I learned the meditation technique taking over Wall Street and now I get why traders are willing to set aside 40 minutes a day

The David Lynch Foundation's New York center is located on the 14th and 15th floors of a building in midtown, Manhattan.

Lynch, the acclaimed director ("Twin Peaks," "Mulholland Drive"), cofounded his foundation in 2005 with the intention of teaching TM for free to disadvantaged students, veterans with PTSD, and victims of domestic abuse.

Through partnerships with middle and high schools in the US, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and shelters, the DLF has taught TM for free to 500,000 people.

Veterans can also take lessons at the DLF office, as one did during one of my trips.

On my first visit, before my lessons began, I sat down with DLF teacher Mario Orsatti and DLF cofounder and executive director Bob Roth.

They're best friends of 40 years, and were fun to talk to — not at all the terrifying cult leaders I was afraid they might be.

As they put it, TM is a simple but effective technique. The $960 fee offers lifetime access to all TM centers and teachers across the world, and it funds operations and the modest teacher salaries (roughly $40,000-$80,000) that allow them to teach people for free. If people seek out TM and cannot afford it, they can apply for scholarships.

I returned for my introductory lesson two weeks later, on a pleasant fall Friday, late in the afternoon.

Roth and Orsatti offered me lessons with a fee waiver, as they had done with other journalists, so that I would have more context for my research.

I stopped off at the bodega down the street from the DLF office to buy some fruit and irises for the "traditional ceremony" I'd be participating in. I felt like I was about to step into one of Lynch's surrealist films.

Orsatti had me take my shoes off and we walked into a darkened room.

He led me to a corner, where there was a small altar with an illustration of Brahmananda Saraswati, also know as Guru Dev ("divine teacher"). Guru Dev was the teacher of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of TM, and we were there to honor him before learning the technique.

Orsatti handed me one of the irises and began solemnly reciting what I assumed to be a Sanskrit prayer. He proceeded to light candles and arrange the fruit and other items before him. I found it interesting, but I wouldn't figure out what was actually happening until weeks later.

I was a little skeptical.

But I didn't let myself off the hook! I allowed for the possibility that I was about to learn a valuable meditation technique ... even if it did seem a little cult-like.

At the end of the ceremony, Orsatti turned to me and declared a meaningless "vibration word" that I recognized as my mantra, and I repeated it back to him.

We sat down in sofas at either side of the room and began meditating.

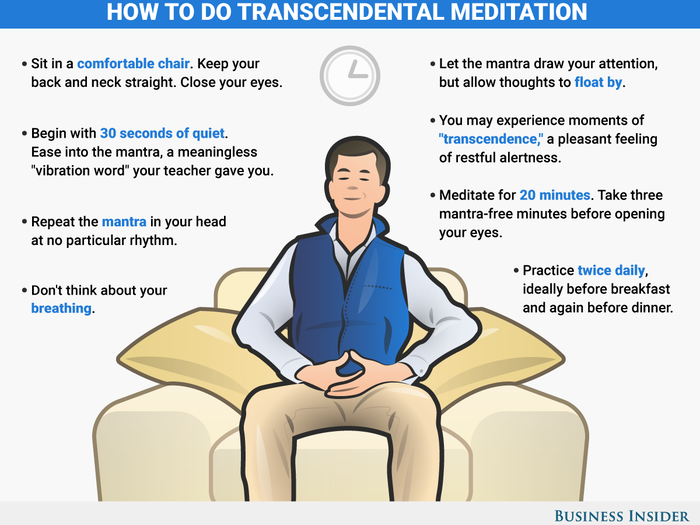

The technique itself is simple, consisting of sitting upright in a chair, closing your eyes for 20 minutes, and repeating a mantra — a meaningless "vibration word" provided by your teacher — in your head at no particular rhythm. It is recommended that one practice this twice daily, once in the morning and once in the evening.

For most people, including myself, TM is easy to learn but takes a couple weeks to practice naturally. It's why your TM teacher checks in for a few followup lessons after the initial four-day introduction.

My first meditation felt good.

This wasn't my first time meditating. Before this, I had spent eight months practicing mindfulness meditation (focusing on breathing and directing thoughts to certain images or ideas) for 10 minutes daily, through the app Headspace.

It reminded me of my favorite aspects of meditations past, and I enjoyed the 20-minute duration, which was the longest I had ever meditated. The feeling of "transcendence" — which you get during especially good meditation sessions but not all — was familiar, and the feeling I had always gone for with other meditation techniques I had tried.

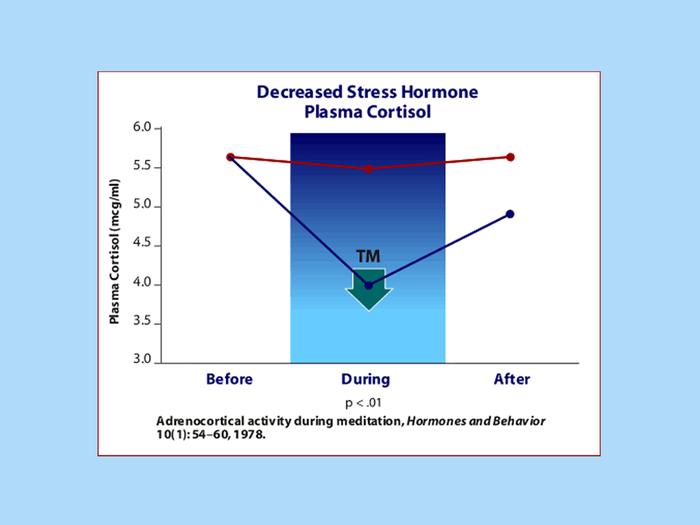

As a side note: If you think meditating is like taking a nap from a seated position, you're doing it incorrectly. There is also years of peer-reviewed research that proves that the brain differentiates between sleep/dozing and meditation, and that meditation can quickly rid the body of stress-inducing hormones.

I had three more days of training that week, to refine the technique.

For example, I learned that if particularly stressful thoughts went through my head, it's helpful to stop repeating the mantra and let the thoughts float away before resuming it.

"Imagine yourself sitting by a busy highway," Headspace cofounder Andy Puddicombe says in one of his lessons. "Cars continue to pass by. You can choose to sit there and notice the cars without focusing on any of them, or you can follow a car down the road."

It's the same with mindfulness meditation and TM. As you sit there with eyes closed, all kinds of thoughts may be flying through your mind. Instead of exerting energy to try to block them, which often backfires and makes the mind more cluttered, focus on breathing (mindfulness) or the mantra (TM), acknowledging that they exist without engaging them.

I still had many questions about the organization behind TM.

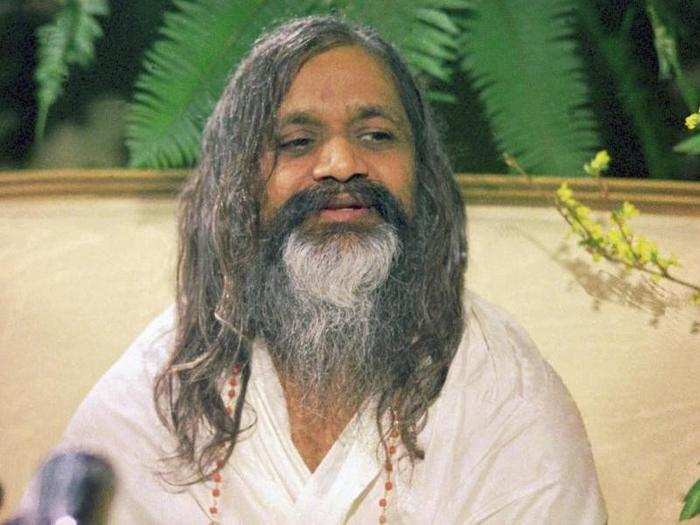

The best place to start finding answers was with the late Maharishi, the founder.

In training classes, we were shown videos of the Maharishi (a title that means "seer"), a small man with long wispy hair, a scraggly beard, a high-pitched voice, and a penchant for giggling. As I learned more about him, my perception of him transformed from potential cult leader to one of several Indian philosophy teachers who introduced Westerners to their ancient traditions during an immigration wave in the early to mid-20th century.

Born in India as Mahesh Prasad Varma in 1918, he renounced his name and familial ties in typical Hindu monk fashion after graduating from Allahabad University in 1942 with a physics degree and traveling to Jyotir Math in the Indian Himalayas to study under and serve Swami Brahmananda Saraswati, the man he reverentially called Guru Dev.

Saraswati was the leader of the city's monastery, a lofty position within the religion. When the Maharishi began his global tour of spreading TM in 1958, he made it clear that although he and his guru were Hindu monks and TM was rooted in the ancient Vedic scriptures, his practice was not tied to the Hindu faith.

One of the exceptions he made, however, was that TM teachers would perform a puja to Guru Dev in front of their students before an introductory lesson — that same ceremony with the fruit that made me uncomfortable on my first day. After learning more about the ritual itself and the Maharishi's intention to honor his teacher out of tradition, I was willing to accept this remnant of religion in a deliberately secularized practice.

I discussed this with Orsatti at one of our follow-up meetings, and he told me that the Maharishi wanted to share this insight without restraining it to religion in any way. The highest aim of TM, then, is to make people more able to connect with others by having them be more in touch with themselves.

In mid-October, after nearly 10 months of meditating, I went for my annual physical.

I told my doctor that I had been meditating for almost a year, first with mindfulness meditation, and then with TM. She said that there was a solid chance that it was a reason why my blood pressure was normal rather than moderately high for the first time in five years. She also told me she and other doctors she knows have recommended TM to patients due to the research out there from organizations like the American Heart Association and the University of California, Irvine.

I was still left with a major question.

TM has spiritual roots but has also always been touted as a tool for healthy living. Were the two compatible, or was the TM organization being disingenuous?

I discussed this dynamic with Suhag Shukla, executive director of the Hindu American Foundation, and while she has separate gripes about the general lack of understanding many Americans have of Hinduism's affect on popular culture, she said promoting meditation as part of a healthy lifestyle is actually authentic to its roots.

You can understand the Vedas, she told me, as "scientific experiments of the mind," and so analyzing an ancient technique with the lens of modern science isn't a deceptive dilution.

I've decided to continue practicing TM every day, for the recommended 20 minutes in the morning and 20 minutes at night.

I'm fully aware that I received $960 of training for free, and therefore I'm unable to comment on whether I can recommend someone pay that, or at least apply for a scholarship.

For what it's worth, Bob Roth of the David Lynch Foundation told me he's been working to get TM lessons covered by insurance plans, given the accumulation of research in its favor, and he's hopeful it'll happen.

As for me, I'm going to continue practicing TM twice a day.

I use the app Meditation Timer, which I've set to chime after 20 minutes have passed, and again after the recommended two-minute "rest period" elapses. The extra two minutes help me ease back into a normal state, especially after a deep meditation.

I'm a naturally anxious person, and meditating for the past year has improved my mood enough that my family and friends have told me they've noticed. Mindfulness meditation can do the trick, but I've decided to continue practicing TM due to its simplicity.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement