- Home

- entertainment

- news

- The biggest unanswered questions we still have after watching Netflix's 'This Is A Robbery'

The biggest unanswered questions we still have after watching Netflix's 'This Is A Robbery'

Debanjali Bose

- In 1990, artwork worth $500 million was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

- A new Netflix series, "This Is A Robbery," takes a closer look at the massive heist.

- But we still have questions after watching the four-part series, like where the stolen art wound up.

Who robbed the museum and what exactly did they do with all of the art that was stolen?

Netflix's latest addition to its ever-growing true-crime collection, "This Is A Robbery: The World's Biggest Art Heist," centers around the infamous 1990 burglary at Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Art collectively worth $500 million went missing that night.

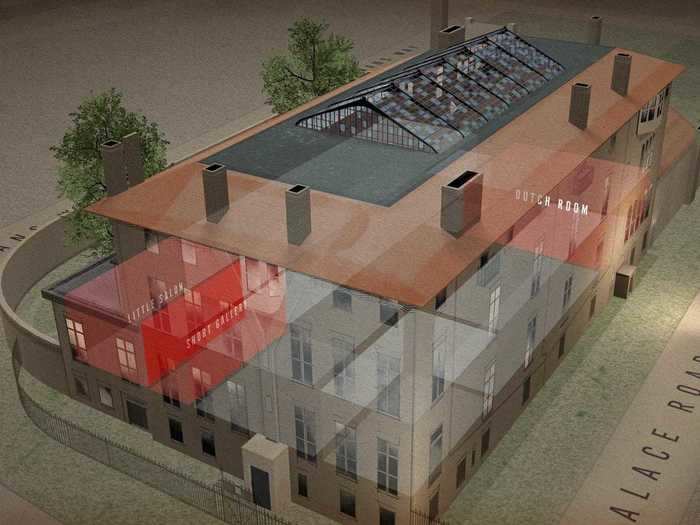

Two people dressed in Boston police uniforms slipped into the museum in March 1990, tied up the guards on duty, and stole 13 pieces of art over a span of 83 minutes.

"This Is A Robbery," a four-part documentary series, breaks down the heist sequence-by-sequence through animations, recreations, and interviews with journalists, law enforcement, and eyewitnesses.

The docu-series never reveals who actually carried out the infamous robbery, as no one was every arrested for the crime, though several theories are laid out for viewers.

The filmmakers highlight a crew of seven people with ties to the Italian mob in Boston as possible perpetrators, theorizing that the heist was planned out by two men named Bobby Guarente and Bobby Donati and that two people from their crew, David Turner and George Reissfelder, may have went into the museum to steal the art for use as leverage in future legal or law enforcement battles.

The documentary also reports that the art may have changed hands a few years later and ended up with Bobby Gentile, a known associate of Guarente.

All this remains unconfirmed, and although the FBI announced in 2013 that they knew who was behind the heist, the federal agency didn't publicly reveal any names.

The art that was lost during the robbery, dubbed "the biggest art heist in the world" by the documentary, remains missing 31 years later.

While there is no conclusive information about what happened to the paintings and artifacts, the four-part series offers a few theories and anecdotes about people possibly having spotted it over the years.

One such anecdote in the documentary comes from Reissfelder's sister-in-law, Donna.

In the third episode, Donna said that a few months after the heist, she helped Reissfelder hang the Chez Tortoni by Manet, one of the missing art pieces, on his bedroom wall. Reissfelder died in 1991, according to the documentary.

Donna said she didn't know that the painting was a highly sought-after piece of art until years later when people from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum contacted her about the stolen collection.

In the same episode, journalist Stephen Kurkjian said that a surveillance camera from 1991 might have caught Turner leaving his car with an object that looked like a 12th-century vase that also went missing during the heist.

In the final scenes of the series, various journalists, law enforcement officials, and one former art thief theorize that the art might have been destroyed under pressure from all the scrutiny, been shipped outside the US, or stashed away.

But in the end, viewers don't really know what happened to the art or who took it — and the public may never know.

Why did the people behind the heist pick those specific pieces of art?

The art that was stolen included works by some of the most renowned painters in the world, like Rembrandt, Édouard Manet, Johannes Vermeer, Edgar Degas, Govaert Flink, as well as some artifacts.

The documentary series raises some questions about why the people behind the heist made certain choices regarding what artwork to take.

Former FBI official Tron Brekke, who was involved in investigating the 1990 robbery and is featured in the series, believes that the robbers had "either cased the place or been given specific information about what to look for."

One of the pieces that went missing was Gu, a vase-shaped Chinese artifact from the 12th century. In the documentary, former assistant US attorney Robert Fisher questioned why the thieves picked that vase over some of the other, far more valuable artwork in the room.

"It's old, it's somewhat valuable, but not even close to some of the other items of art just in that room," Fisher said of the vase.

Even more bizarrely, the thieves also stole a postage-stamp-sized Rembrandt etching after removing it from its similarly-sized frame.

"The frame it was in wasn't much bigger. And yet somebody wasted time unscrewing that and then taking apart the whole frame and taking only the etching," Fisher said.

"If you're carrying out the biggest heist in history," he continued. "And you don't know if the police are coming, and you have limited time to get the most valuable artwork, are you going to waste time with an etching that isn't even that expensive?"

"And waste precious moments taking it out of a frame that you could probably stick in your pocket?" Fisher added.

As of April 2021, the museum is offering a $10 million reward for any substantial information about the 31-year-old heist.

What happened to the tape that was used to tie up one of the guards?

"This Is A Robbery" reports that the people behind the heist entered the museum through the main entrance while pretending to be policemen. They then tied up the two on-duty guards before gathering up the art they would steal.

The series spends a full minute of the first episode dissecting the manner in which one of the guards, Richard Abath, was tied up while the robbery took place.

The robbers placed duct tape around Abath's eyes, nose, and the front of his face. This has raised some eyebrows amongst experts.

"And then his hands were bound, which I thought was kind of odd," John Green, a former FBI image analyst who was interviewed for the docu-series, said of the duct tape around Abath's hands. "They had a little pad."

"Why would you tape him all around the head?" he continued. "Why not just put tape on his eyes? I've seen people who were killed, were taped. But Rick's taping — I never saw anything like that."

During his documentary appearance, Green also questioned why the robbers behind the heist didn't simply kill Abath to avoid having a witness to their activities.

"Dead men tell no tales," he added.

Moreover, the documentary notes that the tape that was used to tie up Abath, which potentially contained the art thieves' fingerprints, went missing during the investigation.

Why didn't the alarm go off in a room that was robbed?

Former assistant US attorney Robert Fisher said in the series that all of the security systems put in place at the museum were working properly the night the robbery took place.

"The system had been reviewed by security experts right after the robbery," he said. "Experts that are still around today in the industry, and are well-respected, and claimed it was working as it should have the night of the robbery."

Museum-security consultant Steve Keller confirmed in an interview for the series that he had done a walkthrough of all the alarms at the museum after the robbery in 1990 and they were all working fine.

However, the last person detected by the motion sensors in a room that was robbed, the Blue Room, was Abath (who was ruled out as a suspect by Fisher), about an hour before the people behind the heist entered the museum.

While there were no alarms inside the Blue Room itself, it is unclear how the burglars were able to steal a Manet painting from that room without setting off motion detectors in the doors on either side of it.

Where did the 17th-century paint chips produced by a separate art thief (not one of the people behind the Gardner heist) come from?

About twenty minutes into the third episode, the documentary series explores a once-seemingly viable lead into recovering the lost art.

The series reports that a petty criminal by the name of William Youngworth, who worked with noted art thief Myles Connor (who is also interviewed in the documentary), said he had "information that could lead to the recovery of the Gardner art" while trying to negotiate some criminal charges.

To bolster his claims, Youngworth took former Boston Herald journalist Tom Mashberg to a warehouse in Brooklyn, New York, where Youngworth showed the reporter what looked like Rembrandt's 17th-century "The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee" (one of the 13 pieces of artwork that were stolen).

While Mashberg acknowledges in the documentary that he's not an art expert and he wasn't sure if it was the real thing, he said it seemed "very plausible" to him "that the stolen art was stored here at least temporarily."

Mashberg said that he discussed the story with the museum curator and head "for a long time."

Anne Hawley, director emerita of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, pointed out in the documentary that the paintings are centuries-old and need to be stored flat, so as to not destroy the paint, while the painting Youngsworth showed Mashberg came from a tube.

Youngworth also shared paint chips with Mashberg that were analyzed by renowed chemist Walter McCrone.

"I felt as though I was looking at something that Rembrandt has produced, and it looked like the paint layers and the pigment that was produced in Holland at the time," McCrone said of the paint chips in archival footage included in the series.

"Everything was just perfect for a Rembrandt paint layer. I have never experienced this before," he added.

But not so fast: Despite McCrone's assurance that the paint chips were produced in the right time period, the color didn't match the painting the chips had supposedly come from.

"They may be chips from the 17th-century, but if the color doesn't match the colors in the painting, then they can't come from one of those paintings [that were stolen]," Mashberg said in the documentary series.

While the series concludes that it is unlikely the paint chips were a part of the stolen "The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee" by Rembrandt, it's unclear what 17th-century artist or painting the paint chips actually came from — or how Youngworth came to have them.

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement