17 rules for using commas correctly without looking like a fool

Juliana Kaplan

- Commas don't just signify pauses in a sentence — precise rules govern when to use this punctuation mark.

- Commas are needed before coordinating conjunctions, after dependent clauses (when they precede independent clauses), and to set off appositives.

- The Oxford comma reduces ambiguity in lists.

Contrary to popular belief, commas don't just signify pauses in a sentence.

In fact, precise rules govern when to use this punctuation mark. When followed, they lay the groundwork for clear written communication.

We've compiled a list of all the times when you'll need the mighty comma — and we wrote sentences about ducks to show you their proper use:

Rebecca Aydin and Christina Sterbenz contributed to a previous version of this post.

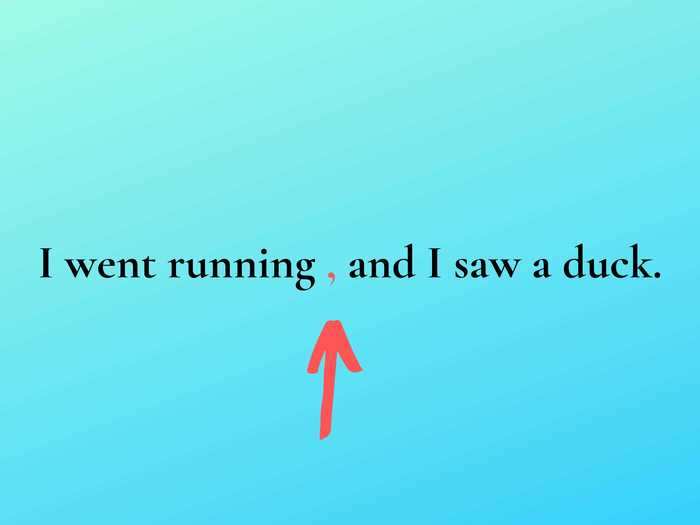

1. Use a comma before any coordinating conjunction (and, but, for, or, nor, so, yet) that links two independent clauses.

You may need to learn a few grammatical terms to understand this one.

An independent clause is a unit of grammatical organization that includes both a subject and verb and can stand on its own as a sentence. In the previous example, "I went running" and "I saw a duck" are both independent clauses, and "and" is the coordinating conjunction that connects them. Consequently, we insert a comma.

If we were to eliminate the second "I" from that example, the second clause would lack a subject, making it not a clause at all. In that case, it would no longer need a comma: "I went running and saw a duck."

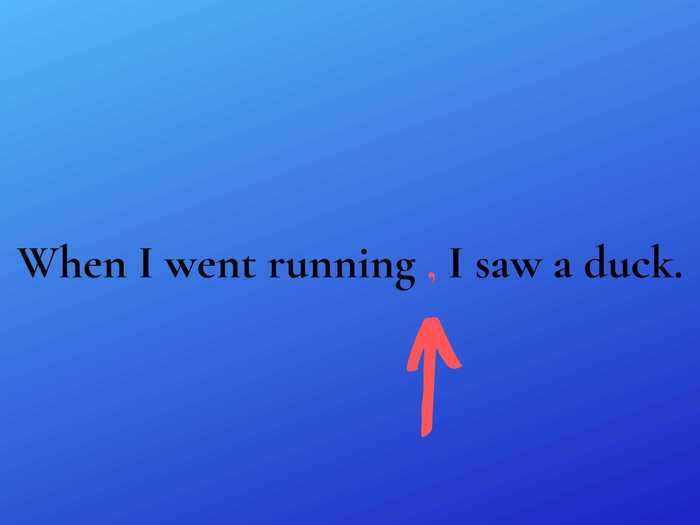

2. Use a comma after a dependent clause that starts a sentence.

A dependent clause is a grammatical unit that contains both subject and verb but cannot stand on its own, like "When I went running ..."

Commas always follow these clauses at the start of a sentence. If a dependent clause ends the sentence, however, it no longer requires a comma. Only use a comma to separate a dependent clause at the end of a sentence for added emphasis, usually when negation occurs.

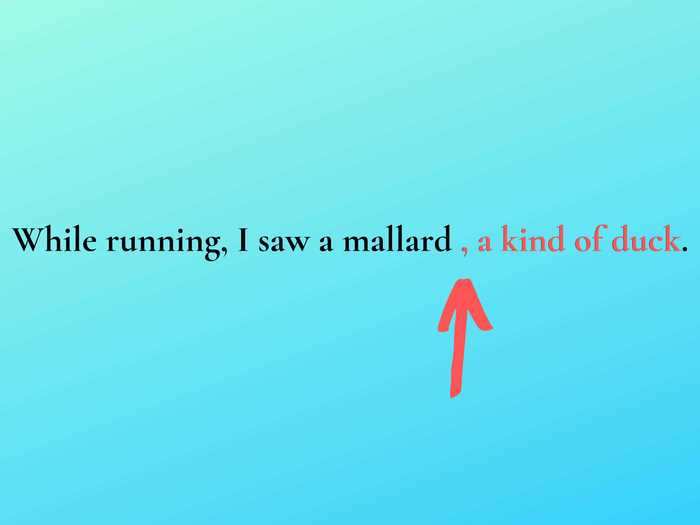

3. Use commas to offset appositives from the rest of the sentence.

Appositives act as synonyms for a juxtaposed word or phrase. In the above example — "While running, I saw a mallard, a kind of duck" — "A kind of duck" is the appositive, which gives more information about "a mallard."

If the appositive occurs in the middle of the sentence, both sides of the phrase need a comma. As in: "A mallard, a kind of duck, attacked me."

Don't let the length of an appositive scare you. As long as the phrase somehow gives more information about its predecessor, you usually need a comma.

"A mallard, the kind of duck I saw when I went running, attacked me."

There's one exception to this rule. Don't offset a phrase that gives necessary information to the sentence. Usually, commas surround a non-essential clause or phrase. For example, "The duck that attacked me scared my friend" doesn't require any commas. Even though the phrase "that attacked me" describes "the duck," it provides essential information to the sentence. Otherwise, no one would know why the duck scared your friend. Clauses that begin with "that" are usually essential to the sentence and do not require commas.

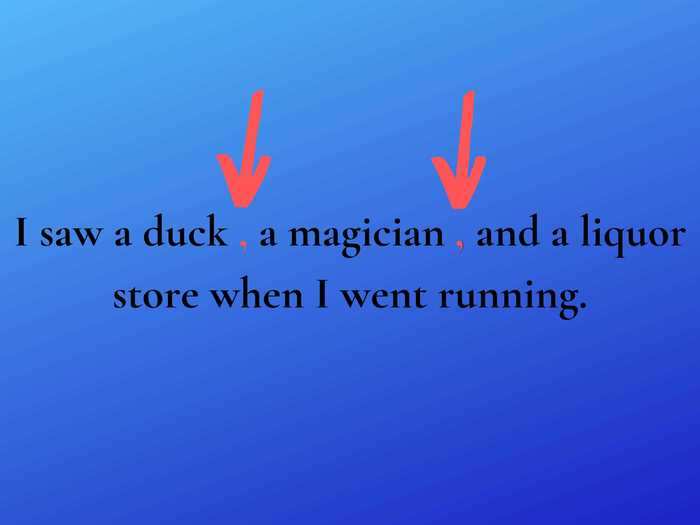

4. Use commas to separate items in a series.

That last comma, known as the serial comma, Oxford comma, or Harvard comma, causes serious controversy. Although many consider it unnecessary, others (including Business Insider) insist on its use to reduce ambiguity.

There's an Internet meme that demonstrates its necessity perfectly. The sentence, "We invited the strippers, JFK, and Stalin," means the speaker sent three separate invitations: one to some strippers, one to JFK, and one to Stalin. The version without the Oxford comma, however, takes on an entirely different meaning, potentially suggesting that only one invitation was sent — to two strippers named JFK and Stalin. Witness: "We invited the strippers, JFK and Stalin."

Read more: 12 everyday phrases that you're probably saying incorrectly

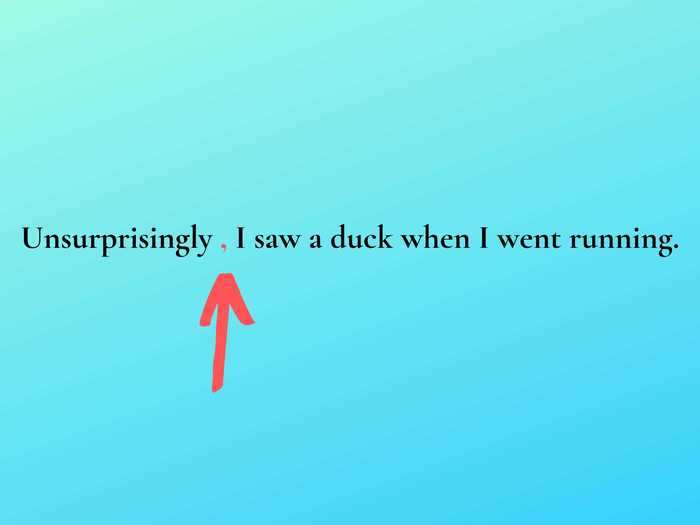

5. Use a comma after introductory adverbs.

Another example: "Finally, I went running."

Many adverbs end in "ly" and answer the question "how?" How did someone do something? How did something happen? Adverbs that don't end in "ly," such as "when" or "while," usually introduce a dependent clause, which rule number two in this post already covered.

Also insert a comma when "however" starts a sentence, too. Phrases like "on the other hand" and "furthermore" also fall into this category.

Starting a sentence with "however," however, is discouraged by many careful writers. A better method would be to use "however" within a sentence after the phrase you want to negate, as in the previous sentence.

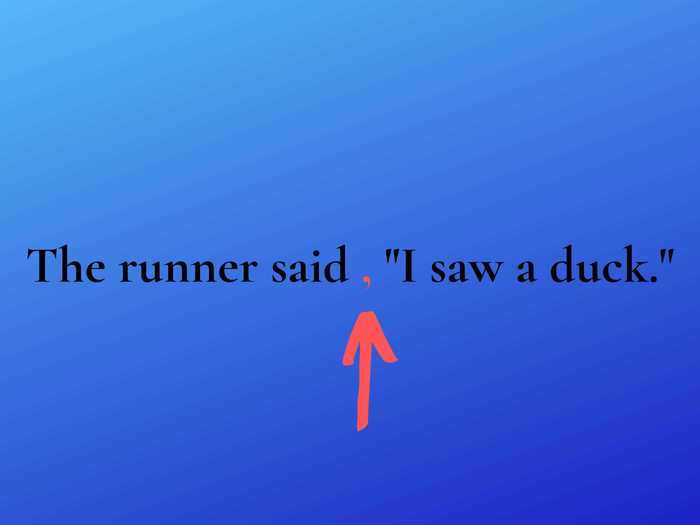

6. Use a comma when attributing quotes.

The rule for where the comma goes, however, depends on where attribution comes.

If attribution comes before the quote, place the comma outside the quotations marks:

The runner said, "I saw a duck."

If attribution comes after the quote, put the comma inside the quotation marks:

"I saw a duck," said the runner.

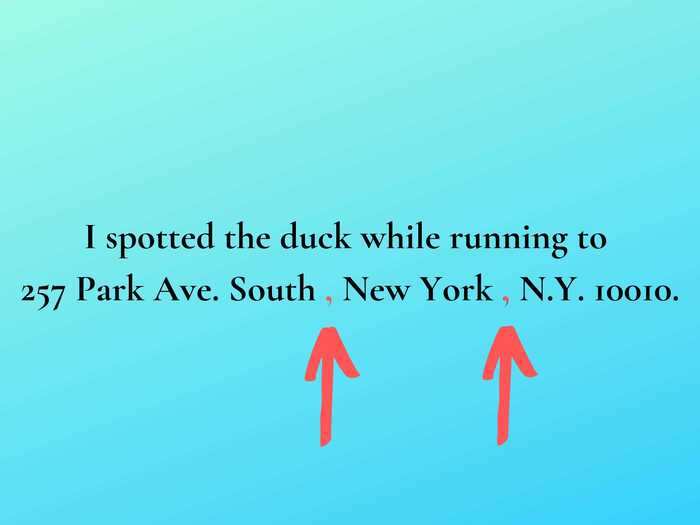

7. Use a comma to separate each element in an address. Also use a comma after a city-state combination within a sentence.

Another example: "Cleveland, Ohio, is a great city."

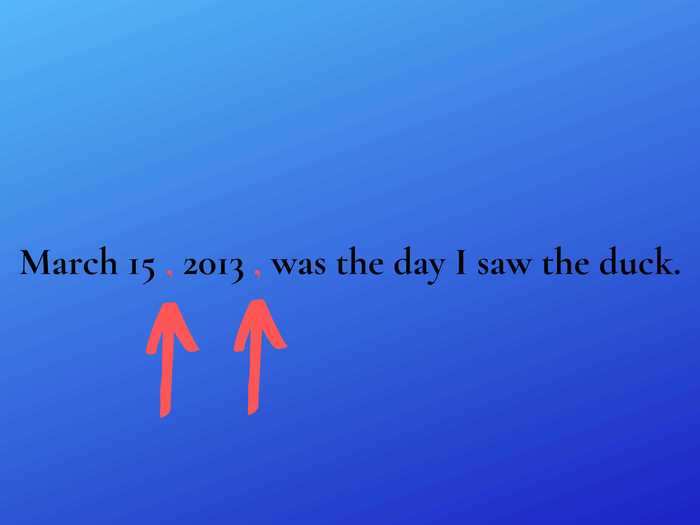

8. Use a comma to separate the elements in a full date (weekday, month and day, and year). Also separate a combination of those elements from the rest of the sentence with commas.

Even if you add a weekday, keep the comma after "2013":

Friday, March 15, 2013, was the day I saw the duck.

Friday, March 15, was the day I say the duck.

You don't need to add a comma when the sentence mentions only the month and year:

March 2013 was a strange month.

Read more: 11 reasons the English language is impossible to learn

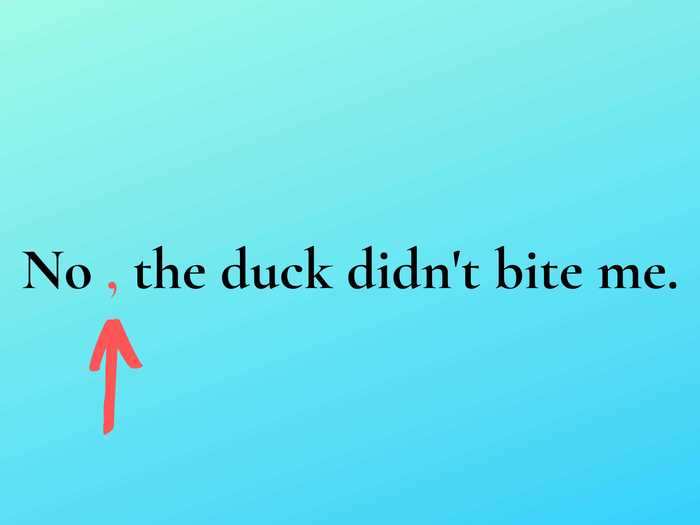

9. Use a comma when the first word of the sentence is a freestanding "yes" or "no."

Another example: "Yes, I saw a duck when I went running."

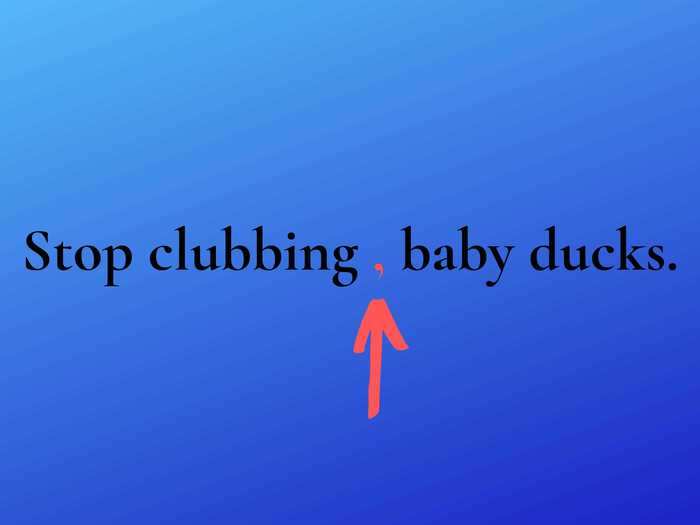

10. Use a comma when directly addressing someone or something in a sentence.

Another clever meme shows the problem with incorrect placement of this comma. "Stop clubbing baby seals" reads like an order to desist harming infant mammals of the seal variety. The version with a comma, however, instructs them to stop attending hip dance clubs. "Stop clubbing, baby seals." (Or rather, to stay on theme: "Stop clubbing, baby ducks.")

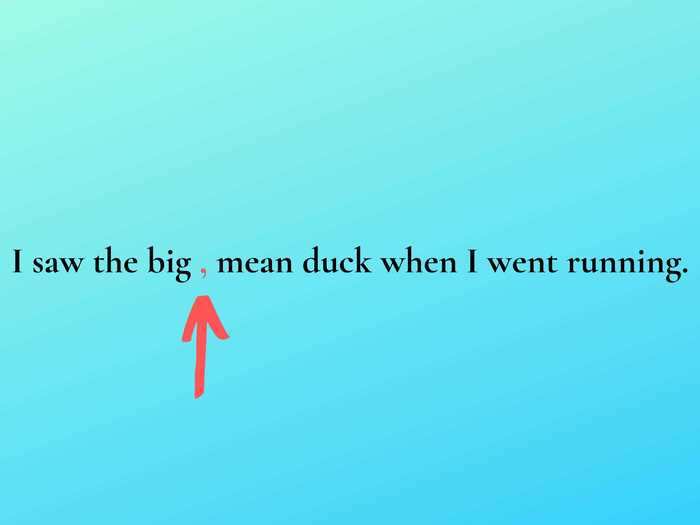

11. Use a comma between two adjectives that modify the same noun.

Only coordinate adjectives require a comma between them. Two adjectives are coordinate if you can answer yes to both of these questions: 1. Does the sentence still make sense if you reverse the order of the words? 2. Does the sentence still make sense if you insert "and" between the words?

Since "I saw the mean, big duck " and "I saw the big and mean duck" both sound fine, you need the comma.

Sentences with non-coordinate adjectives, however, don't require a comma. For example, "I lay under the powerful summer sun." "Powerful" describes "summer sun" as a whole phrase. This often occurs with adjunct nouns, a phrase where a noun acts as an adjective describing another noun — like "chicken soup" or "dance club."

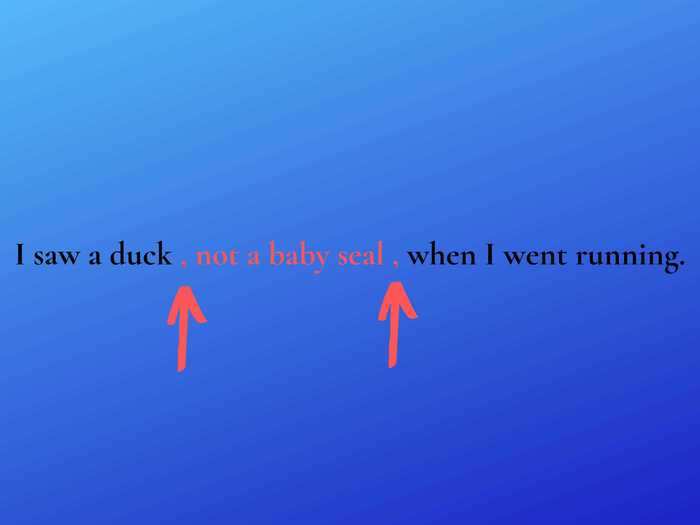

12. Use a comma to offset negation in a sentence.

In this case, you still need the comma if the negation occurs at the end of the sentence:

"I saw a baby seal, not a duck."

Also use commas when any distinct shift occurs in the sentence or thought process:

"The cloud looked like an animal, perhaps a baby seal."

Read more: 9 ways to become a better speller, according to an expert

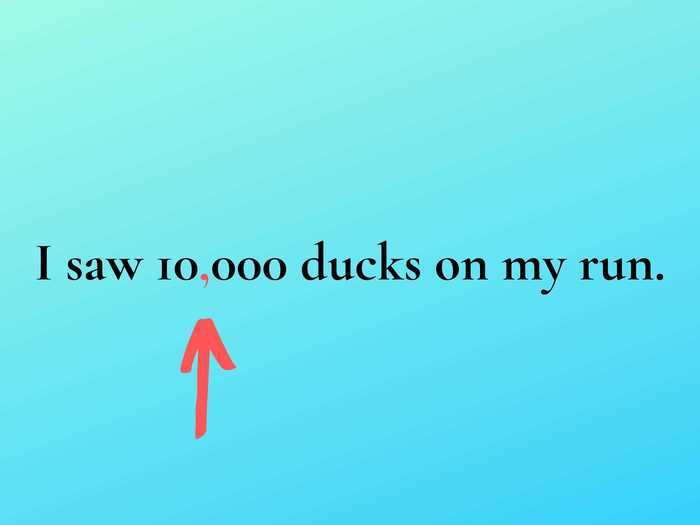

13. Use commas before every sequence of three numbers when writing a number larger than 999. (Two exceptions are writing years and house numbers.)

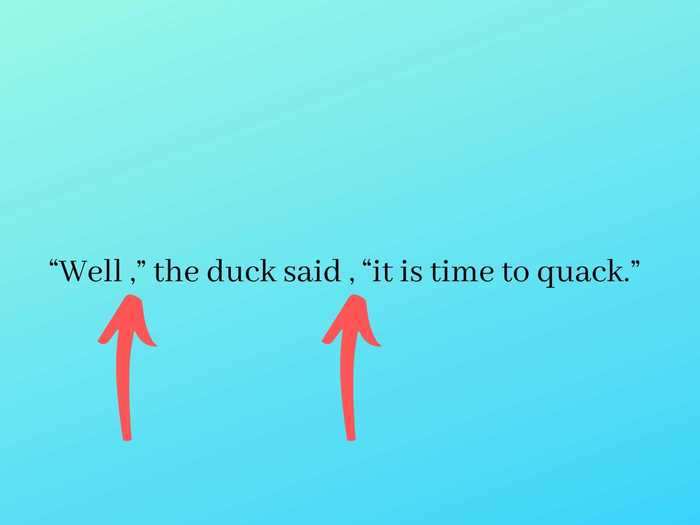

14. Use commas to demarcate an incomplete quote, or to create dramatic effect.

If you're trying to indicate a natural pause or inject your dialogue with some dramatic effect, commas can be your friend. Put whatever comes first in quotes, end that quote with a comma, and then end the attribution with a comma. This creates the grammatical equivalent of someone pausing while speaking — the commas make you stop at each clause, but let you know that the sentence is still flowing.

"But wait," the Business Insider reporter wrote, "there's more ways to use commas."

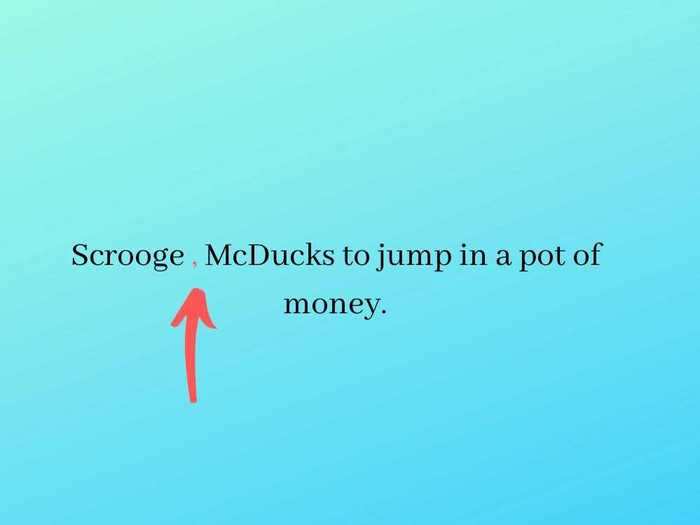

15. Use commas for important clarification.

In the above sentence, a comma tells you that Scrooge and the extended McDuck clan are to jump in a pot of money. Without the comma, it would seem that multiple Scrooges were raking in the coins.

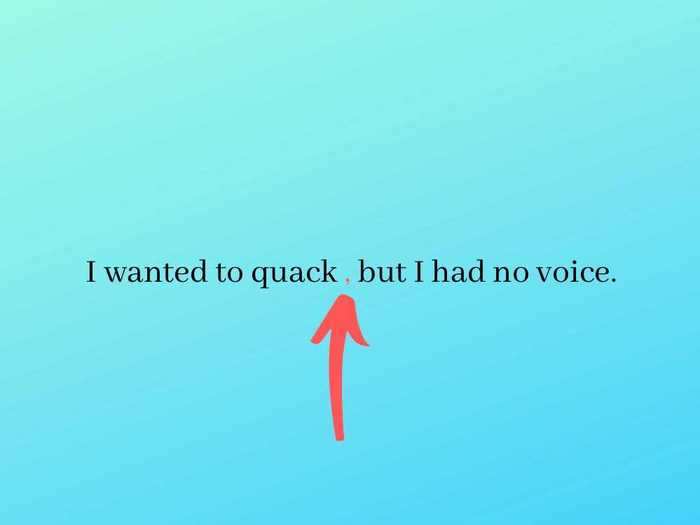

16. Beware of putting a comma before "but" every single time. It should only be used when connecting two independent clauses (despite what your middle school teacher told you).

As you may recall from above, an independent clause has a subject and a verb and can stand on its own as a sentence. Often, a coordinating conjunction will connect two independent clauses — like the word "but."

But — and it's a big but — your middle school teacher may have told you to always throw a comma before "but." Don't do that! You should only put a comma before "but" when connecting two independent clauses.

For example, this usage of "but" does not take a comma:

"To quack but to have no one hear is a sad thing for a duck."

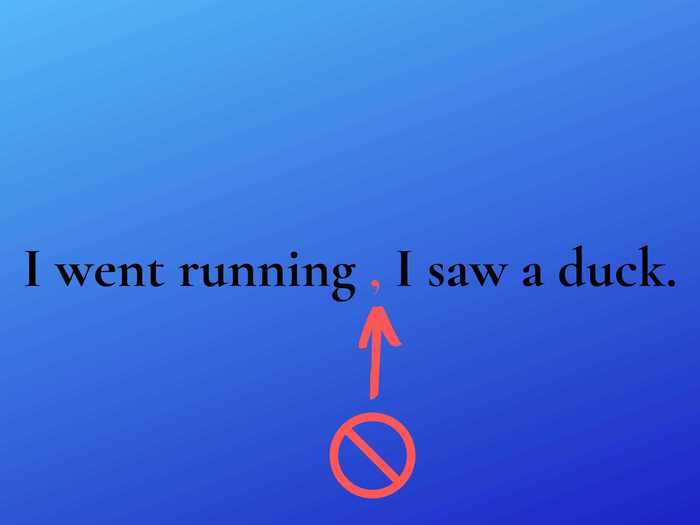

17. Beware of the comma splice

As fun as it may be to say, the comma "splice" should be avoided. A comma splice incorrectly joins two independent clauses, like:

"I went running, I saw a duck."

That sentence contains a comma splice, and therefore it is incorrect. The two independent clauses "I went running" and "I saw a duck" could instead be separated by a period.

Read more: 9 words and phrases people think are wrong, but are actually correct

READ MORE ARTICLES ON

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement