Meet the 30 biotech leaders under 40 who are searching for breakthrough treatments and shaping the future of medicine

Krishna Yeshwant, 39, is searching for unconventional healthcare startups to back.

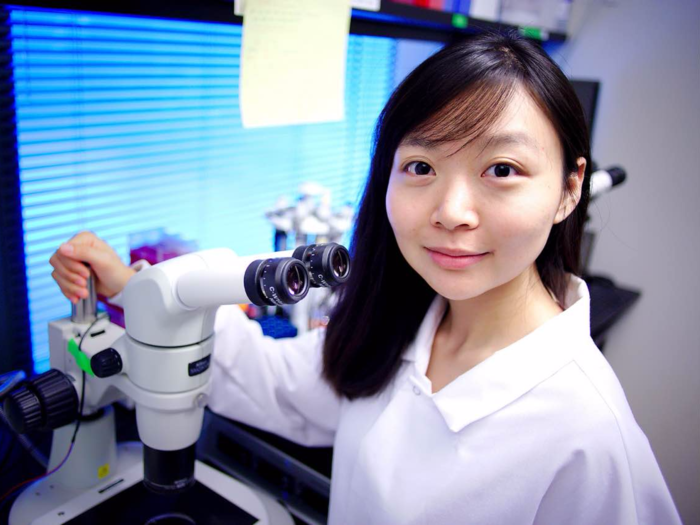

Luhan Yang, 31, is making it safe to transplant pig organs into humans to help the hundreds of thousands of people waiting for transplants.

Luhan Yang, chief scientific officer at eGenesis, was born and raised in China, where she studied psychology and life sciences before moving to the US to get her Ph.D. at Harvard. It was there where she met George Church and started working with the human genome, and ways to modify it, especially using the CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Her work in the lab led to her and Church in 2014 founding eGenesis, a company that's using the CRISPR to make pig organs viable for transplants into people, an advancement that could impact the hundreds of thousands of people waiting for transplants around the world.

There are two huge hurdles to getting animal-organ transplants to successfully work in humans — a process known as xenotransplantation. The first is the virus, which in August the eGenesis team managed to get past when it had produced 37 piglets that had inactivated Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus, or PERV. The work set a record for the most complex edits made with CRISPR. The virus, which is part of the pigs' DNA, has been an issue for human-pig transplants in the past because of concerns that it could infect humans.

The second that Yang and eGenesis are still working on, is the immunology. Since the pig organ would be foreign to the body, the person's immune system might try to kick it out, rejecting the organ. Those proved too challenging for a slew of researchers going after this subject in the 1990s, but Yang is hopeful that her approach of building up the company's platform will help researchers get to the heart of the issue.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Bringing in a more global perspective to medicine. For example, Yang's background led her to work with xenotransplantation, she said, in part because of the historically limited access to donor organs Asian countries have had for transplants.

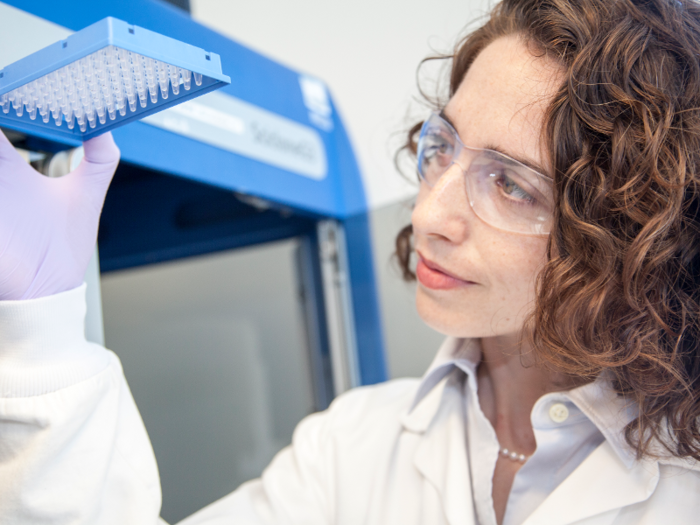

Erica Weinstein, 30, helps turn crazy ideas into the experimental drugs that startups research and develop.

Erica Weinstein, an associate at the venture firm Flagship Pioneering, wanted to ask "why not" during her doctorate research in immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mout Sinai. She was interested in taking seemingly "crazy" ideas and turning them into therapies that could be developed and one day help treat patients. So Weinstein joined Flagship in 2015 to put those ideas to the test.

"That questioning is what Flagship does," Weinstein said. There, she's helped develop the pipelines of new startups, helping them go from a concept to a team of 20 to 30 people. So far, she's cofounded Cygnal Therapeutics, which is working on treatments for cancer, immunologic diseases and regeneration, and two companies that are still in stealth mode.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: The passion to bring life-changing therapies to reality and by being willing to think, "This feels weird, but I'm probably going down the right path," Weinstein said.

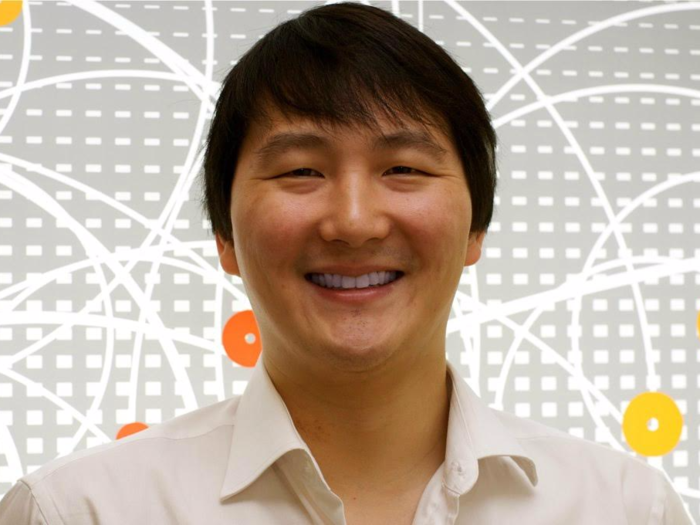

Masoud Tavazoie, 37, and David Darst, 36, are building a cancer drug company in the heart of NYC.

Masoud Tavazoie, Rgenix's CEO and cofounder, is a physician-scientist who studied at Columbia University. Prior to joining Rgenix in 2013, David Darst, chief operating officer, cofounded the pharmaceutical company Apellis Pharmaceuticals, got his MBA from Harvard University, and worked for the venture-capital firm OrbiMed.

The inspiration for Rgenix, which started in 2010, was based on the fact that some cancer patients don't have good chances of survival based on the drugs approved. The hope with Rgenix is to find new targets — and drugs that act on them — that might do a better job of confronting cancers that might not otherwise respond. The company's lead cancer immunotherapy drug is in a phase-one trial, and Tavazoie said he expects to do future studies that combine the experimental drug with approved cancer immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Tavazoie said it'll be that people will be more flexible and open to new technology when it comes to drug development. Darst said the contribution will be going beyond some of the recent cancer developments, especially in immunotherapy, to looking for fewer "one size fits all" approaches.

Stephanie Tagliatela, 29, and Kartik Ramamoorthi, 31, want to bring cutting-edge technologies like gene therapy and gene regulation to patients faster.

Kartik Ramamoorthi, cofounder and CEO of Encoded Genomics, and Stephanie Tagliatela, the company's cofounder and chief scientific officer, met while they were Ph.D. students in the brain and cognitive-sciences department at MIT. After Ramamoorthi finished his program, he worked at Voyager Therapeutics, a gene-therapy company developing treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. It was there that he got the idea to start his own company that focused not just on gene therapy but gene regulation as well.

Gene regulation is the mechanism through which some cells express certain genes and others don't. So far, there's only one approved gene therapy in the US, according to the FDA. The hope is that by using gene therapy to manipulate the way certain cells express genes, you might be able to treat genetic diseases we have a hard time treating now. The ability to take the concept from idea to patients quickly convinced Tagliatela to leave her Ph.D. work early to join the company on the West Coast.

So far, Encoded has raised $50 million from investors including genetic-sequencing giant Illumina, Arch Venture, and Venrock, and plans to give more details about the diseases they're going after in 2018.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Ramamoorthi told Business Insider that the "under 40" generation will take advantage of all the advancements in genomics by turning them into therapies that go beyond the way we conventionally think of a pill or a biologic. Tagliatela added that drug development could experience big changes thanks to these genomic advancements. "The onset of big data is going to be a really exciting area for drug development that I think our generation will be really key to advance," she said.

Armon Sharei, 30, is 'squeezing' cells to reengineer them so they can help fight off cancer.

Armon Sharei, CEO of SQZ (pronounced "squeeze") Biotech, grew up in Iran and Dubai before attending undergrad at Stanford and later MIT for a Ph.D. in chemical engineering. While working on his doctorate, he developed a "squeezing" platform.

It works by taking out cells from the body, squeezing them so that the cell membrane breaks apart, at which point a protein (in the case of cancer, a protein the tumor cells are expressing) you want to go after gets inserted. Those cells close up, but the protein fragments come to the cell surface and now they get put back into the body where they meet up with the T cells that pick up on that signal and then can go after cells carrying that protein in the body.

The process could have big implications for treating cancer and immunologic diseases. Sharei said the plan is to apply the technology to treating solid tumors, an area current cell therapies haven’t cracked yet. In 2015, SQZ partnered with Roche to develop some of these therapies, in a deal that could be worth as much as $500 million.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Thinking of new ways to approach therapeutics, such as using cells as a therapy, and thinking outside the box to approach problems, Sharei said.

Carl Schoellhammer, 30, came up with a new way to take your medicine that could replace injections.

Carl Schoellhammer is CEO of Suono Bio. During his doctorate at MIT, he worked with ultrasound technology — best known for its use in imaging technology — to see if drugs could be delivered that way.

Here's how that would work: A device that can emit low-frequency ultrasound is paired up with a drug that's part of a liquid solution. The ultrasound creates bubbles in a fluid, which then implode and create little jets that put the drug into a particular tissue in the body.

The method could one day help companies deliver "delicate" therapies made of DNA or RNA, Schoellhammer said. Suono's hoping to get the technology into human trials within the next year.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: That will be to accelerate drug development, in part because of technology and less redundant approaches, but also by bringing the generation's "foolhardiness to try new things," Schoellhammer said.

Mary Rodgers, 35, is a "virus hunter" who makes sure that we can detect infections no matter where it is in the world.

Mary Rodgers, a senior scientist at Abbott Laboratories, has a fun way to describe her role: virus hunter. After attending the University of Madison in undergrad for biochemistry, Rodgers attended a Ph.D. program at Harvard, where her work focused on the hepatitis virus. She then went on to do research at the University of Southern California before returning to the Midwest to work at Abbott.

Her job: Makes sure that we can detect infections no matter where they are, based on Abbott's database of viruses. That can be a big deal for diseases like HIV and hepatitis. Diagnostic tests (which Abbott makes) have to catch all different mutations to the virus so that patients don't get a false negative result. Rodgers' job is to stay ahead of that curve.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: The ability to edit genomics with CRISPR, which could have big implications for infectious disease, Rodgers said.

Vivek Ramaswamy, 32, is creating a new model for biopharma companies by focusing on old drugs that have been abandoned before they got approved.

Vivek Ramaswamy, the CEO of Roivant Sciences, originally thought he'd go to school to be a physician, a scientist, or both. After working in a lab at Harvard, he quickly changed his mind. The time it took to develop a drug from start to finish was just much too long.

So he went to be an investor, and from there he saw a lot of companies with narrow focuses and he decided to take a different approach by building subsidiary companies that would bring drugs that other companies had left on the shelf for one reason or another. Since starting Roivant, the company has created six subsidiaries, two of which have gone public. In August, Roivant raised $1.1 billion from investors including SoftBank.

But in September, Roivant's first subsidiary Axovant got bad news: Its late-stage Alzheimer's disease drug had failed a key trial, putting a dent in Ramaswamy's thesis.

"Some of those efforts will succeed. Others will fail," Roivant said in a statement after the trial results. "We owe it to patients to take those risks, and we remain undeterred in pursuing our mission."

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Ramaswamy said the defining impact this generation would have on medicine would be "a greater penchant for the inclusion of technology in drug development." This generation will also have a greater focus on social purpose, he said.

Maria Pereira, 31, built a material that could change the way we reconstruct tissues in the body.

Maria Pereira, chief innovation officer of Gecko Biomedical, went to MIT after studying pharmaceutical sciences in Portugal. As a Ph.D. student in bioengineering, she worked on a project with the Boston Children's Hospital, working on better ways to repair and regenerate hearts, particularly in babies. The problem wasn't easy to solve, but in the end it led Pereira to develop a material the consistency of honey that when a certain light's applied turns into a bendable, dissolvable structure.

"I always liked to create," Pereira said. From there, she was able to turn her project into a company. The platform of polymers she created have the potential to work as a sealant, as a 3D structure that acts like scaffolding to help tissue grow around it, or as a way to deliver drugs that slowly release as the material breaks down. Because the substances are biodegradable, allowing the body to heal on its own, it could transform certain surgical procedures that currently leave lasting implants in your body.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: The younger generation of leaders is used to moving fast and has been exposed to technology starting at a young age. The under-40 generation, she said, will have a chance to "go beyond" and bring different areas of science and technology together.

Ian Peikon, 30, is working to find the link between the gut and the brain to transform how we treat neurologic diseases.

Ian Peikon, a senior scientist at Kallyope, is in charge of the sequencing the cell types in the vagus nerve in the brain, which is connected to the gut. The work builds on what he was working on while earning his Ph.D. from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, which included using DNA to map out the connections in mouse brains.

Instead of treating diseases of the brain by trying to get treatments into the brain, Peikon and Kallyope are trying to figure out how exactly the brain interacts with the gut. Understanding that relationship could lead to pills that could interact with the gut's signals and in turn pass that message along to the brain.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Peikon said it would be by finding ways for scientists to collaborate across disciplines, like, neuroscientists working with gastroenterologists.

Anupam Pathak, 35, is using his background in engineering and tech to make life easier for people living with tremors.

While working on his doctorate in engineering, Anupam Pathak, now the technical lead at Verily, developed technology that helps stabilize unwanted movements. With the help of neurosurgeons at the University of Michigan, he came up with ways to help people living with Parkinson's disease, essential tremor and other conditions with movement impairments take on every day tasks, starting with eating.

That technology became the basis of Liftware, a company Pathak started that's now a part of Verily, Alphabet's life-sciences company. The group now has two products, one to help stabilize eating utensils for people with tremors, and the other for people with other conditions that leave them with limited motion. Pathak told Business Insider that the hope is to use the technology to potentially create other tools folks with motion problems might need throughout the day and "rethink what it means to be disabled."

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Helping out with the aging population, Pathak said.

Sachin Paranjape, 38, is trying to make diabetes medications even more useful using technology and feedback.

Sachin Paranjape, a medical director for diabetes at Sanofi, works to integrate technology into therapeutics to help make people who live with diabetes healthier. He received his Ph.D. in pharmacology before conducting diabetes research at the Yale School of Medicine and later with Sanofi. As part of the medical affairs department, he works on running trials to help get a better sense of how diabetes medications like insulin work in the real world.

To do that, Paranjape is pulling in data from devices like continuous glucose monitors, which consistently monitors a person's blood-sugar levels, letting you know when your blood sugar is too high or too low and whether it is rising or falling.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Adding technology into life sciences.

Julia Oh, 35, is building microbes that could one day treat our diseases.

Julia Oh, assistant professor at the Jackson Laboratory, had two main loves coming out of her Ph.D. work at Stanford: microbes and synthetic biology, which is the reprogramming of cells to have them do what you want them to do.

Now, through her work at Jackson Labs, a nonprofit biomedical research institution, she's able to combine the two concepts to develop treatments that use engineered microbes to treat diseases. For example, say you had a skin condition (Oh's work is focused on the skin microbiome), instead of treating it with a cream, you could just introduce a microbe to the environment that would live on your skin with all the other microbes you already have. If it sensed that your skin was acting up, it could secrete a chemical that would counteract it. The potential for engineered microbes is broad, Oh said, ranging from autoimmune disorders, to cancer, to bacterial infections.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Oh said it would be embedding technology into biology, including having biologists build that technology themselves. It'll also be the willingness to collaborate with people who are experts in areas the researcher might not know much about, such as physics. "We don't even know the questions they can answer," Oh said.

Geoffrey von Maltzahn, 37, wants to rethink the way we treat diseases by focusing on the microbes that live inside us.

Geoffrey von Maltzahn, a founder at Flagship Pioneering and president at Kaleido Biosciences, grew up with an engineer for a father, and a Montessori teacher for a mother, each with a much different view of the world. Now, through his work as an investor and founder, he's working to transform the way we see biology from his mother's worldview, where concepts are curious and almost magical, to his father's, where concepts are clearly defined and understood.

Von Maltzahn joined Flagship Pioneering in 2009 and received his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering and medical physics at MIT. Since joining Flagship, he's helped found a number of companies including Axcella Health, Seres Therapeutics, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals and Indigo Agriculture. Through his latest companies and investments, he's been focusing on a promising area in science: the microbiome, or the bugs that live in and on us.

The microbiome is basically an untapped system that could help us better understand and one day even treat diseases, almost as if it's a newly discovered organ. "We're missing a whole medical specialty," he said. That could mean, for example, using "anti-antibiotics," or microbes that better counter the bad bugs that make us sick.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Making biology a lot more rational and understood, which could lead to new tools, especially when it comes to understanding the microbiome and what it can do for everything from food to medicine.

Tim Lu, 36, is building startups out of his lab that are making a coding language out of cells.

Tim Lu, associate professor of biological engineering, electrical engineering, and computer science at MIT, runs the Synthetic Biology Group at MIT, where he's worked to develop synthetic biology that's programmed to be more precise therapies.

As an undergrad, Lu studied computer science and went on to focus on the systems going on inside living cells during his graduate work. His goal: finding answers to the question, "How do you program new functions into living cells?" the way a programmer might create new functions for a computer. The concept, called synthetic biology, could help build adaptive therapies that'll be able to go to the right place and do the right thing at the right time.

Lu's been a professor at MIT since 2010, and out of his lab he's helped found a number of companies including Synlogic, a company genetically reprogramming bacteria to treat diseases, and Eligo Bioscience, which raised $20 million in September to fund its work in using CRISPR to kill off harmful bacteria in the gut.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Lu said it will be by viewing biology as a data science, and using that mindset to figure out why diseases happen. That could help us understand why diseases arise and treat them more precisely, he said.

Rebecca Leary, 37, is helping Novartis get the most genetic information out of its cancer clinical trials.

Rebecca Leary, a senior investigator at Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, is working on blood tests to help researchers better understand how a tumor's responding to a particular experimental treatment during clinical trials.

These tests, known as liquid biopsies, look for something called "circulating tumor DNA," or the bits of DNA that are released from dying tumor cells into the bloodstream. It's a less invasive way to get a snapshot of a tumor than a traditional tissue biopsy. The liquid biopsies Leary works with get a comprehensive look at mutations in tumor DNA, especially keeping an eye out for mutations we don't know a lot about just yet.

Leary received her Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University, where she was working with cancer genetics, trying to find new cancer targets, before joining Novartis.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Bringing innovative tools to patients, like those using gene editing, and finding new ways of thinking through medical challenges, Leary said.

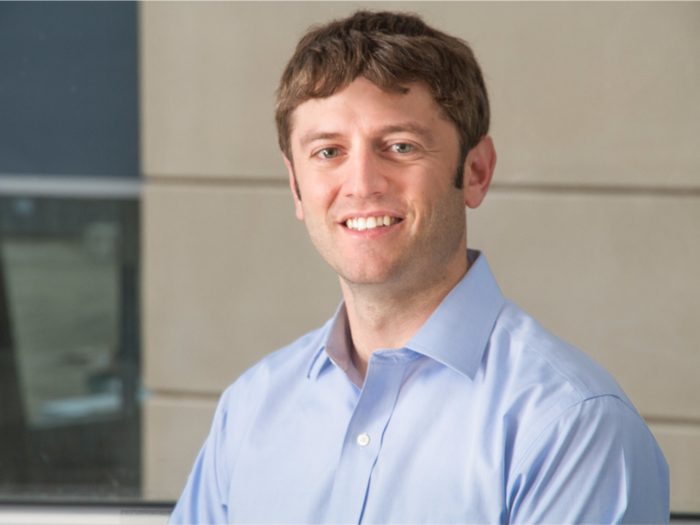

Neil Kumar, 38, is building a new business model to bring more drugs from academia to patients faster.

Neil Kumar, CEO of BridgeBio Pharma, saw a gap between early-stage discoveries that were happening in academics and the companies that wouldn't be interested in that idea until it was farther along in development. Kumar had gotten his Ph.D. from MIT in chemical engineer before working at McKinsey consulting for large pharmaceutical companies and later becoming a principle at Third Rock Ventures and working with companies like Myokardia that are focused on the genetic components of disease.

To close that gap, in 2015, he cofounded BridgeBio, which builds out subsidiary companies around different inherited genetic diseases. In September, the company raised $135 million from a bunch of Wall Street firms to develop treatments for inherited diseases. The subsidiaries are focused on everything from skin conditions to inherited heart disorders.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: It will be keeping things patient focused, but adding in more data, such as patient registries, and new business models to keep things moving forward, Kumar said.

Cigall Kadoch, 32, wants to reverse the effects of cancer by shutting off the genes responsible for spreading cancer around the body.

Cigall Kadoch, a professor of pediatric oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School and cofounder of Foghorn Therapeutics, was in college around the time the first human genome was sequenced, a moment that would shape her career. After the entire genome was sequenced, researchers started looking into the genomes of certain diseases, including cancer.

Through her Ph.D. work at Stanford, she explored a protein complex that seem to be implicated in all of the cases of a type of sarcoma. And by reversing the mutated genes responsible for the protein complex, the cancer could essentially be "reversed," an area of medicine called epigenetics.

Unlike existing drugs, the idea here is to reverse the effects of cancer by shutting off the genes responsible for spreading cancer around the body. The genes that'll be shut off are "master gene controllers," Kadoch said, meaning they're responsible for what's causing to spread around the body. In 2016, Kadoch cofounded Foghorn Therapeutics as a way to turn her work in reversing the effects of mutated genes into treatments.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Translating those gene mutations that we understand are connected to cancer into actionable therapeutic targets that can succeed in curing cancer.

Matt Hawryluk and Roman Yelensky, 39, went from sequencing tumors to building personalized cancer vaccines.

Matt Hawryluk, Gritstone Oncology's chief business officer, and Roman Yelensky, chief technology officer, first worked together at Foundation Medicine, a company that's focused on cancer genetics tests. Yelensky joined as employee No. 6 a few years after getting a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in bioinformatics and integrative genetics, while Hawryluk joined after working at Thermo Fisher and getting his Ph.D. in cell biology and biochemistry at the University of Pittsburgh along with an MBA from Carnegie Mellon.

There, the two partnered with pharma companies to conduct research and build diagnostic tests. It was at that point where they got interested in building a company that took genetic information and built it into personalized cancer therapies. By 2015, the two had joined Gristone.

Gritstone's treatment, which is customized based on a person's tumor mutations, is meant to essentially "prime" the immune system. Some people are good at responding to an established class of cancer immunotherapy drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, but others aren't. The hope is that by using the vaccine in combination with the checkpoint inhibitors, you might be able to get more people to respond. The treatments are highly personalized, which Hawryluk referred to as "n of 1" therapeutics for its small sample size. In August, Gristone raised $93 million from investors including GV.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Yelensky said it will be the introduction of new technology into drug delivery, particularly deep learning. Hawryluk said the contribution will be using this technology to bring about speedier drug approvals.

Rachel Haurwitz, 32, wants to transform everything from livestock to medications using the revolutionary gene-editing technology CRISPR.

While doing her Ph.D. at the University of California at Berkeley in 2007, Rachel Haurwitz, CEO of Caribou Biosciences, had the "luck" to work with an exciting new technology called CRISPR. At the time, the revolutionary gene-editing took only had one paper that had been written about it.

The more she learned, the more she realized how much of the technology had the potential to be used not only in academic research but also in everything from therapeutics, to agriculture, to livestock. Haurwitz, along with a team of scientific cofounders including biochemist Jennifer Doudna, a professor at UC Berkeley who was instrumental in early work on CRISPR, created Caribou as a platform tech company.

Through Caribou, partner companies like Novartis and DuPont are able to license CRISPR for use in their products. In addition to external partnerships, Caribou's plan is to also get into some commercial markets as well, or potentially spin out companies, as the company did with Intellia Therapeutics, a company exploring how to apply CRISPR to medicine.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: This generation will be willing to take big bets and be way more comfortable combining science and technology, pushing the field forward, Haurwitz said.

David Giljohann, 36, is developing therapies that could silence mutated genes to treat cancer.

David Giljohann is the CEO of Exicure, a Chicago-based Bill Gates-backed biotech. The company's building drugs built out of RNA that can silence mutated genes that cause diseases like psoriasis or cancer. RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is the instructions cells need to make proteins.

The platform came out of work Giljohann did at Northwestern University, where he got his Ph.D. There, he built spherical structures that look like "Koosh balls" made of nanoparticles and DNA or RNA. The aim is to use the structures to deliver the DNA or RNA directly into cells virtually "anywhere your inside touches your outside," Giljohann said.

So, for example, for psoriasis, a skin condition, the drug is applied on the skin. The hope is that by treating diseases locally, they might work better than a drug that's swallowed or injected and spread around the entire body.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: This generation will be able to design patient-specific drugs that are targeted and faster to develop, Giljohann told Business Insider. Ideally, these new therapies will also be cost-effective, a sticking point for biotech as some drugs start to get $100,000-plus price tags.

Arpa Garay, 38, heads up Merck's $4.5 billion vaccine business.

Arpa Garay recently became the new vice president of vaccines at Merck after spending two years working in Norway as a managing director. During the 10 years she has spent at Merck, she's worked in a range of disease areas from diabetes to cancer.

Now as the head of vaccines, she's overseeing the area during a time when the business model of pharmaceutical companies is experiencing a big change. Garay is tasked with growing the vaccine business, which includes vaccines for human papilomavirus, pneumonia, and chicken pox, among others.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: It'll be by using data better, more efficiently, and having a more global mind-set, Garay said.

Kyla Driscoll, 37, wants to unleash the immune system on some of the most diabolical forms of cancer.

Kyla Driscoll, a senior research adviser and group leader at Lilly, is working to develop new cancer immunotherapy treatments that target TGF-beta, a cytokine (proteins that are important in cell signaling) that suppresses the immune system in seriously hard-to-treat cancers including glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer. The hope is that by finding new ways to target the immune system, more people with these tough-to-treat cancers might be able to use their own bodies to fight cancer cells.

Driscoll got her Ph.D. from Rutgers University, where she studied how viruses can induce cancer and working with cancer vaccines.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: More clinical trials that are more "judicious" about finding people who will respond the best, Driscoll said.

Colleen Cuffaro, 33, is building companies that take new approaches to treat diseases.

Colleen Cuffaro, a principal at Canaan Partners, started her career studying chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania before getting her Ph.D. in cellular and molecular physiology at Yale. During that time, she was introduced to investing and venture capital.

Cuffaro joined Canaan in 2014 and has since led the $38 million investment round for Arrakis Therapeutics, a company that's working on RNA-targeted drugs. She's also the CEO of a small biotech that's still in stealth mode.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: It'll be on focusing on genes, rather than proteins, which is how most drugs work today. "Building on those advances and integrating the chemistry, biology, and computational knowledge that exists today, our generation is thinking outside the (protein) box, if you will," Cuffaro said. "Shifting the focus to modulating genes brings us to entirely different modalities — gene therapy, gene editing, cell therapies, drugging RNA."

Viki Bockstal, 32, is developing vaccines to prevent HIV and Ebola.

Viki Bockstal, the biomarker lead for filovirus vaccines at Johnson & Johnson's Janssen Vaccines, helps develop vaccines to prevent hard-to-treat conditions, including HIV, polio, and Ebola. She joined Janssen in 2012 after receiving her Ph.D. in bioengineering sciences at Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Her job is to help Janssen's Ebola vaccine keep moving through clinical trials, a process that can be difficult when there isn't an Ebola outbreak. In the absence of that, Bockstal determines the parameters that help determine whether the vaccine is effective or not.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Bockstal said it will be by finding vaccines or cures for some of the infectious diseases and conditions that have so far evaded our grasp, such as Ebola, HIV and cancer. "I truly believe this generation has the best shot at not only making this happen, but also really eradicating diseases such as AIDS, measles, polio, tuberculosis, and malaria," Bockstal said.

Jake Bauer, 38, wants to bring back innovation to heart disease.

Jake Bauer, senior vice president of finance and corporate development at Myokardia, was on the premed track at Duke University before realizing that working as a doctor wasn't his calling. Instead, he went into consulting, where he worked with major biotechs before getting his MBA at Harvard. After completing his degree, Bauer joined as the fourth employee at Third Rock Ventures, which invests and helps build biotech companies.

Through his work at Third Rock, Bauer joined Myokardia, a company that's finding ways to treat hereditary heart conditions at a time when the biopharma industry has shifted its attention away from cardiovascular diseases. Myokardia's lead program is a treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy, conditions that make it hard for the heart to pump properly. HCM is the most common genetic cardiovascular disease, and right now, the treatment can be treated with surgery.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: Integrating the best practices from other industries into its business model, Bauer said. It's something he's already taken to heart by hiring people at Myokardia that don't have a traditional biotech background.

Stephanie Barrett, 36, is building implantable devices to help treat HIV and other infectious diseases.

Stephanie Barrett, a principal scientist at Merck, is working to make implantable devices to treat infectious diseases. Originally from Canada, Barrett moved to the US in 2004 to get her Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Shortly after completing her graduate work, she joined Merck.

Right now, treatments for diseases such as HIV and hepatitis are taken via pills. Merck's hope is that by building an implanted device, people will do better on the medications because they will actually adhere to them. Adherence is key when you're thinking about infectious diseases like HIV where you need low viral counts.

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: The energy and "hungriness" this generation will have will propel things forward, Barrett said.

Aris Baras, 33, is on the hunt for blockbuster drugs linked to our genes.

Aris Baras, vice president and head of the Regeneron Genetics Center, joined Regeneron after getting an M.D. and an MBA at Duke University. During his time in North Carolina, he did his research in immunology and biology. What drew him to Regeneron was its approach of using genomic information when discovering and developing drugs.

Using its genetics center, which Baras has been head of for four years, Regeneron has had success in getting drugs with a genetic component approved. That includes Praluent, a drug to treat high cholesterol that inhibit PCSK9, a protein encoded by the PCSK9 gene, and Arcalyst, a drug that inhibits the IL-1 receptor to treat certain rare diseases.

The hope is to do that for all drugs Regeneron's working on from here on out.

"We’ve been trying to do it with the whole pipeline," Baras said.

Narges Bani Asadi, 36, wants to make human-genome analysis more useful to people.

Narges Bani Asadi, the vice president and Life Cycle Leader of sequencing genomics at Roche Sequencing Informatics, grew up in Iran before moving to Stanford University for graduate school. While pursuing a master's and later a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, she met a mentor who explained to her a future in which biology and medicine is more about data than a biology or chemistry lab problem. "It blew my mind," she said.

From there, she started working at that intersection between computer science and medicine, launching a startup called Bina that was later acquired by Roche. The company worked to find clinical applications for genomic data, so that the findings that come out of academic researchers make it to patients.

"How can that actually change medicine? That's the bottleneck today," she said. "What is the clinical utility of this information?"

The contribution the under-40 generation will have on medicine: It will be getting more nontraditional, and possibly even younger people into the industry that come from different backgrounds and expertise areas, Bani Asadi said.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement