- Home

- Military & Defense

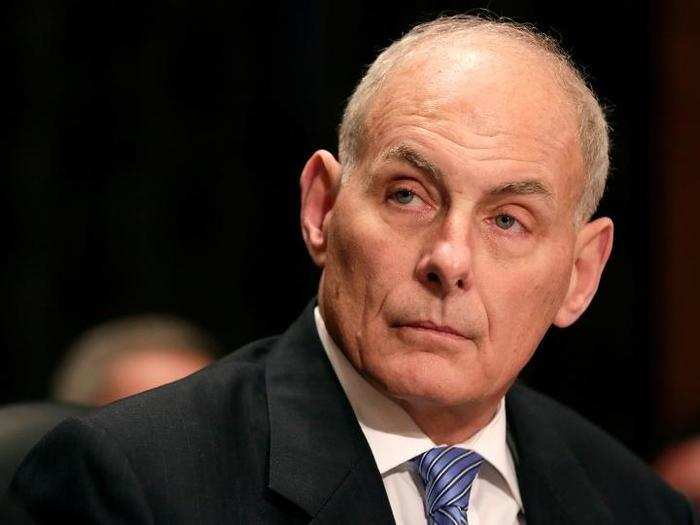

- How John Kelly, America's longest-serving general, worked his way up from the Marines into the White House

How John Kelly, America's longest-serving general, worked his way up from the Marines into the White House

Kelly has had a noticeable effect on the West Wing so far, but skeptics are unsure the newfound discipline will last.

And Kelly was reluctant to take up the chief of staff position, having reportedly been asked by Trump several times to step into the role.

Trump initially offered the job to Kelly in mid-May, according to The Washington Post. Kelly responded that he was flattered but had more to accomplish at the DHS.

"The president has tried to convince the general multiple times, and the general has politely declined several times," one administration official told the Post. "But given what's going on in Washington, I think the president really needs the general to help him restore order in this White House and advance his vision."

Kelly finally agreed to take up the role after Trump asked for former chief of staff Reince Priebus' resignation.

Working in the Trump administration hasn't all been smooth sailing for Kelly — he reportedly considered resigning after Trump abruptly fired FBI director James Comey in May.

Kelly told Comey in a phone call that he was considering stepping down in a show of defiance at the president's actions, one former law enforcement official familiar with the conversation told The New York Times.

He was criticized for joking to Trump that he should use a ceremonial sword he had just been given "on the press."

Though the remark was clearly intended as a joke, Kelly received some backlash from those who have criticized the Trump administration for being particularly hostile to the media.

Gen. Kelly tells Pres. Trump "you can use that on the press" after he's presented with ceremonial saber at Coast Guard Academy commencement. pic.twitter.com/xj73oHxUdZ

— ABC News (@ABC) May 17, 2017

Yet Kelly has also fallen short of some of those expectations, taking up a hardline stance on issues such as deportations and border security that align closely with Trump's views.

Kelly raised more than a few eyebrows last April when he gave a fiery speech shutting down lawmakers who had criticized the Department of Homeland Security for enforcing Trump's travel ban and ramping up deportations.

"If lawmakers do not like the laws they've passed and we are charged to enforce, then they should have the courage and skill to change the laws," Kelly said. "Otherwise they should shut up and support the men and women on the front lines."

Democratic lawmakers in particular were appalled by Kelly's tone.

"This is not boot camp," Democratic Rep. Joseph Crowley of New York told The Washington Post after a combative meeting with Kelly. "This is not newly inducted members of the Marine Corps. These are experienced lawmakers who understand the law."

Kelly's appointment as Homeland Security secretary was reassuring to many Trump critics, who viewed him as a qualified, level-headed pick amid an otherwise inexperienced and controversial cabinet.

Kelly, Secretary of Defense James Mattis, and national security adviser H.R. McMaster together make up what has been nicknamed the "axis of adults" within the Trump administration.

They have had a calming effect on those who feared that Trump's temperament and impulsivity would lead to rash decisions, particularly in the foreign policy arena.

He retired from the military in January 2016, after more than 45 years of service.

Speaking on his legacy in the Marines, Kelly said, "One day, you'll get out of the Marine Corps, you'll put your uniform up, but you'll never not be a marine."

Kelly helped facilitate a controversial exchange of five Taliban commanders detained in Guantanamo Bay for the captured US Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl in 2014.

The Obama administration’s decision to trade five Taliban detainees for Bergdahl, the US soldier who walked away from his base in Afghanistan and spent five years in captivity, was a controversial one. Kelly later told reporters that he knew the prisoner exchange "caused a lot of angst in a lot of areas," but said his job was not to slow down transfers — it was to facilitate them.

He even ensured that the press that had gathered at Guantanamo Bay didn’t see the prisoners leave the site.

"It was a dicey transfer because we had an awful lot of the press down there ... In fact, when the press were waiting for their airplane and the families of the 9/11 crowd and all of us were don there, we were doing the transfer and we never got caught," he said.

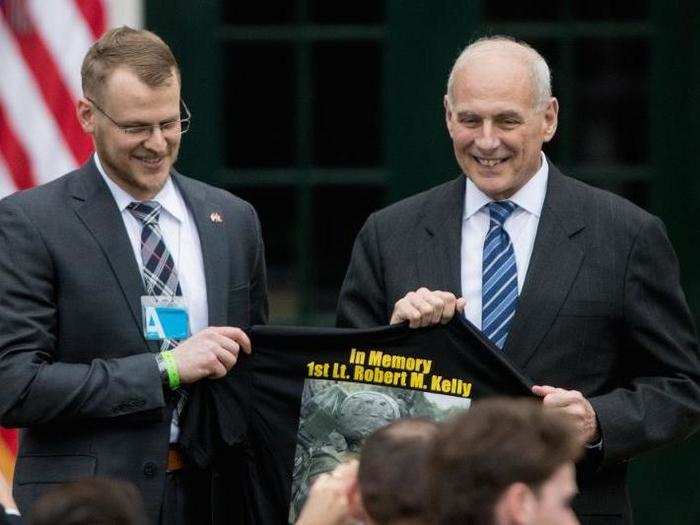

Kelly's son, 1st Lt. Robert Kelly, was killed in action in 2010.

The 29-year-old was killed when he stepped on a land mine in Afghanistan, where he was leading a platoon of Marines. His death made the senior Kelly the highest-ranking military officer to lose a child in Iraq or Afghanistan, according to The New York Times.

He once lamented that being promoted as an officer took him "further and further away from day-to-day contact with young Marines."

"My whole last tour in Iraq, I was always on the road," Kelly said. "To show up to a [forward operating base] in the middle of nowhere or at a convoy that's broken down and talk to [Marines] as they're changing the tire is the only way to do business."

Kelly rose quickly within the ranks of the Marines, and served during the Persian Gulf War — including Operation Desert Storm — and the Iraq war.

Kelly served in numerous positions throughout the Marine Corps, even once serving as the Commandant's Liaison Officer to the US House of Representatives — an introduction to lawmakers and the political process.

"He knows how Congress works," Carl Fulford, a retired four-star Marine Corps general told USA Today.

John Kelly is a Boston native who enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1970.

"In the America I grew up in, every male was a veteran; my dad, my uncles and all the people on the block," Kelly said in an interview posted on the Marines' website. "So, with that kind of background and the draft, you assumed you were going to go into the service when your time came."

He served as an infantryman with the 2nd Marine Division in Lejeune, North Carolina, but left in 1972 to attend the University of Massachusetts in Boston. He later returned to the 2nd Marine Division after attending the Officer Candidates School, serving as a platoon commander and working his way up to an infantry company commander.

He also received master's degrees from Georgetown and the National Defense University.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement