- Home

- Military & Defense

- Niger is the most amazing country I never expected to visit

Niger is the most amazing country I never expected to visit

The country gets its name from the Niger River, which flows past Niamey, the capital ...

... but the Niger only flows for a few hundred miles in Niger, along the country's southwestern edge. The rest of it is dry savannah ...

... or desert that's as sandy, flat, and desolate as the ocean floor.

One of the country's major highways links Niamey, the capital, with Agadez, a 500-year-old trading city at the Sahara Desert's doorstep. Although Niger is dry and landlocked, there's enough water to support large cattle herds — which will cross the highway whenever they feel like it.

The road between Niamey and Agadez also goes to Arlit, the center of Niger's uranium industry. The so-called uranium highway has crumbled under decades of heavy traffic, and in many places it's safer to just drive around the road. Here, a passenger bus streaks down a dirt track parallel to the highway.

The Tuareg are one of the most important ethnic communities in northern Niger. They're desert traders and herders, and have long been romanticized as fierce Saharan warriors almost preternaturally attuned to the rigors of life in one of the most intense environments on earth. At this encampment of Tuareg herders three hours from Agadez, people gather in the shade of the area's few trees.

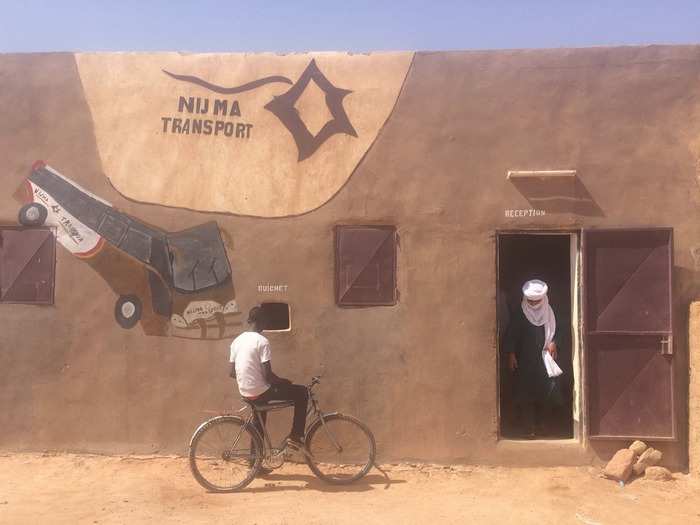

Agadez has been a desert hub for centuries. Today, everything from gold to migrants — to US surveillance drones, reportedly — passes through the city.

The mud minaret of the Great Mosque of Agadez has hovered over the city for nearly 500 years.

It's an architectural wonder — a desert skyscraper that reflects its austere surroundings, but has an almost otherworldly power that sets it apart.

Here's what the mosque's inner courtyard looks like.

Visitors can climb on the roof and see the minaret up close.

Another look at the minaret from the mosque's roof.

From the side, it's possible to get an idea of the minaret's meticulous geometry — the tapering pyramidal design and gridded wooden supporters that have kept it looming over the city and calling the faithful to prayer for five centuries.

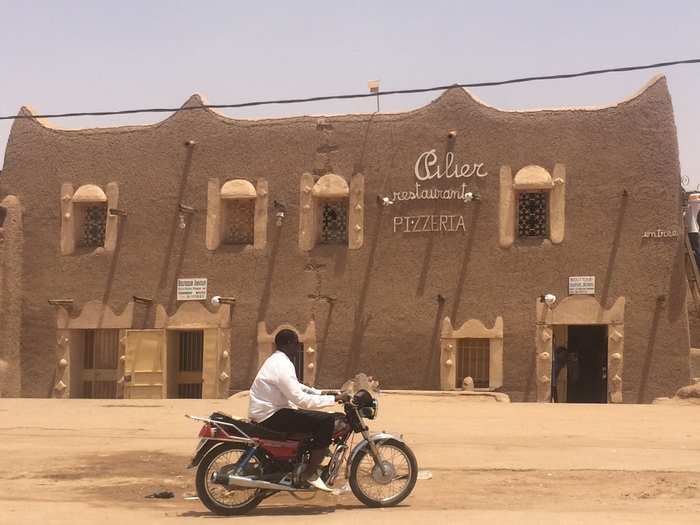

Agadez is hot, dusty, and feels like it's a long way from the rest of the world. It's almost miraculous that it's home to one of the best Italian restaurants in West Africa.

The Pilier is in a sprawling mud-brick building. It used to do brisk business with tourists who visited Agadez and used the city as a base for exploring the nearby desert wilderness. Security concerns have just about ended tourism, but the Pilier still gets aid workers, UN staffers, traders, consultants, and security personnel eating in its courtyard.

The food is amazing. I had ricotta and spinach ravioli, garnished with thick Parmesan cheese. The Pilier makes its own pasta, and brings a lot of its ingredients from Niamey in refrigerated trucks, from some 600 miles away.

In northern Niger, the Pilier can be a much-needed break from the local, often lamb-heavy diet. It definitely makes the best pizza in town.

Getting around is tough in Niger — when we made it to Arlit, pictured here, it was dizzying to think that we were more than a 24-hour drive from Niamey, down roads that are in a dangerous state of disrepair, and that pass through shadeless and uninhabited stretches of desert.

In northern Niger, a lot of people get around this way: by piling into the back of a pickup truck and setting out down an improvised dirt track.

In some places, people still use camels to get between cities.

The Sahara really starts to get serious somewhere between Agadez and Arlit, which are about five hours apart by road.

In Arlit, you definitely feel like you're in a desert. Here, a soccer game continues outside the Cominak uranium mine's worker village, despite a sudden dust storm.

Every country has its roadside landmarks, and Niger is no different. Outside of Tahoua, about halfway between Arlit and Niamey, an arch shaped like two camels wishes travelers a happy journey.

It's amazing to watch the topography, the environment, and even the economy and society change during the long drive between north and south. The north is herder country, but at some point you start seeing radish-domed grain silos and pale-green millet fields. The Tuareg desert gives way to the Hausa watershed, and the loneliness of the northern roads is replaced with the buzz of heavy trucks heading towards the Nigerian border.

The silos are one of the country's iconic sights — little mountain ranges of huddled domes bursting out low-slung villages. Some towns have dozens of them.

Larger villages have mosques with brilliant mud-carved facades.

Niger has a population of around 19 million, and is projected to have over 50 million people by 2050. But it's a very large country, and, from the air, a lot of it looks pretty empty.

There's some fun stuff to do in Niamey — at the Grand Hotel, you can have a drink at sunset while watching the river below ...

... but the best thing to do is to go out on the river itself and look for hippos.

I got in this motorized wooden boat early on a Saturday morning in search of some of the most dangerous — yet most delightful! — animals on earth.

We saw them about an hour upstream from Niamey. Their snouts poke out of the water, and their blowholes give off little clouds of mist.

Hippos are huge. In the wild, it feels like even the small ones are the size of a car.

They're safe to look at from a distance — but as my guide explained, they'll start charging if they feel their kids are threatened. And they're faster than they look.

Hippos spend a lot of their time under water, with only their eyes and noses above the surface. But they have to come up for air every once in awhile.

Niamey is also an hour from the last wild giraffe herd in West Africa. For whatever reason, this parched, flat plane in a place called Koure is home to the last 400 wild giraffes within hundreds of miles.

It doesn't take long to find them — they're taller than everything else around.

The giraffes are almost like living skyscrapers. Like the hippos, they feel like giants from another world.

The giraffes browse the trees, and even gallop at times.

Entire families are out munching on leaves and grass.

The herd has grown over the past few decades — 20 years ago, there were only 50 giraffes left in Koure. Now there are over 400.

Niamey can be a chaotic city. But major roads are being paved, infrastructure is being upgraded, and it feels like a pretty safe place, so long as someone else is driving.

Niger's national museum is in a collection of architecturally distinct buildings, designed based on traditional architectural styles.

The museum's main attraction is the legendary Tree of Tenere. The tree grew in the middle of the Tenere region of the Sahara, and was the only tree for hundreds of miles around — enough of a landmark for it to be depicted on maps. This symbol of nature's persistence fell victim to a perennial human weakness: In 1973, a drunk truck driver struck the tree, killing it. Its trunk and branches have been at the museum ever since.

Another view of the museum.

The food in Niamey is excellent, thanks to the city's mix of people from all over West Africa and the broader French-speaking world — great French and Lebanese food is easy to come by, for instance. If you want to try something new, grab some friends and split a traditional Senegalese platter, with cabbage, fish, onions, and some very spicy peppers.

I spent my last few West African Francs at Niamey's Artisanal Village, where everything from Fulani hats to the Tuareg leatherwork is on offer.

Even if you never make it to Niger, the country's a reminder that there are interesting and unexpected things everywhere — and that any country, no matter how obscure it may seem, can be its own adventure.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement