- Home

- entertainment

- news

- 17 moments in Disney movies that haven't aged well

17 moments in Disney movies that haven't aged well

Abby Monteil

- Disney films have been a mainstay in many people's childhoods for generations, but some elements of them don't hold up today.

- For instance, there are racist caricatures in "Dumbo" and "Lady and the Tramp," and non-consensual kisses in "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" and "Sleeping Beauty."

- Here are 18 moments in Disney movies that haven't aged well.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

Since "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was released in 1938, the fantastical worlds of Disney's children's films have captivated generations and become a mainstay in many people's childhoods. However, it's undeniable that some elements of Disney movies (especially older ones) simply don't hold up well today — specifically in regards to how they treat women, people of color, and queer people.

In fact, when the streaming service Disney Plus (which includes almost every Disney movie) launched in late 2019, a message was included ahead of classic movies like "Dumbo," and "Peter Pan," warning that the movies "may include outdated cultural depictions."

From the racially stereotyped crows in "Dumbo" to the central kisses in "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" and "Sleeping Beauty," here are 17 moments and themes in Disney movies that haven't aged well.

Read the original article on InsiderMany people view Disney villains as queer-coded, enforcing negative homophobic tropes.

Queer-coding is when writers consciously or unconsciously include stereotypes about LGBT people as characteristics of a character without their sexuality being part of a broader story. Typically, queer-coded male villains tend to be effeminate, flamboyant, and/or talk with a lisp, while queer-coded female villains tend to be more masculine and brash than the movies' heroines.

Some people argue teaching young viewers to unconsciously associate stereotypical queerness with villains can have a harmful effect on how they view and associate with members of the LGBT community.

"From a very early age, we're conflating queerness and gender expression outside of the binary with evil and villainy, especially with no counterpoints due to the total lack of positive and canonical queerness in children's media," argues YouTuber Rowan Ellis in her video essay "Why Are Disney Villains Gay/Queer?"

A few examples of Disney villains people believe are queer-coded include Scar from "The Lion King," Jafar from "Aladdin," Hades from "Hercules," King Candy from "Wreck-It Ralph," and Ursula from "The Little Mermaid."

Many of Disney's lead characters of color are transformed into animals for the majority of their stories.

"The Princess and the Frog's" Tiana, "The Emperor's New Groove's" Kuzco, and "Brother Bear's" Kenai all have one thing in common — they're main characters of color in Disney movies who spend almost all of their respective stories physically transformed into animals.

A version of this trope seems to appear in the upcoming Pixar film, "Soul," in which Joe Gardner (the black main character) is separated from his body and appears as a teal mass (meant to be his "soul") for what seems like most of the story.

By disproportionately turning people of color into animals and other entities in their films, fans argue Disney doesn't allow them to learn and grow in their human forms like nearly all of the studio's white characters.

"It feels like the characters seemingly have to be transfigured in some form for the writers and animators, mostly white men, to be able to truly care about them," wrote Monique Jones for Shadow and Act. "Is this because the animation field, a field that still has work to do in terms of having racial parity in the workplace, doesn't know how to successfully write about non-stereotypical characters of color?"

People said the treatment of the hyenas in the original "Lion King" was racist.

In 1994's "The Lion King," Scar's accomplices are three hyenas — Shenzi, Banzai, and Ed. Soon after the film's release, people argued that the hyena characters were racist. The two hyenas who speak are voiced by actors of color (Whoopi Goldberg and Cheech Marin) in a predominantly white voice cast, they speak in slang and serve a leader who speaks British English, are weak-willed and dim-witted, and come from the unsafe, "shadowy" area where the movie's young protagonist isn't allowed to go.

Ed, the third hyena, doesn't talk, but cackles and spasms in a way that was reminiscent to some of Tourette's Syndrome.

"The hyenas transparently represent the black, brown, and disabled bodies that are forcefully excluded from this hierarchical society," Dann Hassler-Forest wrote in The Washington Post. "Noticeably marked by their ethnically coded 'street' accents, the hyenas blatantly symbolize racist and anti-Semitic stereotypes of 'verminous' groups that form a threat to society."

In the 2019 remake of "The Lion King," the hyenas are much shrewder and more threatening.

"The hyenas had to change a lot," said Jon Favreau in Disney's press notes for the new movie. "Because of the photo-real nature of the film, having too broad of a comedic take on the hyenas felt inconsistent with what we were doing."

The opening song in "Aladdin" originally included anti-Arab lyrics.

In the original theatrical version of "Aladdin," a line from the opening song, "Arabian Nights," goes, "Where they cut off your ear, if they don't like your face / It's barbaric, but hey, it's home."

Disney replaced the first half of those lyrics in all future versions of the movie after facing backlash from the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, but refused to cut, "It's barbaric, but hey, it's home."

"To characterize an entire region with this sort of tongue-in-cheek bigotry, especially in a movie aimed at children, borders on barbaric," The New York Times said of the song in 1993.

In the 2019 live-action remake, the lyrics were once again changed, this time to "Where you wander among every culture and tongue / It's chaotic, but hey, it's home."

In "The Little Mermaid," Ariel gives up her voice and entire life for a man she's never officially met.

It's never a good idea to give up your voice or sense of self for a romantic partner — especially when you're 16 and your potential love interest is a man you've never officially met. But Ariel literally does just that in 1989's "The Little Mermaid," showcasing an unhealthy view of relationships and romance to young women in particular.

As Ursula tells Ariel when she agrees to give up her ability to speak in order to become human and vie for Prince Eric's affections, "On land it's much preferred for ladies not to say a word / It's she who holds her tongue who gets a man."

"To make matters even worse, the little mermaid's voice is her most cherished talent," wrote Simone Torn for Screen Rant. "She loves singing more than anything but she won't be able to do that anymore because she has to make things work with the first dude she sets her eyes on."

"Pocahontas" romanticizes and skirts over the atrocities committed by Europeans against Native Americans.

In Disney's 1995 film "Pocahontas," the love between the movie's titular Native American protagonist and John Smith (a white Englishman sent to help "settle" America) effectively puts an end to the conflict between their two communities.

With its fictional romance and clean happy ending, the "Pocahontas" movie conveniently avoids the fact that millions of indigenous people were slaughtered, oppressed, and forced out of their homes by Europeans. As a result, it effectively erases their historical actions and paints a whitewashed picture of some of the darkest moments in American history.

"I've struggled with Disney's 'Pocahontas' as a source of pain and stereotype," Kenzie Allen, a descendant of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin, told The Atlantic. "[...] Yes, there is visibility in telling their stories, but it is a tainted visibility, a false reality rendered through the dominant culture, which seeks to ameliorate, always, the horrific methods by which they came to occupy an entire nation's worth of landmass."

Belle teaching the Beast to be a good man in "Beauty and the Beast" sends questionable messages about relationships to young women.

The central question posed at the beginning of "Beauty and the Beast's" opening monologue is, "Who could ever learn to love a beast?"

That person turns out to be Belle, the bookish protagonist who teaches the cruel, abrasive Beast to be considerate and kind enough to transform back into a prince at the 1991 movie's end.

Unfortunately, this plot sends young girls the message that they can "fix" men who exhibit frightening and even abusive behavior towards them, and that it's up to them to fix those men in the first place — a message that isn't altered in the 2017 live-action remake.

Some even argue that Belle is showing signs of Stockholm Syndrome, in which hostage victims develop feelings of trust or affection toward their captors.

"Under this reading, when Beauty at last tells the Beast that she loves him, it doesn't feel like a genuine romantic decision made by a fully empowered woman under her own free will," wrote Constance Grady for Vox. "It feels like the culmination of a whole story's worth of emotional abuse and grooming."

In 1967's "The Jungle Book," King Louie and his subjects can be interpreted as anti-black caricatures.

One of the most well-known characters from Disney's "The Jungle Book" is King Louie, an orangutan who is "king of the apes" and famously tells Mowgli, the human protagonist, "I wanna be like you."

The concept of an ape wanting to be like a human is innocent enough, but the movie's use of Louie becomes more concerning when viewers realize that the character and his subjects are the only characters who speak in jive slang. Every other character speaks in British English, implying that the "Jungle Book" apes embody historically dehumanizing, racist comparisons between black people and apes.

In the 2016 live-action remake of the film, King Louie is not an orangutan, but a gigantopithecus (a now-extinct primate native to the Indian jungle where "The Jungle Book" is set). Voiced by Christopher Walken, he forgoes any jive associations and is much more menacing towards Mowgli.

The "Aristocats" also features a Siamese cat who embodies crude Asian stereotypes.

The Siamese cat Shun Gon, who appears in 1970's "The Aristocats," isn't much of an improvement on Si and Am. He plays the piano with chopsticks, speaks in a stereotypical accent, and sings about fortune cookies.

The Siamese cats in "Lady and the Tramp" are racist caricatures of Asian people.

In 1955's "Lady and the Tramp," the character Aunt Sarah has two Siamese cats named Si and Am, who sing "The Siamese Cat Song." With their bucked teeth, slanted eyes, and stereotypical East Asian accents, they're racist caricatures. The cats' entrance is even marked by the sound of a gong.

"Si and Am of 'Lady and the Tramp,' which premiered just a decade after the [World War II's] end, were undoubtedly conjured by the remaining prejudices of this milieu, emblems of an era when anything categorically or characteristically 'Asian' was met with misplaced fear," wrote Marcus Hunter for Flavorwire.

Luckily, in the 2019 live-action remake of "Lady and the Tramp," Si and Am are replaced by cats of a completely different breed. The film's music collaborators, Nate "Rocket" Wonder and Roman GianArthur, voice them, and they sing a new song called "What A Shame."

The Native Americans in "Peter Pan" are stereotypical and feature cultural appropriation.

In 1953's "Peter Pan," Peter's friend Tiger Lily belongs to a Native American tribe that he and the Darling siblings visit at one point in the film. The depiction of Native American culture is homogenous and stereotypical: The characters speak in gibberish instead of an actual indigenous language, smoke excessive amounts of pipe tobacco (which they even offer to the children), and sing an offensive song called "What Made the Red Man Red."

"Lumping all American Indians together as one monolithic caricature is grossly offensive, because these are real people, with many, many different cultures," wrote Elizabeth Broadbent for The Huffington Post.

Peter and the Darlings also appropriate the tribe's culture, wearing headdresses, brandishing tomahawks, and making stereotypical "whooping" noises.

This one-note, demeaning depiction of Native Americans, as well as the cultural appropriation at play, would likely be cut by today's standards.

Child trafficking occurs multiple times in "Pinocchio."

If you haven't watched 1940's "Pinocchio" in a while, you might mainly remember the movie for its lovable titular puppet and the song "When You Wish Upon a Star." But you may have forgotten the story's darker, more disturbing elements, particularly the sheer amount of child trafficking that takes place.

The morning after Pinocchio is brought to life, two strangers convince him to skip school and sell him to Stromboli, a puppet master who threatens to chop the boy into firewood if he doesn't perform for him in a life of servitude.

Once Pinocchio escapes, he's almost immediately carted off to Pleasure Island, where badly behaved boys drink, smoke, and generally wreak havoc. However, every child who participates in the island's activities is then turned into a donkey and sold to work in nearby salt mines.

With the recent news of a "Pinocchio" live-action remake moving forward, it's likely that these two plot points will be modernized.

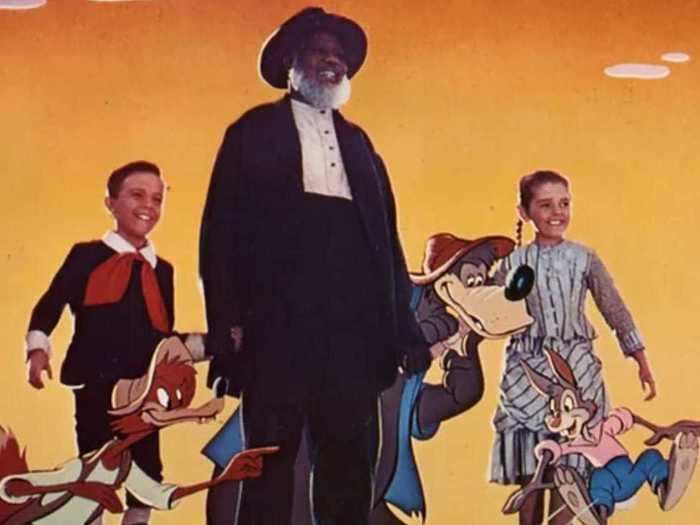

Every moment of "Song of the South" is offensive.

You might be familiar with the Disney theme park ride "Splash Mountain" or the song "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah." But if you're unfamiliar with "Song of the South," the 1946 Disney movie that they come from, you're not alone — it's been locked away in the Disney Vault for decades, and is considered the company's most offensive release.

"Song of the South" is set on a 19th-century southern plantation and follows Uncle Remus (James Baskett), a black former slave who lives happily on his former white master's plantation. The movie's rosy portrait of slavery and racial relations in the South immediately drew criticism at the time of the film's release.

"In an effort neither to offend audiences in the North or South, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery … ['Song of the South'] unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship, which is a distortion of the facts," the NAACP said in a 1946 statement.

Speaking of Dumbo, he gets drunk in the original 1941 film even though he's a baby elephant.

It seems unlikely that Disney would show children drinking in one of their new releases today, but older animated films depict exactly that.

In one scene from the original "Dumbo," the elephant's friend, Timothy Q. Mouse, tells him to drink a barrel of alcohol that he thought was water. Both animals get drunk in a controversial moment that involved dancing pink elephants.

Disney wisely avoided recreating this scene in the "Dumbo" remake, but they cheekily reference it. In a scene where Dumbo is being bathed, a clown runs in with a bottle of champagne and the ringmaster protests, "Hey, no booze near the baby."

The crows from "Dumbo" reference Jim Crow laws and portray anti-black stereotypes.

In 1941's "Dumbo," the elephant encounters a pack of crows who are some of the only characters who are friendly towards him in the movie.

Today, many believe the crows to be racist caricatures of black Americans for their use of "jive talk." The lead crow is even named Jim Crow in an obvious reference to the racist Southern segregation laws that lasted until the mid-1960s. The character Jim Crow was also troublingly voiced by a white actor (Cliff Edwards).

"Dumbo" also includes a song called "Song of the Roustabouts," in which faceless black circus "workers" sing offensive lyrics like "We slave until we're almost dead / We're happy-hearted roustabouts" and "Keep on working / Stop that shirking / Pull that rope, you hairy ape."

On Disney Plus, Disney has since added a disclaimer to "Dumbo" that said the movie contains racist stereotypes. The 2019 live-action remake of the film also excludes both of these elements, opting to focus on a newly introduced family of circus workers (led by Colin Farrell).

A similar kiss occurs at the climax of "Sleeping Beauty."

Much like "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," the 1959 film "Sleeping Beauty" also includes a pivotal scene where a man kisses an unconscious woman. In order to wake Princess Aurora from the eternal sleeping curse that the villainous Maleficent's spinning wheel has placed her under, Prince Phillip gives Princess Aurora "true love's kiss."

"Sleeping Beauty" is actually derived from a darker Italian fairytale by Giambattista Basile called "Sun, Moon, and Talia," which is based on a folk tale dating back to the 14th century. In this iteration of the story, a king rapes and impregnates the sleeping princess, then marries her after she wakes up.

The 2014 film "Maleficent," which is told from the villain's point of view, attempts to resolve the problematic scene by focusing on the untold story of Maleficent's eventual bond with Aurora. In this film, she kisses an unconscious Aurora on the cheek, and her maternal love for the girl is what causes her to wake up from the curse.

The iconic kiss in "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is non-consensual.

One recurring theme in early Disney princess films is the power of "true love's kiss." In the 1937 film "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," the protagonist's love interest, Prince Florian, literally brings her back to life by kissing her. However, since Snow White is unconscious and essentially dead during the scene, this kiss could be viewed as non-consensual and an act of assault.

Many parents (including celebrities) have voiced their concerns over sharing the scene with their children.

"Don't you think that it's weird that the prince kisses Snow White without her permission?" actress Kristen Bell recalled asking her young daughters in an interview with Parents.com. "Because you can not kiss someone if they're sleeping!"

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement