- Home

- Military & Defense

- What it's really like to be a NASA astronaut

What it's really like to be a NASA astronaut

The hiring process is extremely selective.

Once hired, you're required to go through two and a half years of general training.

A few months after he was selected as an astronaut candidate in 2009, Lindgren began the required two-and-a-half years of general training at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

His hours were like a normal workweek: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., five days a week.

He learned how to do a space walk, operate a robotic arm, respond to emergencies, and conduct experiments in space.

Next, you get assigned to a mission and go through two additional years of mission-specific training.

After completing his general training in 2011, Lindgren and the other 13 members of his class were dubbed active astronauts and assigned to a mission.

Lindgren was assigned to Expedition 44/45 to the International Space Station (ISS) — set to launch in July 2015 — and then began two additional years of mission-specific training.

Unlike the two years spent at the Johnson Space Center, 40% of this second round of training took place overseas at partner training centers in Germany, Russia, and Japan. While there was some classroom time, Lindgren says the majority of their training took place in various space simulators and mockups.

In the last two weeks before launching, the astronauts fly to the Integration Facility at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, where the rocket launch facilities are located, for final dress rehearsals.

They spend this time in quarantine to make sure they don't carry any illnesses up to space with them.

On the official launch day, they wake up, eat a meal, suit up, and walk out to the rocket.

A typical day in space involves some routine tasks and tons of research.

Lindgren says this is what he did on a typical day in space:

6 am: Wake up and attend to basic hygiene, eat breakfast, and review the day's plan.

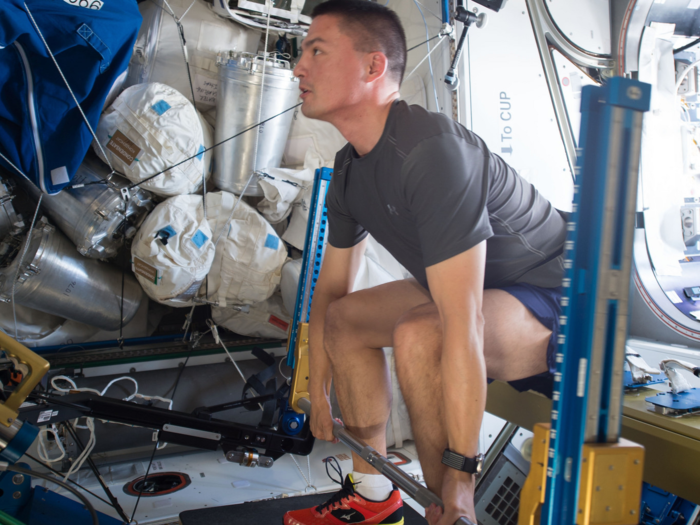

8 am - 7 pm: Do preventive or corrective maintenance to space station systems; do one hour of aerobic exercise on the cycling machine or treadmill; do one-and-a-half hours of resistance training using the ARED (advanced resistance device), which provides resistance up to 600 pounds; eat lunch; and conduct scientific research and experiments.

7 pm: Join evening conference to talk about the day's accomplishments and the plan for the following day.

8 pm - 10 pm: Eat dinner; engage in personal activities, like sending emails, taking photos, and making phone calls.

10 pm: Go to bed.

Life in space is strange — and sometimes difficult.

Lindgren talks about some of odd aspects and challenges of being in outer space.

For instance, to go to bed, you have to get into your sleep pod and zip up your sleeping bag that's tethered to the wall, as demonstrated by Chris Hadfield in this video.

Most astronauts strap the sleeping bag tight against the wall to give the sense of pressure against their back as though they were sleeping in a real bed back on Earth. Lindgren found this uncomfortable so he tied just one tether lightly to the wall and says it "felt like sleeping on a cloud."

He says you also undergo physiological changes.

When you stand up on Earth, all of your blood wants to rush from your head and chest to your legs — but a number of physiological mechanisms prevent that. However, in the absence of gravity in space, most of your blood goes to your chest and head so you feel a "kind of head fullness and a congestion and your face looks puffy and your legs look like bird legs," he explains.

Behavioral psychologists help the astronauts feel at home in outer space.

Some astronauts feel a separation when they see the Earth from space, Lindgren says, but he never experienced that. "I really enjoyed when we flew over places where I knew I had family and friends," he says. "It was comforting to me."

But NASA takes precautions by employing behavioral psychologists, whose job is to protect the astronauts against feelings of depression or separation.

For Lindgren, the hardest part of his job was being away from his family. But the psychologists provided him with technology to call home whenever he had Internet access — which was about 80% of the time he was in space. He ended up being able to call his wife and three kids every night, in addition to a once-a-week video call for an hour and a half.

The psychologists also provided movies to help them relax.

"It might sound a little extravagant, but it's very important when this is the place where you're living and working for an extended duration," he explains. "You're looking for some of those same comforts that you found back at home."

His team watched 'The Martian' in space and said it was surprisingly accurate.

One of the movies they watched in space was "The Martian" — a movie about an astronaut who gets left behind on Mars — and Lindgren said he was impressed with the its portrayal of space, their language, crew relationships, culture, and desire to succeed.

"I saw reflections of our own journey to Mars," he says.

But if there was one inaccuracy, Lindgren says it would have to be the space walks, which were more dramatic in the movie. "We would not be that cavalier about space walks," he explains. "But there's reality and then there's the excitement of the movie, and we understand that of course."

The most memorable moment in space was seeing the Northern Lights.

Lindgren says there are "so many" moments that will stay with him forever, such as the launch date, arriving at the ISS, seeing the Earth for the first time from space, and his first space walk.

But he says the only moment that gave him goosebumps was looking down at the Earth as they flew over the Aurora Borealis (also known as Northern Lights) that covered his entire field of view.

"These undulating bright bands of neon green and purple and red sweeping the Earth below us was just indescribable," he says.

He says the most surprising thing about being in space is that it becomes mundane.

"The novelty of floating faded so quickly," Lindgren says. "I describe it as one of my greatest disappointments of flying in space."

He says that his brain had adjusted to floating within the first three to four days that he was there — even though he would still sometimes accidentally knock stuff off the walls and kick his colleagues' crew quarter doors open at times. "I got better at it, and it was still amazingly fun to float around, but I was disappointed that my brain had accepted that it was normal."

He says it's a testament to how quickly our brains adapt to new situations.

After returning from a mission, you're given two months to recuperate and debrief.

When Lindgren returned to Earth in early December 2015, he immediately started a month of medical testing, reconditioning, and research data collection.

The second month back was dedicated to debriefing. He met with all the different teams that supported his training and space flight to discuss what went well and what could have be done better in the future.

The third, fourth, fifth, and sixth months back (he's currently in his fourth month) are dedicated to post-flight appearances. Lindgren says he's mainly focusing on talking to schools and organizations that were a part of his journey.

When the press period ends in mid-June 2016, Lindgren will take a two-week vacation with his family and then start working at a technical job in the astronaut office to support those currently in space and those preparing for space. And if he's lucky, he says, he'll get to go back some day.

"I hope I get to fly again. I'll essentially be getting in the back of the line and hoping there's an opportunity for me to fly again sometime in the future."

He has two pieces of advice for aspiring astronauts.

Lindgren's first piece of advice is to make education and career decisions based on what you want to do, not what you think NASA wants in their astronauts.

"If you do things in your life to become an astronaut and don't end up getting accepted, then you've led a life for someone else instead of yourself," he explains.

For example, Lindgren was a parachuter in the Air Force, which he loved, and then became a doctor — a practice he said he would have been happy doing the rest of his life if NASA had not accepted him.

His second piece of advice is to focus on being the best at whatever you're doing in that moment.

"Ultimately NASA is looking for the best people in their respective fields so if you spend all of your time dreaming and not working hard at what you're doing at the moment, you're not going to be as successful as you could be," he says.

So while it's okay to set goals to work toward, Lindgren says he had to remind his younger self to concentrate on being the best medical student possible and then the best emergency resident possible and so on, and eventually he looked up and had reached his goal to be an astronaut.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement