These charts explain the 'Politics of Rage' - the cause of Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump

Barclays' first chart provides a breakdown of each factor it believes has contributed to the growing rage among regular people across the West. Economic and political globalisation sit at the very heart of the problem, although their impact is actually more limited than might be expected.

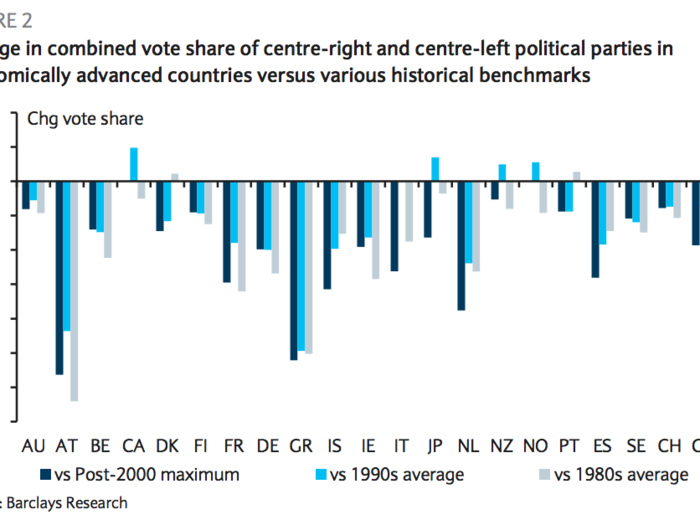

The rise of the "Politics of Rage" is most clearly illustrated by the collapse of support for centrist parties across the world's developed economies in recent years.

Barclays provides four key bullets alongside its chart, saying:

- "We measure the Politics of Rage by the change in the combined vote share of centre right and centre-left political parties – the centre vote share – across countries."

- "The centre vote share has collapsed across advanced economies by an average of 12pp since the 1990s and as much as 62pp in Austria. Only Japan and the commodity exporters have avoided a significant drop in the centre vote share."

- "The collapse in the political centre began in the early 2000s in most countries, before the Global Financial Crisis, but in recent years has accelerated."

- "There is no historical precedent we can find for the current widespread collapse, not even during the Great Depression years."

Globalisation may be important, but it is not the most important thing, Barth argues.

"The impact of globalisation, particularly immigration and trade, are important sources of voter rage; but surprisingly they are not the most important, and we find evidence that angry voters’ concerns in this area are not clearly economically irrational."

Normal citizens increasingly perceive that governments and supranational organisation are not representing their best interests.

"The biggest source of voter rage appears to be a sense of economic and political disenfranchisement due to imperfect representation in national governments and delegation of sovereignty to supranational and intergovernmental organizations."

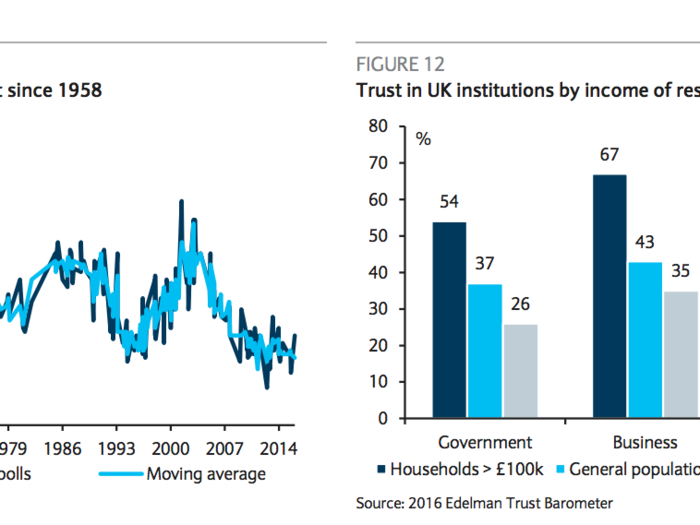

One of the big drivers of the rage felt across the world has been falling trust in political institutions and governments in particular.

"Citizens of all levels of education and income have lost faith in their governments, businesses, press, and other institutions, but the deterioration appears greater for lower-education and lower-income groups. Figure 11 [above] shows the decline in Americans’ trust in government to historic lows over the last half century.

"According to Pew Research Center, 74% of Americans believe that “most elected officials put [their] own interests ahead of [the] country’s,” and that elected officials are less intelligent, less honest, more selfish, and more lazy than either business leaders or typical Americans.29 But it isn’t just Americans who feel this way. UK voters, too, are less trustful of the government than business, though the media engenders even less trust (Figure 12), a trend that also is apparent in America."

A divide between the ancient Greek societal groups, the "demos" — normal folks, and the "aristokratia" — the so-called "elites," has intensified in recent years.

"A final hypothesised cause of the Politics of Rage is a growing cultural and economic division within society that we will call – in keeping with our classical Greek analogies and to avoid possible pejoratives – the “aristokratia/demos divide”," Barth argues.

"The precise divide is hard to define as it is correlated with, but not necessarily delineated by, education and income. But there is a clear sense in political discourse of a division between the “broader citizenry” and what are perceived to be “elites” in government, business, media, academia, and institutions."

Barclays then cites key Brexiteer and failed Conservative Party leadership challenger Michael Gove's now famous assertion that Britain is sick of "experts," as a key illustrator of this phenomenon.

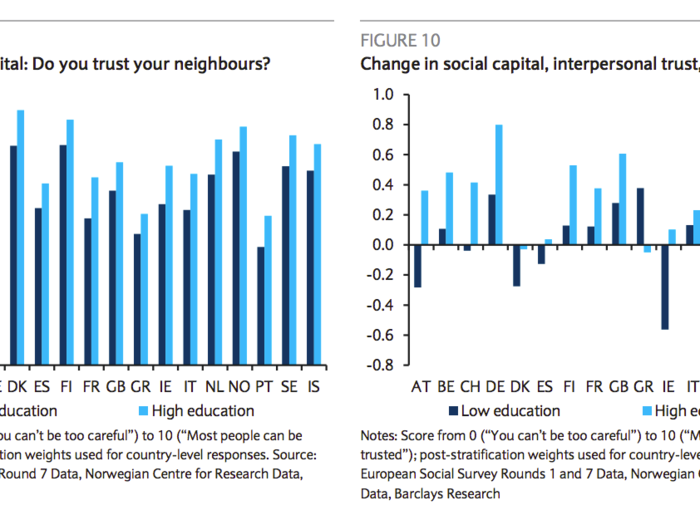

Social capital has also played a big role.

Social capital is essentially the glue that helps hold societies together. Factors such as how much people trust their neighbours play a big role in social capital scores. As Barth writes:

"It usually is measured by trust in one’s fellow citizens and perceptions of personal safety. Figure 9 shows the divergence in levels of interpersonal trust between low- and high-education respondents. In the past decade, interpersonal trust rose among high-education respondents across Europe, on average, while low education respondents, on average, reported no gain in trust and in nearly half of the countries surveyed witnessed declines (Figure 10)."

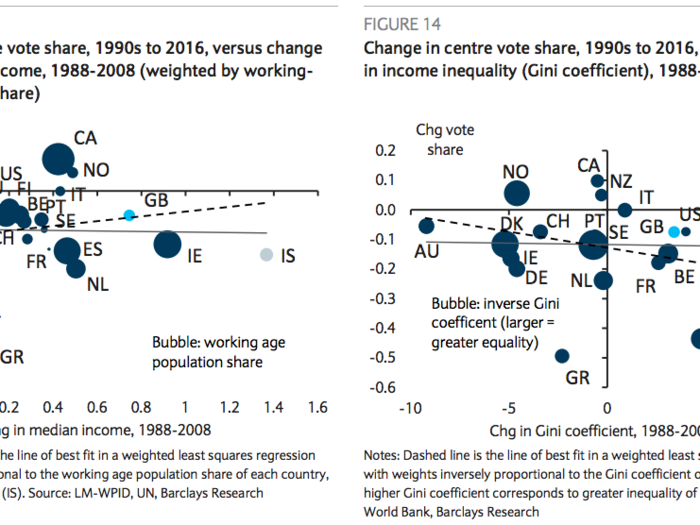

While income inequality is often cited by policymakers as a driver of increasing anger with politics, but this is not the case, according to Barclays. It is actually the combination of growing frustration with experts, an erosion of social capital, and frustrations with globalisation at large that has driven society's growing rage.

"Several sources have suggested that rising inequality is behind voter rage. Policymakers in particular appear to have focused on this phenomenon as a cause. In its latest communiqué, the G20 vowed to address sources of inequality, and the topic has become a cause célèbre for IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde."

"A related view, endorsed by Dr Milanovic and, as noted previously, generally accepted by the G20, is that increasing income inequality is a strong source of voter anger. However, as shown in Figure 14, this hypothesis is only weakly supported by the available data. Changes in Gini coefficients – an increasing measure of income inequality – over the same 1988- 2008 period are unrelated to the change in support for the political centre, as illustrated by the solid line of best fit in Figure 14."

Popular Right Now

Advertisement