58 cognitive biases that screw up everything we do

Affect heuristic

Anchoring bias

People are overreliant on the first piece of information they hear.

In a salary negotiation, for instance, whoever makes the first offer establishes a range of reasonable possibilities in each person's mind. Any counteroffer will naturally react to or be anchored by that opening offer.

"Most people come with the very strong belief they should never make an opening offer," said Leigh Thompson, a professor at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management. "Our research and lots of corroborating research shows that's completely backwards. The guy or gal who makes a first offer is better off."

Confirmation bias

We tend to listen only to the information that confirms our preconceptions. Once you've formed an initial opinion about someone, it's hard to change your mind.

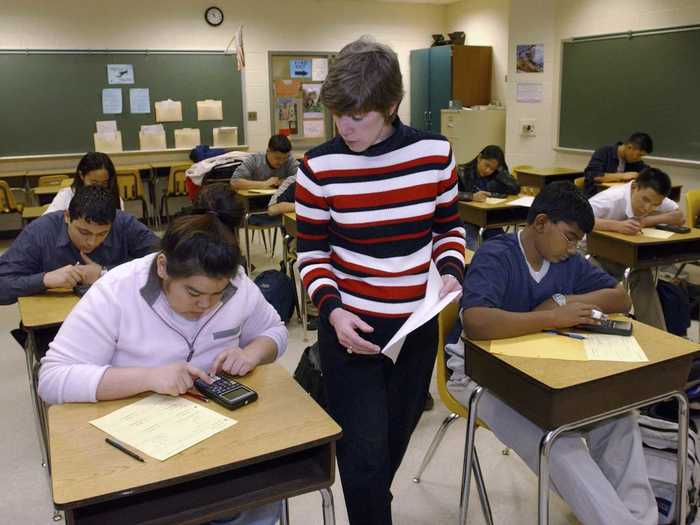

For example, researchers had participants watch a video of a student taking an academic test. Some participants were told that the student came from a high socioeconomic background; others were told the student came from a low socioeconomic background. Those in the first condition believed the student's performance was above grade level, while those in the second condition believed the student's performance was below.

If you know some information about a job candidate's background, you might be inclined to use that information to make false judgments about his or her ability.

Observer-expectancy effect

A cousin of confirmation bias, here our expectations unconsciously influence how we perceive an outcome. Researchers looking for a certain result in an experiment, for example, may inadvertently manipulate or interpret the results to reveal their expectations.

That's why the "double-blind" experimental design was created for the field of scientific research.

Bandwagon effect

The probability of one person adopting a belief increases based on the number of people who hold that belief. This is a powerful form of groupthink — and it's a reason meetings are often so unproductive.

Bias blind spots

Failing to recognize your cognitive biases is a bias in itself.

Notably, Princeton psychologist Emily Pronin has found that "individuals see the existence and operation of cognitive and motivational biases much more in others than in themselves."

Choice-supportive bias

When you choose something, you tend to feel positive about it, even if the choice has flaws. You think that your dog is awesome — even if it bites people every once in a while — and that other dogs are stupid, since they're not yours.

Clustering illusion

This is the tendency to see patterns in random events. It is central to various gambling fallacies, like the idea that red is more or less likely to turn up on a roulette table after a string of reds.

Conservatism bias

Where people believe prior evidence more than new evidence or information that has emerged. People were slow to accept the fact that the Earth was round because they maintained their earlier understanding the planet was flat.

Conformity

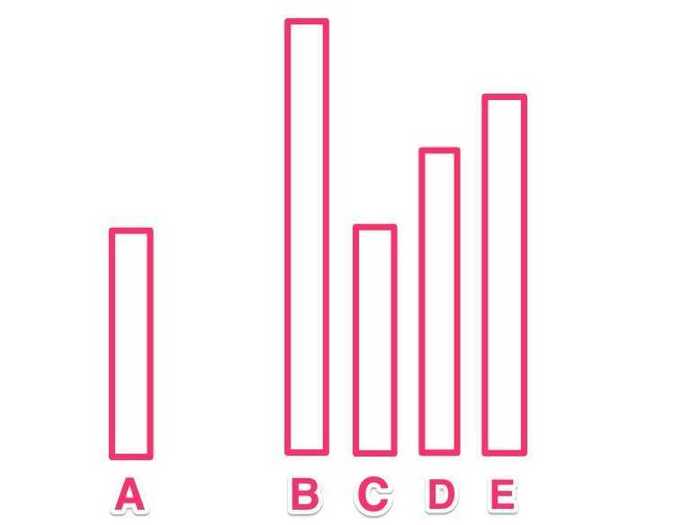

This is the tendency of people to conform with other people. It is so powerful that it may lead people to do ridiculous things, as shown by the following experiment by Solomon Asch.

Ask one subject and several fake subjects (who are really working with the experimenter) which of lines B, C, D, and E is the same length as A? If all of the fake subjects say that D is the same length as A, the real subject will agree with this objectively false answer a shocking three-quarters of the time

"That we have found the tendency to conformity in our society so strong that reasonably intelligent and well-meaning young people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern,"Asch wrote. "It raises questions about our ways of education and about the values that guide our conduct."

Curse of knowledge

When people who are more well-informed cannot understand the common man. For instance, in the TV show "The Big Bang Theory," it's difficult for scientist Sheldon Cooper to understand his waitress neighbor Penny.

Decoy effect

A phenomenon in marketing where consumers have a specific change in preference between two choices after being presented with a third choice.

In his TED Talk, behavioral economist Dan Ariely explains the "decoy effect" using an old Economist advertisement as an example.

The ad featured three subscription levels: $59 for online only, $159 for print only, and $159 for online and print. Ariely figured out that the option to pay $159 for print only exists so that it makes the option to pay $159 for online and print look more enticing than it would if it was just paired with the $59 option.

Denomination effect

People are less likely to spend large bills than their equivalent value in small bills or coins.

Duration neglect

When the duration of an event doesn't factor enough into the way we consider it. For instance, we remember momentary pain just as strongly as long-term pain.

Kahneman and colleagues tracked patients' pain during colonoscopies (they used to be more uncomfortable) and found that the end of the procedure pretty much determined patients' evaluations of the entire experience. One set of patients underwent a shorter procedure in which the end was relatively painful. The other set of patients underwent a longer procedure in which the end was less painful.

Results showed that the second set of patients (the longer colonoscopy) rated the procedure as less painful overall.

Availability heuristic

When people overestimate the importance of information that is easy to remember.

In one experiment, a professor asked students to list either two or 10 ways to improve his class. Students that had to come up with 10 ways gave the class much higher ratings, likely because they had a harder time thinking about what was wrong with the class.

This phenomenon could easily apply in the case of job interviews. If you have a hard time recalling what a candidate did wrong during an interview, you'll likely rate him higher than if you can recall those things easily.

Empathy gap

Where people in one state of mind fail to understand people in another state of mind. If you are happy, you can't imagine why people would be unhappy. When you are not sexually aroused, you can't understand how you act when you are sexually aroused.

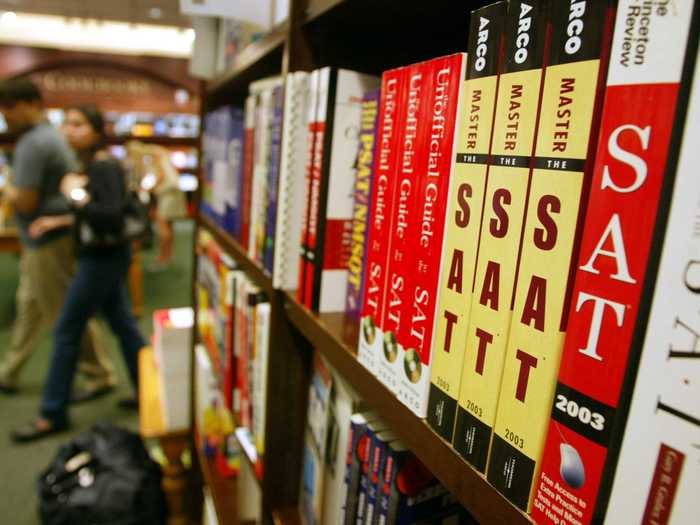

Frequency illusion

Where a word, name or thing you just learned about suddenly appears everywhere. Now that you know what that SAT word means, you see it in so many places!

Fundamental attribution error

This is where you attribute a person's behavior to an intrinsic quality of her identity rather than the situation she's in. For instance, you might think your colleague is an angry person, when she is really just upset because she stubbed her toe.

Galatea effect

Where people succeed — or underperform — because they think they should.

Call it a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, in schools it describes how students who are expected to succeed tend to excel and students who are expected to fail tend to do poorly.

Halo effect

Where we take one positive attribute of someone and associate it with everything else about that person or thing.

It helps explain why we often assume highly attractive individuals are also good people, why they tend to get hired more easily, and why they earn more money.

Hard-easy bias

Where everyone is overconfident on easy problems and not confident enough for hard problems.

Hindsight bias

Of course Apple and Google would become the two most important companies in phones — but tell that to Nokia, circa 2003.

One classic experiment on hindsight bias took place in the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon was about to depart for trips to China and the Soviet Union. Researchers asked the participants to predict various outcomes. After the trips, researchers asked participants to recall the probabilities that had intially assigned to each outcome.

Results showed that participants remembered having rated the events unlikely if the event had not occurred, and remembered having rated the events likely if the event had occurred.

Hyperbolic discounting

The tendency for people to want an immediate payoff rather than a larger gain later on.

Ideometer effect

Where an idea causes you to have an unconscious physical reaction, like a sad thought that makes your eyes tear up. This is also how Ouija boards seem to have minds of their own.

Illusion of control

The tendency for people to overestimate their ability to control events, like when a sports fan thinks his thoughts or actions had an effect on the game.

Information bias

The tendency to seek information when it does not affect action. More information is not always better. Indeed, with less information, people can often make more accurate predictions.

In one study, people who knew the names of basketball teams as well as their performance records made less accurate predictions about the outcome of NBA games than people who only knew the teams' performance records. However, most people believed that knowing the team names was helpful in making their predictions.

Inter-group bias

We view people in our group differently from how see we someone in another group. This bias helps illuminate the origins of prejudice and discrimination.

Unfortunately, researchers say we aren't always aware of our preference for people in our social group.

Irrational escalation

When people make irrational decisions based on past rational decisions. It may happen in an auction, when a bidding war spurs two bidders to offer more than they would other be willing to pay.

Negativity bias

The tendency to put more emphasis on negative experiences rather than positive ones. People with this bias feel that "bad is stronger than good" and will perceive threats more than opportunities in a given situation.

Psychologists argue it's an evolutionary adaptation — it's better to mistake a rock for a bear than a bear for a rock.

In modern times, the negativity bias has meaningful implications for our relationships. John Gottman, a relationship expert, found that a stable relationship requires that good experiences occur at least five times more often than bad experiences.

Omission bias

The tendency to prefer inaction to action, in ourselves and even in politics.

Psychologist Art Markman gave a great example back in 2010:

The omission bias creeps into our judgment calls on domestic arguments, work mishaps, and even national policy discussions. In March, President Obama pushed Congress to enact sweeping health care reforms. Republicans hope that voters will blame Democrats for any problems that arise after the law is enacted. But since there were problems with health care already, can they really expect that future outcomes will be blamed on Democrats, who passed new laws, rather than Republicans, who opposed them? Yes, they can—the omission bias is on their side.

Ostrich effect

The decision to ignore dangerous or negative information by "burying" one's head in the sand, like an ostrich. Research suggests that investors check the value of their holdings significantly less often during bad markets.

But there's an upside to acting like a big bird, at least for investors. When you have limited knowledge about your holdings, you're less likely to trade, which generally translates to higher returns in the long run.

Outcome bias

Judging a decision based on the outcome — rather than how exactly the decision was made in the moment. Just because you won a lot in Vegas doesn't mean gambling your money was a smart decision.

Research illustrates the power of the outcome bias on the way we evaluate decisions.

In one study, students were asked whether a particular city should have paid for a full-time bridge monitor to protect against debris getting caught and blocking the flow of water. Some students only saw the information that was available at the time of the city's decision; others saw the information that was available after the decision was already made: debris had blocked the river and caused flood damage.

As it turns out, 24% of students in the first group (with limited information) said the city should have paid for the bridge, compared to 56% of students in the second group (with all information). Hindsight had affected their judgment.

Overconfidence

Some of us are too confident about our abilities, and this causes us to take greater risks in our daily lives.

Perhaps surprisingly, experts are more prone to this bias than laypeople. An expert might make the same inaccurate prediction as someone unfamiliar with the topic — but the expert will probably be convinced that he's right.

Overoptimism

When we believe the world is a better place than it is, we aren't prepared for the danger and violence we may encounter. The inability to accept the full breadth of human nature leaves us vulnerable.

On the flip side, overoptimism may have some benefits — hopefulness tends to improve physical health and reduce stress. In fact, researchers say we're basically hardwired to underestimate the probability of negative events — meaning this bias is especially hard to overcome.

Pessimism bias

This is the opposite of the overoptimism bias. Pessimists over-weigh negative consequences with their own and others' actions.

Those who are depressed are more likely to exhibit the pessimism bias.

Placebo effect

When simply believing that something will have a certain impact on you causes it to have that effect.

This is a basic principle of stock market cycles, as well as a supporting feature of medical treatment in general. People given "fake" pills often experience the same physiological effects as people given the real thing.

Planning fallacy

The tendency to underestimate how much time it will take to complete a task.

According to Kahneman, people generally think they're more capable than they actually are and have greater power to influence the future than they really do. For example, even if you know that writing a project report typically takes your coworkers several hours, you might believe that you can finish it in under an hour because you're especially skilled.

Post-purchase rationalization

Making ourselves believe that a purchase was worth the value after the fact.

Priming

Priming is where if you're introduced to an idea, you'll more readily identify related ideas.

Let's take an experiment as an example, again from Less Wrong:

Suppose you ask subjects to press one button if a string of letters forms a word, and another button if the string does not form a word. (E.g., "banack" vs. "banner".) Then you show them the string "water". Later, they will more quickly identify the string "drink" as a word. This is known as "cognitive priming" ...

Priming also reveals the massive parallelism of spreading activation: if seeing "water" activates the word "drink", it probably also activates "river", or "cup", or "splash."

Pro-innovation bias

When a proponent of an innovation tends to overvalue its usefulness and undervalue its limitations. Sound familiar, Silicon Valley?

Procrastination

Deciding to act in favor of the present moment over investing in the future.

For example, even if your goal is to lose weight, you might still go for a thick slice of cake today and say you'll start your diet tomorrow.

That happens largely because, when you set the weight-loss goal, you don't take into account that there will be many instances when you're confronted with cake and you don't have a plan for managing your future impulses.

Reactance

The desire to do the opposite of what someone wants you to do, in order to prove your freedom of choice.

One study found that when people saw a sign that read, "Do not write on these walls under any circumstances," they were more likely to deface the walls than when they saw a sign that read, "Please don't write on these walls." The study authors say that's partly because the first sign posed a greater perceived threat to people's freedom.

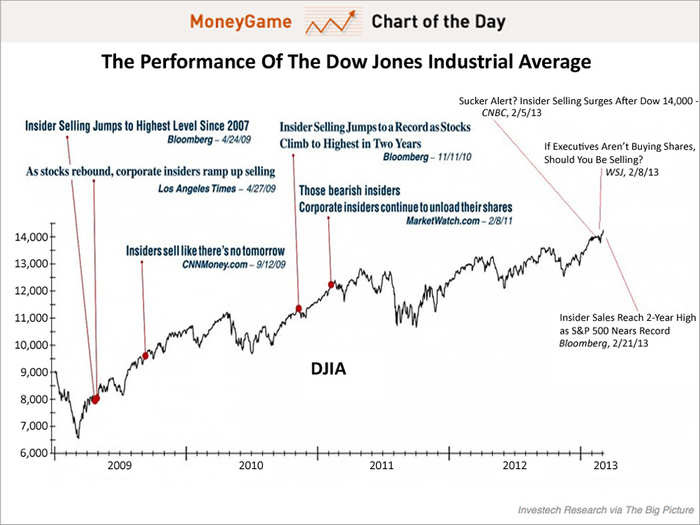

Recency

The tendency to weigh the latest information more heavily than older data.

As financial planner Carl Richards writes in The New York Times, investors often think the market will always look the way it looks today and therefore make unwise decisions: "When the market is down we become convinced that it will never climb out, so we cash out our portfolios and stick the money in a mattress."

Reciprocity

The belief that fairness should trump other values, even when it's not in our economic or other interests.

We learn the reciprocity norm from a young age, and it affects all kinds of interactions. One study found that, when restaurant waiters gave customers extra mints, the customers upped their tips. That's likely because the customers felt obligated to return the favor.

Regression bias

People take action in response to extreme situations. Then when the situations become less extreme, they take credit for causing the change, when a more likely explanation is that the situation was reverting to the mean.

In "Thinking, Fast and Slow," Kahneman gives an example of how the regression bias plays out in real life. An instructor in the Israeli Air Force asserted that when he chided cadets for bad execution, they always did better on their second try. The instructor believed that his reprimands were the cause of the improvement.

Yet Kahneman told him he was really observing regression to the mean, or random variations in the quality of performance. If you perform really badly one time, it's highly probable that you'll do better the next time, even if you do nothing to try to improve.

Salience

Our tendency to focus on the most easily-recognizable features of a person or concept.

For example, research suggests that when there's only one member of a racial minority on a business team, other members use that individual's performance to predict how any member of that racial group would perform.

Scope insensitivity

This is where your willingness to pay for something doesn't correlate with the scale of the outcome.

From Less Wrong:

Once upon a time, three groups of subjects were asked how much they would pay to save 2,000 / 20,000 / 200,000 migrating birds from drowning in uncovered oil ponds. The groups respectively answered $80, $78, and $88. This is scope insensitivity or scope neglect: the number of birds saved — the scope of the altruistic action — had little effect on willingness to pay.

Seersucker illusion

Over-reliance on expert advice. This has to do with the avoidance of responsibility. We call in "experts" to forecast when typically they have no greater chance of predicting an outcome than the rest of the population. In other words, "for every seer there's a sucker."

Selective attention

Allowing our expectations to influence how we perceive the world.

The classic study on selective attention is called the "invisible gorilla" experiment. Psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons created a short film in which a team wearing white and a team wearing black pass basketballs. Participants are asked to count the number of passes made by either the white or the black team. Halfway through the video, a woman wearing a gorilla suit crosses the court, thumps her chest, and walks off screen. She's on screen for a total of nine seconds.

About half of the thousands of people who have watched the video (you can watch it here) don't notice the gorilla, presumably because they're so wrapped up in counting the basketball passes.

Of course, when asked if they would notice the gorilla in this situation, nearly everyone says they would.

Self-enhancing transmission bias

Everyone shares their successes more than their failures. This leads to a false perception of reality and inability to accurately assess situations.

Status quo bias

The tendency to prefer things to stay the same. This is similar to loss-aversion bias, where people prefer to avoid losses instead of acquiring gains.

Stereotyping

Expecting a group or person to have certain qualities without having real information about the individual.

There may be some value to stereotyping because it allows us to quickly identify strangers as friends or enemies. But people tend to overuse it.

For example, one study found that people were more likely to hire a hypothetical male candidate over a female candidate to perform a mathematical task, even when they learned that the candidates would perform equally well.

Survivorship bias

An error that comes from focusing only on surviving examples, causing us to misjudge a situation. For instance, we might think that being an entrepreneur is easy because we haven't heard of all of the entrepreneurs who have failed.

It can also cause us to assume that survivors are inordinately better than failures, without regard for the importance of luck or other factors.

Tragedy of the commons

We overuse common resources because it's not in any individual's interest to conserve them. This explains the overuse of natural resources, opportunism, and any acts of self-interest over collective interest.

Unit bias

We believe that there is an optimal unit size, or a universally-acknowledged amount of a given item that is perceived as appropriate. This explains why when served larger portions, we eat more.

Zero-risk bias

Sociologists have found that we love certainty — even if it's counterproductive.

Thus the zero-risk bias.

In general, people tend to prefer approaches that eliminate some risks completely, as opposed to approaches that reduce all risks — even though the second option would produce a greater overall decrease in risk.

Popular Right Now

Popular Keywords

Advertisement