.

Livermore was sunk.

He was bankrupt for a year before he made it all back. Then, at 40, he proposed to 22-year-old Dorothy of the Ziegfeld Follies.

Bankruptcy was inevitable in 1915. The stock he had bought in 1907 to ameliorate the market crash came back to cushion his fall during to succeeding years as the market went through a long bear market.

A year later, he made $5 million back riding the bull market.

Then, after a long and highly publicized divorce from Nettie Jordan (including a stunt where he hired a private investigator to steal back his car), he was finally married to Dorothy, a Ziegfeld Follies dancer.

Dorothy and Livermore would have their first son, Jesse Livermore II, in 1919. By 1922, the couple's second son, Paul, was on his way.

Livermore decided to buy an expensive property at Great Neck and left Dorothy with an empty check to furnish the house.

They were moneyed, high-society, and wanted nothing. It was a period of overwhelming happiness for the family.

Livermore's name also grew in the media, and people bought and sold based on his recommendations in the papers.

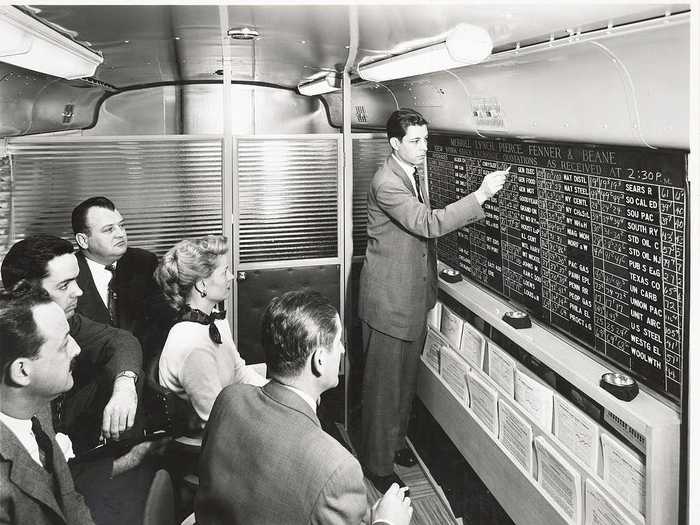

He established a formal trading operation — earning $15 million . Two years later, Livermore would move to a larger office with 60 staff members.

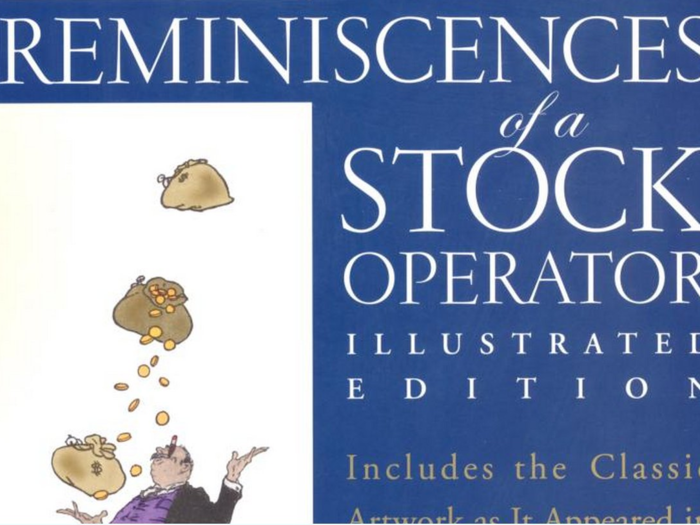

Edwin Lefevre contacted Livermore in order to write 'Reminiscence of a Stock Operator.' It was published in 1923.

At its publication, no one realized it was a thinly veiled disguise for Livermore's own life, with a character named Laurie Livingston repeating the words Livermore had sat down and said to Lefevre.

It would do surprisingly well and spawn several reprints.

In the same year, Livermore second son was born.

Meanwhile, his notoriety continued to grow on Wall Street. He made $10 million trading wheat and corn in 1925.

He would make $10 million trading wheat and corn in 1925 on the Chicago Board of Trade — battling the famed bullish commodities trader Arthur Cutten for the ability to manipulate the market.

In 1927, two burglars broke into the Livermore's home and held him and his wife at gunpoint.

Dorothy was surprisingly calm throughout the ordeal, talking the burglars into leaving some of their most valuable jewels behind. When they left, she persuaded the burglars to leave carefully and not to wake the children.

Despite the family's happiness however, things were beginning to change. Dorothy's drinking habits were getting out of hand.

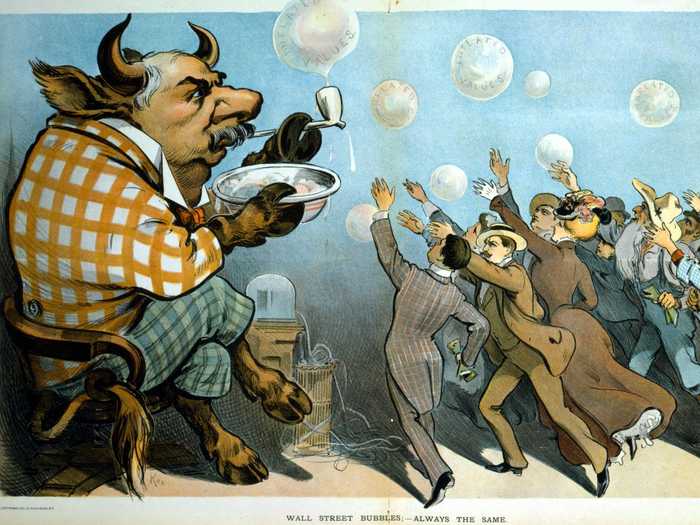

Then Black Tuesday hit and the market crashed. Livermore made $100 million going short.

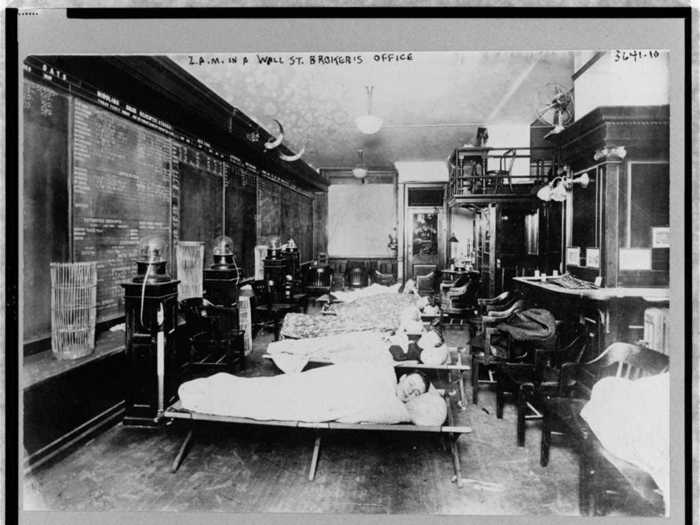

By chance, Livermore felt something was moving in the market. He decided to live out of his office making trades in the days leading up to October 29.

As the news began spreading about traders who had lost everything on Black Tuesday, Dorothy Livermore and her mother at home in Evermore began panicking. When Jesse Livermore returned, they were crying about how they were ruined — not realizing he had made $100 million going short.

By 1932, Dorothy's drinking habits, combined with Livermore's affairs and their lavish spending habits, strained the relationship.

Throughout their relationship, Livermore had kept mistresses from everywhere — including the Ziegfeld Follies, where Dorothy still had friends. She was humiliated.

At the same time, Dorothy's drinking habits had turned her from the life of the party into an undignified drunk.

Dorothy asked for quick divorce and received the modest settlement of $10 million. She took custody of the boys as well as the house. On the same day, she married a younger man — a former prohibition officer.

At 56, Livermore, no longer young nor truly wealthy, decided to spend the last of his money on vacation — where he met his third wife.

He met the American singer Harriet Metz in Vienna. Four times widowed by suicides, she had her own money from those deaths.

Livermore planned on using the vacation to recuperate and make a comeback from inevitable bankruptcy upon his return to New York. But he was also emotionally worn out.

Dorothy attempted to keep up the lavish lifestyle her ex-husband had given her, but didn't have the funds. She sold the Great Neck house. The sale of a home that had been part of the family for a decade hurt Livermore.

The house had come with butlers, maids, cooks, gardeners and more — and $10 million was not enough to keep it running. Dorothy had divorced her new husband. Livermore sank deeper into depression. The house has represented a decade of family and joy, and it was sold and torn down.

Jewels and an inscribed wedding ring that Livermore had given Dorothy were sold for a few dollars — Livermore felt humiliated.

The house and renovations had cost Livermore $3.5 million. Dorothy sold it all for $222,000.

A year later, Livermore was forced to declare a third bankruptcy.

It was Livermore's third time, but as before, he was confident he could make a return to the market.

He had friends and had done it before.

But that third and final era of debt in his 60s would be fatal. Though Livermore had famously returned to the stock market twice before, the creation of the SEC and loss of the motivation that had prompted his previous phoenix risings would lead to a dead end.

In 1935, Dorothy Livermore shot their son Jesse Livermore Jr. while in the middle of a drunken spat.

Jesse had always been a problem child, drinking like his mother and sleeping with her friends.

On Thanksgiving, Dorothy and her new husband had lunch with her two sons. After the meal Dorothy sat down and began drinking liberally.

Jesse Livermore Jr., upset over her deteriorating drinking habits, finished off the bottle. His mother said, "I'd rather see you dead than drinking that way," to which he replied, "you don't have the nerve to shoot me" and handed her a gun.

She was inebriated, and after a prolonged argument, the gun went off.

She was taken in for questioning, Jesse Jr. narrowly survived, and she was cleared of charges.

The situation added stress to Livermore's life.

Jesse Livermore began to realize after a series of family tragedies and the emergence of the SEC that he might not trade the same ever again.

His wife's fortune also supported him comfortably enough that he felt no urgency to trade.

In 1940, Livermore's book, "How to Trade in Stocks," was published, though it was never as popular as Lefevre's work.

“No man can always have adequate reasons for buying or selling stocks daily — or sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play,” he said to Lefevre.

And in the same year, Livermore shot himself in the coatroom of the Sherry Netherland Hotel in New York.

According to Rubython, his wife's $7 million fortune had lulled him into a sense of comfort and killed the desperation to win he had in his youth.

He felt as if he was losing himself.

He left nearly no money to his children. Jesse Livermore Jr. later committed suicide.

What little he had allocated to their trust funds had devalued over the years. Jesse Livermore Jr. would also fall into the habits of his alcoholic mother and kill himself in 1975 after shooting his beloved dog while drunk and attempting to shoot a police officer.

As did Jesse Livermore Jr.'s son.

"There is nothing new in Wall Street. There can't be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again," Lefevre wrote.

Though his money didn't last, his wisdom stayed with generations of traders, and his mistakes became the encouragement and lessons for traders today.

"If a man didn't make mistakes he'd own the world in a month. But if he didn't profit by his mistakes he wouldn't own a blessed thing," Leferve wrote.

Want to know what else Wall Street is reading?

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement